corpcounsel.com | June 16, 2015

6 Critical Issues When Responding to

Government Subpoenas

From the Experts

Shanda N. Hastings and Noam A. Kutler

Government investigations take a variety

of shapes and forms, but nearly all will

include requests for the production of

documents. Here are six critical issues that

may result in significant problems for a bank

or financial institution if overlooked before

materials are produced—and some related

issues to consider after production is done.

1. Time Limitations on Challenging

the Scope of a Government Subpoena

Subpoenas for documents in government investigations are often quite broad.

Some agencies are not very flexible in

reducing or narrowing the scope. It is

important to recognize that the statutes

that authorize government agencies to

issue subpoenas often provide a narrow

time period for the recipient to challenge

the scope of the subpoena in court. For

example, the statute applicable to many

subpoenas issued by the U.S. Department

of Justice (18 U.S.C. § 1968(h)), provides

a party with just 20 days after service, or

the deadline of the subpoena production,

whichever is shorter.

If the subpoena recipient wants to

negotiate the scope or the timing, it is

critical to reach out to the government

agency that issued the subpoena as

soon as possible. Otherwise, the entity

that received the subpoena could lose

its ability to challenge the subpoena

in court, should the negotiations be

unsuccessful. It also may be necessary

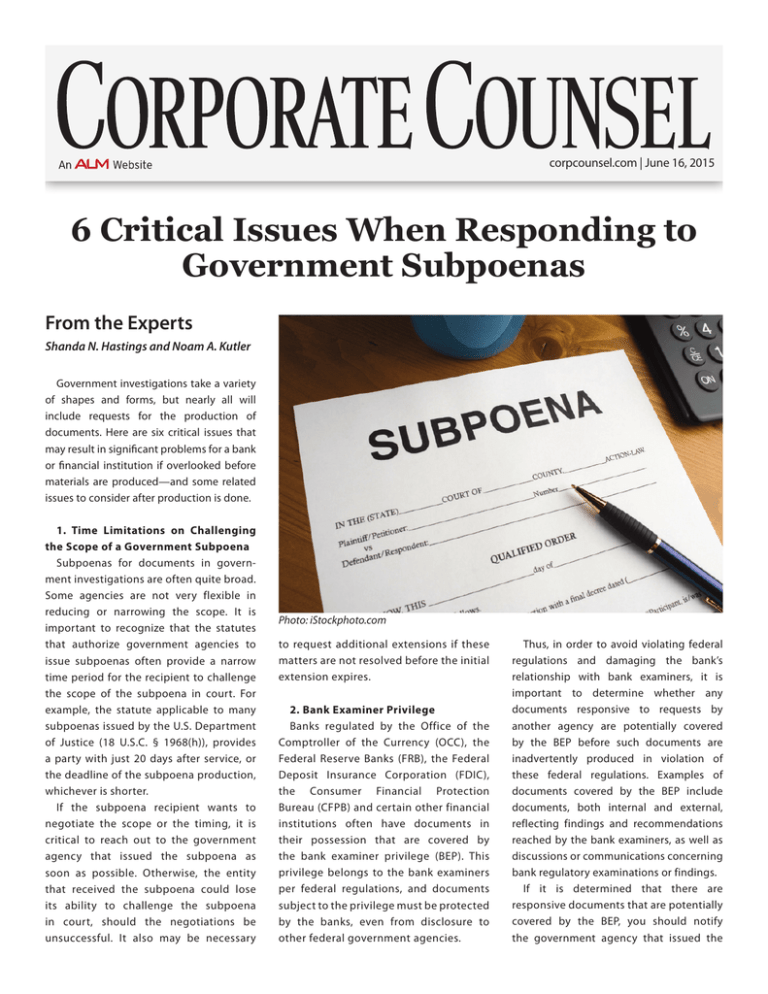

Photo: iStockphoto.com

to request additional extensions if these

matters are not resolved before the initial

extension expires.

2. Bank Examiner Privilege

Banks regulated by the Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the

Federal Reserve Banks (FRB), the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC),

the Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau (CFPB) and certain other financial

institutions often have documents in

their possession that are covered by

the bank examiner privilege (BEP). This

privilege belongs to the bank examiners

per federal regulations, and documents

subject to the privilege must be protected

by the banks, even from disclosure to

other federal government agencies.

Thus, in order to avoid violating federal

regulations and damaging the bank’s

relationship with bank examiners, it is

important to determine whether any

documents responsive to requests by

another agency are potentially covered

by the BEP before such documents are

inadvertently produced in violation of

these federal regulations. Examples of

documents covered by the BEP include

documents, both internal and external,

reflecting findings and recommendations

reached by the bank examiners, as well as

discussions or communications concerning

bank regulatory examinations or findings.

If it is determined that there are

responsive documents that are potentially

covered by the BEP, you should notify

the government agency that issued the

June 16, 2015

subpoena and inquire if it is still demanding

production of those documents after

learning that the documents contain

protected material. If the BEP documents

cannot be excluded from the subpoena

through negotiation, then you must notify

the relevant bank examiner that such

documents have been requested. In some

cases, the government agency requesting

the materials may accept a production

from which the BEP material has been

logged and redacted or withheld. If so,

it is prudent to send the log to the bank

examiners before production and seek

their permission to produce the log and

any redacted materials. If the government

agency requesting the documents insists

on receiving the BEP materials, bank

examiners must be provided with an

opportunity to decide whether they will

assert the privilege over those documents.

3. The Bank Secrecy Act

Similarly, the U.S. Department of Treasury

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network

(FinCEN) has set forth stringent limitations

on the production of documents covered

by the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), including

documents related to Suspicious Activity

Reports (SARs), Currency Transaction

Reports (CTRs) and other reports.

In circumstances where the federal

regulations allow for the production of

BSA materials to another government

agency, the documents containing BSA

information must be segregated from

other materials produced in response to a

request from a government agency (e.g.,

produced on a separate disc or hard drive),

and the documents and the separate disc

or hard drive must be clearly labeled as

containing BSA confidential information.

4. The Right to Financial Privacy Act

The Right to Financial Privacy Act (RFPA)

prevents financial institutions and their

employees and agents from providing

any agency or department of the federal

government with access to the information

contained in the financial records of certain

of its customers—unless the government

agency seeking such records certifies

in writing to the financial institution

that it has complied with the applicable

provisions of RFPA. Failure to do so could

result in liability to the customer(s) by the

financial institution and its employees and

agents. The term “financial record” has

been interpreted broadly by the courts

and includes obvious financial records,

such as loan files and account statements,

but may cover company records that list

information related to customer financial

records, such as loan lists or loan tapes.

Before producing documents to the

federal government, it is important to

analyze whether the entity producing

the documents is covered by RFPA and

whether the production will include

covered customer financial records. If so,

it is important to get the required RFPA

certification from the government agency

first—unless the government agency

proactively included a certification with

its subpoena.

5. Hidden Data

In today’s world of voluminous

e-discovery, reviewers can inadvertently

overlook the fact that hidden data, such

as tracked changes, hidden Excel rows and

worksheets, PowerPoint notes, and notes

in Outlook calendar invites are contained

in documents. The hidden data may

contain privileged or sensitive information

and can lead to the inadvertent production

of privileged material or cause reviewers

to fail to identify key information.

In many cases, the vendor that maintains

the document review database can include

fields in the review database that will alert

reviewers to the existence of such hidden

data so they can open the document in

native format and examine it. It is crucial to

highlight in training materials and training

sessions the importance of reviewing

hidden data in documents that may be

responsive to government agency requests.

6. Issues that Can Arise Months and

Years After the Subpoena Response

You should continue to monitor the

government agency’s investigation even

after the bank or financial institution is

no longer involved in the investigation.

In some instances, documents produced

to the government may be used

during related third-party litigation as

exhibits and, as a result, may become

publicly available. In such cases, the

protections sought under the Freedom of

Information Act (FOIA) may not ensure the

confidentiality of the documents.

Documents

produced

to

the

government may include highly sensitive

business documents and customer or

employee data that could cause business

and reputational harm to the banks and

financial institutions, if made public. It is

important to be vigilant and ensure that

sensitive customer and employee data

is being protected appropriately in such

litigation and to seek a protective order,

when appropriate, to ensure the continued

confidentiality of sensitive documents

provided in response to investigative

requests by a government agency.

Shanda N. Hastings, a partner in K&L

Gates’ government enforcement practice,

represents banks and other financial

institutions, public and private companies,

corporate officers and directors, compliance

personnel and accountants in enforcement

proceedings and examinations before

federal and state government agencies and

in related litigation. She also specializes in

internal investigations. Noam A. Kutler, an

associate in the firm’s Washington, D.C.,

office, focuses his practice primarily on

civil litigation, including false claims act

litigation and representing clients before

enforcement agencies.

Reprinted with permission from the June 16, 2015 edition of

CORPORATE COUNSEL © 2015 ALM Media Properties, LLC.

This article appears online only. All rights reserved. Further

duplication without permission is prohibited. For information,

contact 877-257-3382 or reprints@alm.com. # 016-06-15-10