PLACING WARDAK AMONG PASHTO VARIETIES by Dennis Walter Coyle

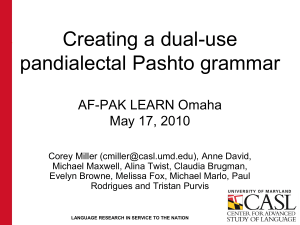

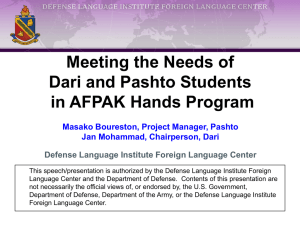

advertisement