Document 13390188

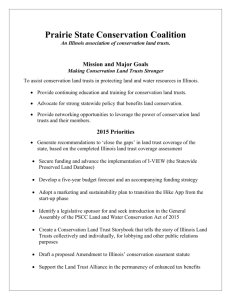

advertisement