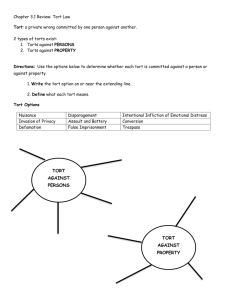

The Risks of and Reactions to Underdeterrence in Torts

advertisement