THE IMPACT OF INCREASED NONFICTION READING ON STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT IN SCIENCE by

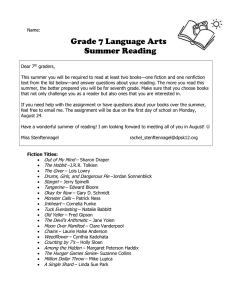

advertisement