FACTORS THAT PRESENT CHALLENGES TO HEALTHCARE STAFF DURING REVIEW OF LITERATURE

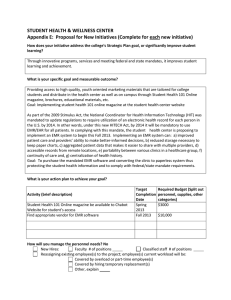

advertisement