JANUARY 2005

Pennsylvania Gaming

Unions: What Do They Mean for a Gaming Industry Employer?

The gaming industry is on the move with growth

and change. Coupled with organized labor’s

renewed commitment to organizing, these

circumstances make labor relations a critical issue

for all employers in the gaming industry.

Every employer in the gaming industry faces

numerous employment issues each and every day.

Among those are the threat or the actuality of a

union representing its employees. Each employer

in the gaming industry, including each entity that

will become licensed to operate slot machines as

part of Pennsylvania’s Racinos, is subject to the

provisions of the National Labor Relations Act (the

“Act”).

Since the Act’s application to the gaming industry

began in the mid-1960’s, numerous issues have

arisen and been resolved, while other issues remain

unsolved. This Alert will take a brief look at those

representation and bargaining issues that have

arisen in the gaming industry and at the National

Labor Relations Board (“NLRB” or the “Board”)

decisions that have framed the issues.

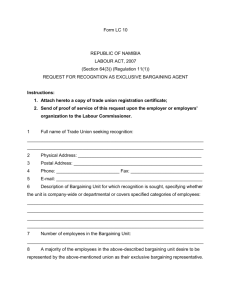

THE NATIONAL LABOR RELATIONS ACT

Employees in the gaming industry may organize

and become represented by a union. If they decide

to do so, the Act defines the rights of employees to

organize, sets forth rules governing the conduct of

an organization campaign election, and provides a

process for resolving disputes that may arise. The

Act also defines the rights of employees to bargain

collectively with their employers through

representatives of their own choosing. To ensure

that employees can freely choose their own

representatives for the purpose of collective

bargaining, or choose not to be represented, the Act

establishes a procedure by which they can exercise

their choice at a secret-ballot election conducted by

the Board.

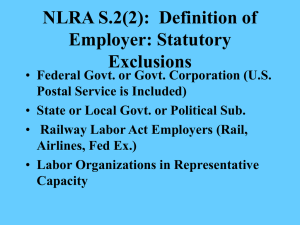

JURISDICTION

The NLRB has asserted jurisdiction over the gaming

industry for many years. It first asserted jurisdiction

over a gaming enterprise back in 1963, viewing it as

being part of a hotel operation. Hotel La Concha,

144 NLRB 754 (1963). The NLRB later asserted

jurisdiction over gaming enterprises regardless of

any hotel affiliation. El Dorado Club, 151 NLRB

579 (1965).

Like those early cases, the recent Board decision in

San Manuel Indian Bingo & Casino, 341 NLRB No.

138 (2004), will also have a big impact on gaming,

as it created a new standard for determining the

circumstances under which the Board will assert

jurisdiction over Indian owned and operated

enterprises. For the first time, the Board determined

that its jurisdiction extends to tribes and tribal

enterprises, regardless of where they are located.

The Board’s rationale for shifting its position was

the increased effect of Indian gaming on interstate

commerce and the fact that exerting jurisdiction

over such matters did not “touch exclusive rights of

self-governance in purely intramural matters.”

Of particular interest to those in the gaming industry

looking to expand into Pennsylvania is the

jurisdictional issue concerning slot machine

enterprises that are part of racetracks, i.e. “Racinos.”

The NLRB historically has not asserted jurisdiction

over the horseracing industry,1 but has begun to

assert its jurisdiction over racino-type operations

that are substantially comprised of slot machine

operations. The two key factors are: (1) what

duties does the employee primarily perform – those

related to the slot operations or those related to the

track operations; and (2) how closely integrated are

the slot and track operations? In Delaware Racing

Association, 325 NLRB 156 (1997), and Racing

Association of Central Iowa, 324 NLRB 550

(1997), the Board concluded that if the employees’

job functions relate predominately to the casino

enterprise and there was no significant functional

integration between the casino and the track, then

the casino operation did not involve the horseracing

industry and the NLRB would assert jurisdiction

over that portion of the operation.

These decisions suggest that the NLRB is likely to

assert jurisdiction over those employers operating

slot machines at Pennsylvania’s Racinos. The

question then becomes: which employees may

unionize?

HOW IS THE APPROPRIATENESS

OF A UNIT DETERMINED?

The appropriateness of a bargaining unit is

generally determined on the basis of a community

of interest of the employees involved. Those who

have the same or substantially similar interests

concerning wages, hours and working conditions

are grouped together in a bargaining unit. Other

factors that are commonly considered include:

1. Any history of collective bargaining between

management and that group of employees;

2. The desires of the employees; and

3. How the employer has structured the work force.

There is no absolutely “right” or “wrong”

bargaining unit, and, with some limitations, the unit

favored by the employees and union is given some

deference.

EXAMPLES OF BARGAINING UNITS

DEEMED APPROPRIATE

Below are summaries of recent bargaining units in

which employers and unions have held

representation elections in gaming and related

industries:

Q

Q

WHAT IS AN APPROPRIATE

BARGAINING UNIT?

When faced with representation issues, often one of

the first topics that must be addressed is what is the

appropriate bargaining unit or “unit of employees.”

A “unit of employees” is a group of two or more

employees who share a community interest and may

reasonably be grouped together for purposes of

collective bargaining. The NLRB has the

discretion, subject to certain limitations, to

determine whether a group of employees is an

appropriate bargaining unit.

Q

All casino employees in general as one unit;

Full-time and regular part-time table game

dealers (this is particularly interesting because

dealers have traditionally resisted organizational

efforts, but are common targets of unions seeking

to represent them in collective bargaining);

Cashiers – decisions vary as to whether the

appropriate cashier unit is one combined unit or

multiple cashier units;

Q

Engineers and maintenance personnel;

Q

Slot technicians and apprentices;

Q

Maintenance engineers;

Q

Q

Full-time and regular part-time roller coaster

mechanics;

Full-time and regular part-time engineers and

maintenance personnel, including ride engineers;

1 Under certain circumstances, the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board may assert jurisdiction over the horse racing operations.

2 JANUARY 2005

KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART NICHOLSON GRAHAM LLP

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Full-time and regular part-time engineering

(maintenance) personnel;

Full-time and regular part-time valet parking

attendants;

Full-time and/or regular part-time security

officers performing guard duties;

Building maintenance engineers;

Slot mechanics in the slot repair department may

be separated from other repair employees such as

maintenance;

Full-time and regular part-time receiving

attendants, lead receivers, laborers and lead

laborers; and

Maintenance engineers, painters, upholsterers,

carpenters, electricians and laborers.

THE ELECTION

Although under certain circumstances an employer

may voluntarily recognize a union that provides

evidence that it represents a majority of the

employees in an appropriate bargaining unit, the

majority of employers wish to have their employees

vote in an NLRB conducted election to determine

whether a union will represent the employees. The

details of the election process are beyond the scope

of this Alert, but if it so desires, an employer has the

right to vigorously campaign against the union.

THE BARGAINING REPRESENTATIVE

AND THE EMPLOYER

Once an appropriate unit has been recognized by

the employer or certified by the NLRB, the selected

union becomes the exclusive representative

bargaining agent for all employees in the unit.

Once a collective bargaining representative has been

designated or selected by its employees, it is illegal

for an employer to bargain with individual

employees, with a group of employees, or with

another employee representative.

Few functions for a client in the field of labor

relations have such an important and lasting effect

as negotiations with a union toward reaching a

collective bargaining agreement. The collective

bargaining agreement becomes the overriding

3 JANUARY 2005

document that governs the relationship between the

employer and its employees and the union

representing its employees for the duration of the

term of the agreement.

NEUTRALITY AGREEMENTS

One of the hottest trends in collective bargaining is

organized labor’s increased attempts to circumvent

the traditional NLRB election process and proceed

straight to recognition by the employer and

bargaining on a contract by seeking to obtain

neutrality agreements. “Neutrality agreements”

take many forms and sizes. Essentially, they require

an employer to remain neutral in the face of a union

organizing drive at one of the employer’s

unorganized facilities or departments. A typical

neutrality agreement may require the signatory

employer to not only maintain campaign neutrality

but also:

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

Q

To agree to limit communications to employees

about the union;

To extend preferential hiring rights to

unorganized facilities;

To meet with the union and discuss issues such

as appropriate units, supervisory employees, and

excluded employees;

To provide the union an early list of names and

addresses of the employees in the agreed-to unit;

To grant the union access to the facilities of the

target to distribute union literature and meet with

employees;

To recognize the union based on an authorization

card majority (or some higher percentage),

without an NLRB election;

To agree to start contract negotiations for newly

organized units within a specified time frame;

To extend coverage of the neutrality agreement

to “affiliates” of the signatory company; and

To agree not to create another entity in the same

industry without ensuring it adopts the neutrality

agreement.

The NLRB has pending before it two significant

cases examining neutrality agreements but has

KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART NICHOLSON GRAHAM LLP

recently indicated that the much anticipated rulings

in Dana Corp. and Metaldyne Corp. are not likely

to be provided until the spring of 2005. Although

the subject of neutrality agreements has thus far not

been fully examined by the NLRB, reviewing courts

have generally determined that normal neutrality

clauses, once agreed to, are enforceable in federal

court.

coupled with organized labor’s renewed

commitment to organizing, make it a harrowing

time for employers dealing with workplace issues.

One thing is likely to remain a constant, and that is

that employers will continue to need effective legal

representation when dealing with the NLRB and

organized labor to avoid the traps, intentional and

unintentional, that will be present.

If those decisions are a foreboding of how the

NLRB will decide Dana Corp. and Metaldyne

Corp., an employer who enters into a neutrality

agreement will likely see a court enforce the

employer’s commitments unless the issue implicates

the NLRB’s representation processes or violates a

statutory provision of the Act.

Hayes C. Stover

412.355.6476

hstover@klng.com

Von E. Hays

214.939.4959

vhayes@klng.com

Jacqueline Jackson-DeGarcia

CONCLUSION

717.231.5877

The gaming industry is growing and dynamic. The

changes in the industry and the modern workforce,

jjacksondegarcia@klng.com

If you have questions or would like more information about K&LNG’s Betting and Gaming Practice, please

contact one of our lawyers listed below:

Harrisburg

London

David R. Overstreet

Warren L. Phelops

717.231.4517

+44.20.7360.8129

doverstreet@klng.com

wphelops@klng.com

www

w.. k l n g . c o m

BOSTON

■

DALLAS

■

HARRISBURG

■

LONDON

■

LOS ANGELES

■

MIAMI

■

NEWARK

■

NEW YORK

■

PITTSBURGH

■

SAN FRANCISCO

■

WASHINGTON

Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP (K&LNG) has approximately 950 lawyers and represents entrepreneurs, growth and middle market companies and leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100

global corporations nationally and internationally.

K&LNG is a combination of two limited liability partnerships, each named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP, one qualified in Delaware, U.S.A. and practicing from offices in Boston, Dallas,

Harrisburg, Los Angeles, Miami, Newark, New York, Pittsburgh, San Francisco and Washington and one incorporated in England practicing from the London office.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances

without first consulting a lawyer.

Unless otherwise indicated, the lawyers are not certified by the Texas Board of Legal Specialization.

Data Protection Act 1988 - We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP seminars and with our regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you.

We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail cgregory@klng.com if you would prefer not to receive this information.

© 2005 KIRKPATRICK & LOCKHART NICHOLSON GRAHAM LLP. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.