Utilization of Animal-borne Video Cameras in Determining the

advertisement

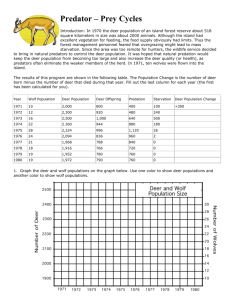

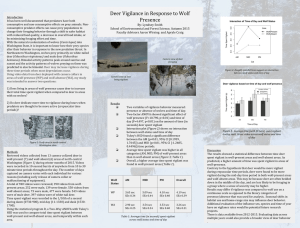

Utilization of Animal-borne Video Cameras in Determining the Non-Consumptive Effects of Wolves on White-tailed Deer in Eastern WA Kyla Caddey, Graeme Riggins School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Fall 2013 Introduction Discussion Many studies have solely focused on the consumptive effects of predators on prey populations (actual consumption of prey animals) without addressing less obvious non-consumptive predator effects (intimidation factors). Without these risk effects added into the equation, full impacts of predators on prey will not be understood and addressed, leading to erroneous management decisions. For our capstone research, we proposed to study the non-consumptive risk effects of wolves (Canis lupus) on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in Washington as a means to determine how this prey species responds to the return of a predator that historically resided in the area. Although it was not deemed significant in the analysis, there seems to be a trend of increased vigilance in wolf present areas compared to the wolf absent areas. The inability to present a significant result is likely due to the small sample size available. With a greater sample size, this might prove different. More research should be conducted on this subject because if this trend is confirmed, the data could act as a basis in for further studies to determine if there are similar nonconsumptive behavioral responses in other deer species (e.g. mule). Once more data are available, state management agencies such as Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife could more accurately predict impacts of predator removal or restoration proposals because there will be a clearer understanding of the full impacts of predators on prey (consumptive and non-consumptive effects). •Question: How does the presence of wolves affect the vigilance of white-tailed deer? (Definition of vigilance: the action or state of keeping careful watch for possible danger) •Null hypothesis: Wolf presence has no effect on the proportion of time spent vigilant for white-tailed deer. •Alternative: Wolf presence will increase the proportion of time spent vigilant for white-tailed deer. Figure 2: A vigilant, male white-tailed deer Results With the F critical value (7.71) exceeding the observed F value (2.737), we did not reject the null hypothesis that wolf presence has no effect on the proportion of time spent vigilant for white-tailed deer. Methods Site: Four study locations in Okanogan and Ferry Counties, E. WA: Two with wolves present and two with wolves absent. Figure 3: Raw proportions of vigilance out of total foraging time recorded for each deer. Data Retrieval: Camera/GPS collars were attached to mule and white-tailed deer (in winter), of which only whitetailed had sufficient numbers for analysis (3 or more in wolf present and absent sites). Video footage was examined for the necessary behavioral data (vigilance and foraging) for analysis. Deer were considered vigilant if they were actively foregoing forage to be alert. Figure 4: Predators can have effects other than consumption on their prey. Acknowledgements Thank you to Aaron Wirsing for his guidance and encouragement, to Justin Dellinger for supplying the data for analysis, and to all those who helped analyze the many days worth of video footage. Figure 4: Square root ArcSin transformed vigilance proportions show no statistical difference, due to large standard deviation. Figure 1: The collars used were similar in design to these. Statistical Analysis: We performed an ANOVA on the proportion of time deer spent vigilant out of total foraging duration in areas with and without recorded wolf presence. The data were squareroot ArcSin transformed before analysis, because of their proportional nature.