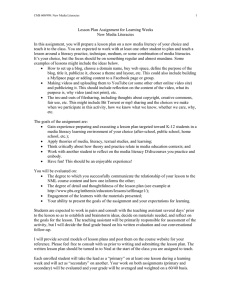

the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the Confronting

advertisement