Poultry based livelihoods of rural poor: Case of

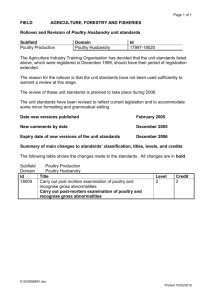

advertisement