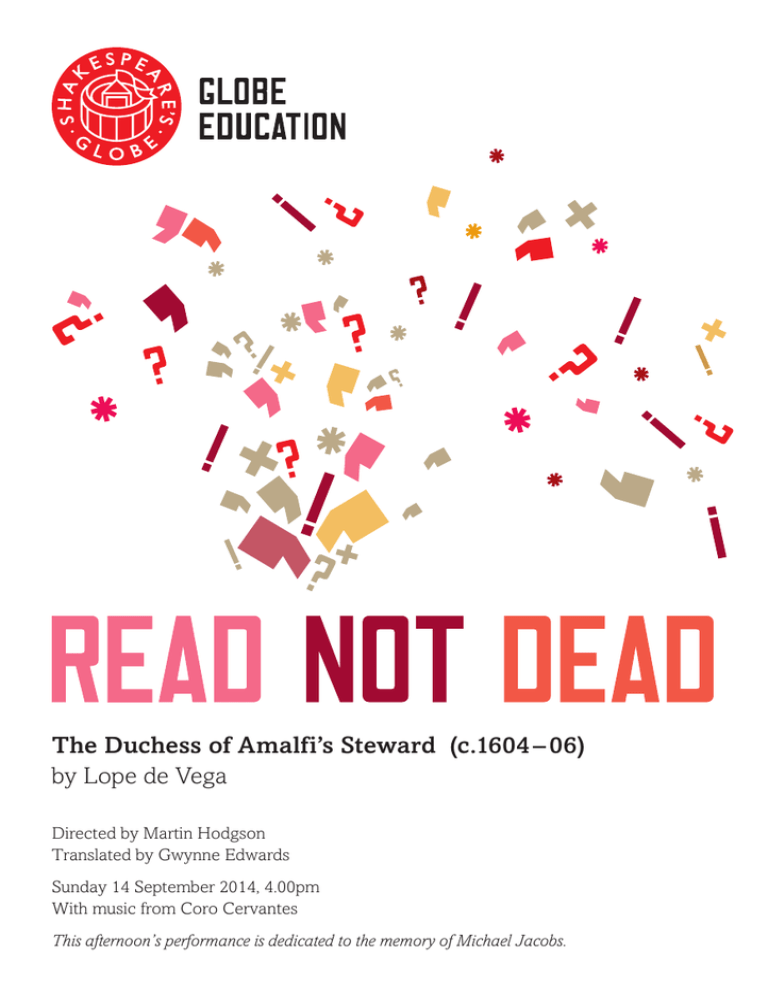

The Duchess of Amalfi’s Steward (c.1604 – 06)

advertisement

The Duchess of Amalfi’s Steward (c.1604 – 06) by Lope de Vega Directed by Martin Hodgson Translated by Gwynne Edwards Sunday 14 September 2014, 4.00pm With music from Coro Cervantes This afternoon’s performance is dedicated to the memory of Michael Jacobs. The Duchess of Amalfi’s Steward This afternoon’s staged reading and the music from Coro Cervantes are dedicated to the memory of Michael Jacobs (1952 –2014). Michael was an art historian, writer, indomitable traveller and lover of all things Spanish. He loved theatre, too, and was a great supporter of Read Not Dead. He advised us on our Shakespeare and Spain season and translated Lope de Vega’s The Innocent Child of La Guardia (published by Oberon Books) for our 1998 Shakespeare and the Jews season. Michael and I often discussed new translation projects but these always had to be postponed because of his journeys within South America and Spain. Impossible to list all of Michael’s books here but if you plan to walk The Road to Santiago De Compostela, go to Andalucia, visit Madrid, Barcelona or the Alhambra, take the relevant book by Michael with you. Even if you are not planning a visit, read his Factory of Light: The Story of My Andalucian Village – a village he adopted and which adopted him. Patrick Spottiswoode Lope de Vega’s The Duchess of Amalfi’s Steward Written by Dr Alexander Samson, University College London Lope Félix de Vega Carpio (1562 – 1635), the most prolific of Spain’s first generation of professional playwrights, enjoyed a career that began in the 1580s and spanned five decades. During this time he wrote at least 450 plays that we know of, although he and others claimed the figure reached into the thousands. His best known plays today are perhaps the tragedies penned towards the end of his career El caballero de Olmedo (The Knight of Olmedo) (c.1620) and El castigo sin venganza (Punishment without Revenge) (1631), the so-called peasant honour diptych Fuenteovejuna (c.1612 – 14) and Peribáñez y el comendador de Ocaña (c.1605 – 8), and the romantic comedies El perro del hortelano (Dog in a Manger) (1613 – 15) and La dama boba (Lady Nitwit) (1613). His version of El mayordomo de la duquesa de Amalfi was written between 1604 and 1606 and enjoys the distinction of being one of only ten works explicitly described by their author as tragedies. In his tonguein-cheek address to one of Madrid’s literary academies on his methods and theory of writing for the theatre, Lope described the Spanish ‘comedia nueva’ as a monster; like the Minotaur, the progeny of a bestial coupling of comic and tragic elements. Tragedies derived their plots from history. Perhaps one reason for using this rare epithet was the fact that the play was based of course on a true story; the death of Giovanna d’Aragón, the titular duchess, who after being widowed at nineteen had an affair with her majordomo, which they managed to conceal despite producing three children. Her disappearance after an attempted reunion with her lover never to be heard from again provided Mateo Bandello with the raw materials for his 1554 version, in his famous Novelle (Pt. 1, 26). Lope’s play drew directly on the original, neutrally-presented Italian version of the tale, which Webster may also have known, although the Englishman’s main source was almost certainly William Painter’s 1567 translation of Pierre Boaistuau and François Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1559 ) moralised French adaptation, which incorporated moral condemnation of the lascivious widow, something not developed by either Lope or Webster. Although both Wester and Lope’s plots derived from the same source their treatment of it is remarkably different. Webster’s macabre focus on machiavellian politicians, twisted sexual desire and grisly revenge see; the Duchess strangled by the end of Act 4, while Lope’s heroine is poisonned and dies beholding the severed heads of Antonio and their two children right at the end of the play. The Jacobean revenge tragedy counts the malefactors, the icy Cardinal and incestuous Ferdinand amongst its victims, whereas the fate of Lope’s villain is curtained off, with the young duke vowing to avenge his mother. Perhaps the most interesting character in Webster’s play is Bosola, the malcontented assassin, whose change of heart sees some of the most delightfully twisted Jacobean stage villains biting the dust in quick succession. Although both plays contain a scene in which the duchess is presented with the tableau of her dead husband and children, false in Webster, real in Lope, it seems fanciful to suggest that Webster might have known his Spanish counterpart’s play. What both plays do have in common is an interest in female power and social ambition. In common with his romantic comedies, much of the interest in Lope’s play resides with the character of Antonio, much more sketchily drawn by Webster, who is clearly less interested in his suffering. Critics have pointed to similarities between Lope himself and the secretary figure, Teodoro in Dog in a Manger, whose liaison with his mistress, the Countess of Belfor, results in marriage and a happy ending as opposed to tragedy. In different contexts, he explored figures whose social position is at odds with their worth and virtue, and the complications caused by desires that transgress boundaries of rank and social class, as well as race and religion. Many Spanish comedias explore the exigencies of high poisition and rank, the disjunction between the political and personal, the way that the bodies of princes are caught between their majesty and humanity. Critics of both plays have suggested that we should not be too easily dismissive of the moral failing and irresponsibility implicit in the Duchess’ clandestine marriage to a subordinate. However, both plays clearly carry the audience’s sympathies in another direction and force them to confront broader moral and political questions about the nature of social hierarchy and difference in their respective countries. What does set the two plays apart is their different dramatic languages. Webster’s pithy blank verse lends itself to concrete and colloquial speech, while Lope’s polymetric verse offers a more abstract, metaphorical literary language, of greater expressive richness but less gritty directness. Their contrasts and comparisons are a source of fascination. While El mayordomo de la duquesa de Amalfi may not be one of the phoenix of the imagination’s best plays, as Cervantes described Lope, it is a subtle and affecting piece of drama that loses nothing from being set alongside Webster’ masterpiece. CORO CERVANTES Coro Cervantes is a professional AngloSpanish choir based in London. Through its performances and recordings it aims to bring the music of Iberia and Latin America to audiences everywhere. Founded by its director Carlos Fernández Aransay under the auspices of the Instituto Cervantes in London, Coro Cervantes made its first public appearance at the Spanish Embassy in 1996 and has performed in Spain, Mexico and Russia in addition to renowned London venues. music Today’s performers Around Lope de Vega (1562–1635) Amaia Azcona Cildoz Soprano Lope used to employ songs and music in his works as intervals or within the plot itself. Sometimes writing a contrafactum for a determined, often popular, piece of music and for others inserting well known texts. Debra Skeen Alto Jorge Carrasco Juarez Tenor Jagoba Fadrique Bass Frances Kelly Baroque Harp Pedro Alcácer Doria Vihuela All of the pieces that we are performing are contemporary to Lope, from late 16th Century to early 17th. 1. Si tus penas no pruebo Francisco Guerrero (1528-1599) 4. Entre dos álamos verdes Juan Blas de Castro (c.1561-1631) Besides being a dramatist and a poet, Lope was a clergyman. He wrote the religious Soliloquios amorosos de un alma a Dios. For the beginning of Soliloquio VII he adapts a spiritual villanesca from Guerrero himself. Part of Las fortunas de Diana. Blas de Castro became Lope’s best friend when they met at the court of the Duke of Alba in Salamanca. He put several of Lope’s poems to music. 2. Esto es amor, quien lo probó lo sabe Anonymous (s.XVII) 5. Vida bona, vida bona Juan Arañés (died c.1649) Sonnet 126 is without doubt one of Lope’s most beautiful poems. 3. Mira, Nero de Tarpeya Francisco Fernández Palero (c.1533-1597) In Roma Abrasada Lope inserts this old romance that already appeared a Century before in La Celestina by Fernando de Rojas. Contrafactum of A la vida bona inspired by Cervantes’ La ilustre fregona and appearing in El amante agradecido. One of the most well-known Spanish music pieces from that period. Shakespeare at 450 forthcoming events Professor Lisa Jardine (University College London) Thursday 18 September Lisa Jardine is Professor of Renaissance Studies at University College and Director of the Centre for Humanities Interdisciplinary Research Projects. Her books include Still Harping on Daughters: Women and Drama in the Age of Shakespeare, Reading Shakespeare Historically, Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance and Global Interests: Renaissance Art Between East and West (with Jerry Brotton) and biographies of Erasmus, Christopher Wren, Francis Bacon and Robert Hooke. Professor Stanley Wells (The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust) Thursday 2 October Stanley Wells is a Life Trustee and Former Chairman of The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and Emeritus Professor of Shakespeare Studies of the University of Birmingham. He is a Trustee of the Rose Theatre, and a former Trustee of Shakespeare’s Globe. He is co-editor of The Oxford Complete Works and General Editor of the Oxford Shakespeare. His books include Re-Editing Shakespeare for the Modern Reader, Shakespeare: The Poet and his Plays, Shakespeare For All Time, Shakespeare & Co and Shakespeare Sex and Love. TIME 7.00pm VENUE Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, Shakespeare’s Globe TICKETS £15 (£10 FoSG/cons/ students) #ReadNotDead thank you Globe Education would like to thank: Dr Alexander Samson (UCL), Maggie & David Williams and Dr Will Tosh; the Box Office, the Communications Department and the Theatre Department at Shakespeare’s Globe for their help with this reading. Our heartfelt thanks go to Jean Jayer and to the Stewards who have donated their time to make this event possible. Globe Education is very grateful to Nick Hutchison and the actors who have graciously given their time today.