United States v

advertisement

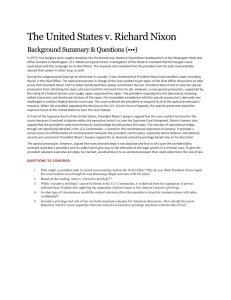

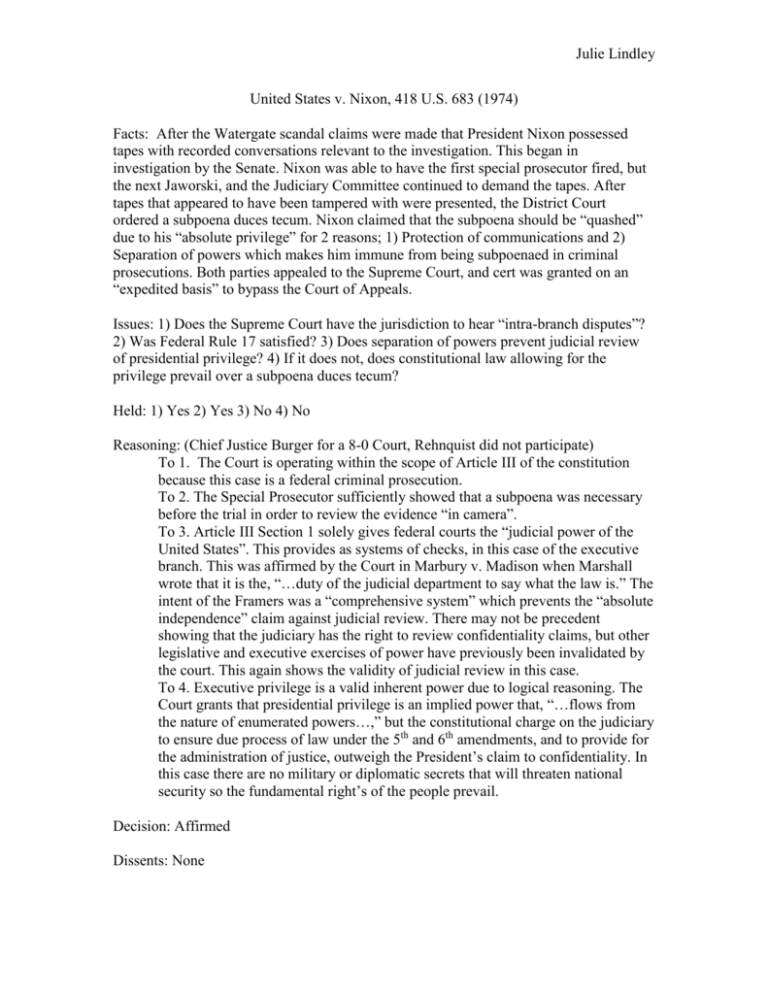

Julie Lindley United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974) Facts: After the Watergate scandal claims were made that President Nixon possessed tapes with recorded conversations relevant to the investigation. This began in investigation by the Senate. Nixon was able to have the first special prosecutor fired, but the next Jaworski, and the Judiciary Committee continued to demand the tapes. After tapes that appeared to have been tampered with were presented, the District Court ordered a subpoena duces tecum. Nixon claimed that the subpoena should be “quashed” due to his “absolute privilege” for 2 reasons; 1) Protection of communications and 2) Separation of powers which makes him immune from being subpoenaed in criminal prosecutions. Both parties appealed to the Supreme Court, and cert was granted on an “expedited basis” to bypass the Court of Appeals. Issues: 1) Does the Supreme Court have the jurisdiction to hear “intra-branch disputes”? 2) Was Federal Rule 17 satisfied? 3) Does separation of powers prevent judicial review of presidential privilege? 4) If it does not, does constitutional law allowing for the privilege prevail over a subpoena duces tecum? Held: 1) Yes 2) Yes 3) No 4) No Reasoning: (Chief Justice Burger for a 8-0 Court, Rehnquist did not participate) To 1. The Court is operating within the scope of Article III of the constitution because this case is a federal criminal prosecution. To 2. The Special Prosecutor sufficiently showed that a subpoena was necessary before the trial in order to review the evidence “in camera”. To 3. Article III Section 1 solely gives federal courts the “judicial power of the United States”. This provides as systems of checks, in this case of the executive branch. This was affirmed by the Court in Marbury v. Madison when Marshall wrote that it is the, “…duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” The intent of the Framers was a “comprehensive system” which prevents the “absolute independence” claim against judicial review. There may not be precedent showing that the judiciary has the right to review confidentiality claims, but other legislative and executive exercises of power have previously been invalidated by the court. This again shows the validity of judicial review in this case. To 4. Executive privilege is a valid inherent power due to logical reasoning. The Court grants that presidential privilege is an implied power that, “…flows from the nature of enumerated powers…,” but the constitutional charge on the judiciary to ensure due process of law under the 5th and 6th amendments, and to provide for the administration of justice, outweigh the President’s claim to confidentiality. In this case there are no military or diplomatic secrets that will threaten national security so the fundamental right’s of the people prevail. Decision: Affirmed Dissents: None Significance: Burger reaffirmed the power of judicial review by first establishing the constitutional power of the court, and then by relying on the precedent of Marbury. The Court also limited the inherent power of the president to exercise executive privilege of confidentiality. The administration of justice was deemed more important, and consequently the ruling limited the power of the president by placing a check on an inherent power.