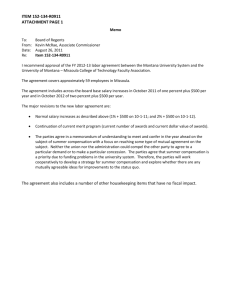

Montana | policy review

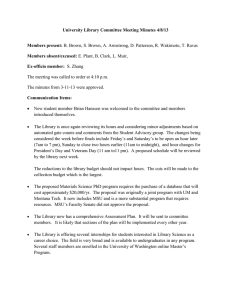

advertisement