2010 tribal public health profile

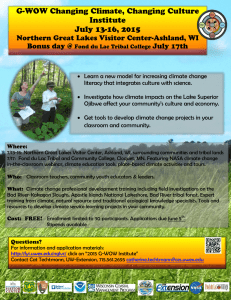

advertisement