Advanced Noninvasive Geophysical Monitoring Techniques

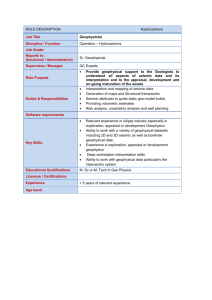

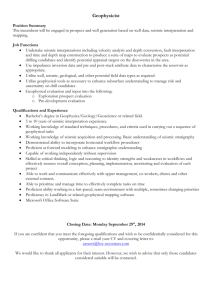

advertisement