Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

Managing High Potential Employees: A Case of Employers in

Malaysia

Nurita Juhdi, Fatimah Pa‟wan and Ram Milah

The main objective of the survey was to determine high potential

(HIPO) employee development practices in Malaysia. Two hundred and thirty seven establishments from various industries participated in the survey. They were from diverse industries such as automotive, education, plantation, bank ing, financial services and insurance. The findings indicated that employers put highest emphasis on employees who were customer service oriented and able to create high performing teams. In terms of methods used to identify HIPOs in organizations, the most common method was performance appraisal by the immediate superior and the least common method was nomination method. Two most common methods to develop HIPOs were job enlargement and executive development programs and the least used was executive

MBA program.

Field of research: Management

1. Introduction

HIPOs are the organization‟s top performers in their current jobs and have the potential to move up to higher positions and more challenging responsibilities. The

Conference Board‟s 2010 study on CEO indicated 3 major challenges: business growth, talent and innovation and thus, the war for talent is on (Barrington, 2010).

Research conducted in 2009 by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) indicated that innovation is the single most important predictor of future growth (EIU, 2009).

Innovation is all ab out producing something new that requires „out of the box‟ mindset. It enables organizations to grow and be competitive. Organizations depend on human capital to anticipate and steer changes. This is where the value of human capital outweigh the other types of capital for growth. Global Talent

Index (GTI) 2011-2015 produced by Heidrick & Struggles and the EIU further cited that Malaysia is at number 36 out of 60 countries surveyed (EIU, 2011). Being at

__________________

Nurita Juhdi, Assistant professor, Department of Business Administration,Kulliyy ah of Economics and Management Sciences, International Islamic University Malaysia, P.O. BOX 10, 50728 Kuala

Lumpur, Malaysia. Email: nurita@iium.edu.my. Tel: 03-61964743, Fax: 03-61964644

Fatimah Pa‟wan and Ram Milah, Senior lecturers, Faculty of Busines s Administration, UNITAR

International University Malaysia, Block C, Leisure Commerce Square, No.09, Jalan PJS 08/09,

46150 Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia, Email: fatimahp@unitar.my and rammilah@unitar.my.

Tel: 03-76277270, 03-76277255, Fax: 03-76277472

1

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1 the 36 th

place indicated that Malaysia is at an average position in producing talents and it also showed that Malaysia has to improve its ability to provide the conditions needed to develop talents. Nonetheless, it should be noted that this is not the only issue in the development of future leaders, because what is more important is whether employers are able to retain these talents. An online article by The Edge

Malaysia (Dec 21 –27, 2009) indicated a survey done by Hewitt reported that the turnover rate in Malaysia increased from 9.3 percent to 10.1 percent. The highest turnover rate was in financial services (18.3 percent), high-tech/IT industry (20 percent) and the lowest turnover rate was seen in the chemicals industry at

6.3%. This has triggered the needs to conduct a study that examine how organizations in Malaysia identify, develop and manage their HIPOs.

2. Literature Review

HIPO employees, as defined by Schumacher (2009), are employees who produce excellent work performance consistently. The author also noted that HIPOs are not similar to high performers because the latter are employees who produce immediate results but not necessarily possess aspirations or engagement. HIPOs are the people who have the potential to assume higher positions in the future and they normally score well on various leadership assessment criteria (Schumacher,

2009). Derr (1987) noted that normally HIPOs are general managers who have the possibility of climbing up the corporate ladder by certain time and HIPOs must eventually ready to become heads by the age of forty.

2.1 HIPO Characteristics

Given dynamic business environment, emergence of new markets and stiff competition among employers in getting the best employees, the need to have

HIPOs who can become the successors for the present management people is pertinent. If the management fails prepare its executives for future high positions in the organizations, they are unlikely to be able to sustain their competitiveness and positions in the industry. Therefore, HIPOs must be identified, developed and managed well. Nonetheless, the identification of HIPOs must first be preceded with determining the competencies that employees must have to be called HIPOs, in other words, HIPOs competencies must be clearly defined and the determination of such competencies must be in line with t he organizations‟ missions and goals. There have been many studies that sought to define HIPOs in terms of their competencies. Schumacher (2009) listed several characteristics such as quick learners, risk takers, consistent high performers, have growth potentials and positive energy. Gritzmacher (1989) outlined nine characteristics that include independent, committed, time conscious and have high need for continuous improvement and creativity. Snipes (2005) established 13 attributes that are most sought after by organizations. That includes the ability to maintain a high level of competence in technical or functional discipline, to consistently produce results above expectations and to be bias for action.

2

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

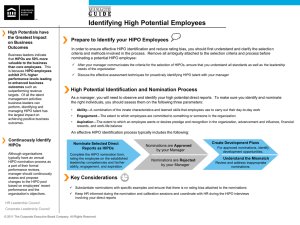

2.2 Identifying HIPOs

The common ways used to identify HIPOs are assessment centers, performance appraisal, 360 degree feedback system and conducting psychological tests to assess communication skills, personality, interpersonal skills and decision making style (Noe, 2008). Derr (1987) reported that many American companies use assessment centers along with other systematic programs in identifying HIPOs but the case is different with those in Europe that rarely used assessment centers.

Further, he indicates that the more common system used in Europe is by nomination of HIPOs by managers to the top management, recruiting new hires from reputable universities, hiring experienced managers from other companies and conducting extensive psychological tests before recruiting.

It was reported by Ashton and Morton (2005) that Reuters used individual assessment as one of its approaches in managing talent. One may question the reliability of self-assessment as a means to identify potential because the person has the tendency to overrate himself. Evidence from prior studies (such as

Church, 1997; Derr, Jones and Toomey, 1988) indicated consistent positive relationship between self-rated competence and ratings done by others on leadership, interpersonal and communication skills. Such findings also implied that when an individual possesses the potential and consistently performs better than others, he also would perceive that he has the traits or skills pertinent to be leaders. Further, Schumacher (2009) noted that besides the common practices in identifying HIPOs, other tools can also be used such as reviewing the individual resumes (that include the career history, skills and developmental needs) and one-to-one interview to assess accomplishment, mistake and failures.

2.3 Developing HIPOs

Formal education programs like executive MBA programs, seminars and in-house courses are normally used to provide employees with job specific skills (Stewart,

1991). Formal education is commonly used by most organizations including established giant companies like Motorola, IBM, General Electric (GE) and Dow

(Noe, 2008). One cannot deny the fact that formal education is still relevant because the employees who participated in the program reported that they learn to widen their perspectives on business issues, problem solving and decision making (Hollenbeck, 1991). MAA, a large insurance company in Malaysia, used extensive training programs in its effort to manage and develop its managers and high potential executives (Law, 2008). However, according to Peters and Smith

(1996), the formal education program has to be coupled with job experience that gives the HIPOs opportunities to feel and experience the challenges. This is further supported by the “70/20/10” characterization of Lombardo and Eichinger

(2000). They highly recommended that a development program should have 10 percent formal training, 20 percent component of coaching and mentoring and the biggest part should be hands-on. Hands-on experience can be taught to HIPOs by

3

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1 giving them opportunities to experience real work life challenges such as job rotation, job enlargement and assignment of special projects (Noe, 2008).

Another common method used is action learning. According to Peters and Smith

(1996), action learning is vital because it gives the “fast-trackers” chance to experience business challenges. It was further supported by Noe (2008) who posited that action learning is able to maximize learning and increase training transfer because it involves dealing with real problems faced in the organizations and making recommendations to senior managements. Fojt et al. (2008) recommended that for action learning to be more successful, mentors or coaches should be assigned. In earlier research by Lankua and Scandura (2002), it was suggested that employees who work under the guidance of mentors are likely to exhibit favorable work outcomes such as greater promotions and personal learning. Nonetheless, Groves (2007) cautioned that the success of mentoring relationship hinges upon the program management and quality of the relationship.

Based on the previous discussion, the following research objectives led the study:

1. to ascertain the key competencies used by organizations in identifying

HIPOs;

2. to examine common practices used to identify HIPOs and;

3. to identify common programs used to develop HIPOs.

3.

Data Collection And Research Instruments

The sample participants for the survey were selected based on convenient sampling. The respondents were company CEOs, HR managers and line managers from various industries. The data was collected by distributing the survey forms to the potential respondents. Major items used were adapted from previous studies mainly from Derr (1987), Noe (2008) and Pepermans et al.

(2003). These studies provided the theoretical perspective of HIPO development issues and based on the review on these studies, relevant items were identified and organized into several sections. Items used to measure HIPO competencies were self-developed by the researchers based on studies done by Schumacher

(2009), Gritzmacher (1989) and Snipes (2005). The other sections in the survey form sought to gather information on common practices used in identifying the

HIPOs. Some items included in this section were performance appraisal by immediate superiors, subordinates, peers and clients and assessment centers.

This section was followed by a section on common practices used in developing

HIPOs that included items like in-house seminars, executive development programs, rotation, job enlargement and assignment to special projects. All the items were measured using 5-point likert scale.

The final section was on demographic profile of the company such as number of employees, type of organization and type of industry. In order to get appropriate

4

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

The respondents were approached personally and asked to fill in the survey forms. To facilitate data collection, an online survey facility was also employed.

The respondents were given alternative options to return back their responses through regular mails, emails or online survey facility. Almost two hundred and sixty responses were generated but only 237 responses were usable for analysis.

Most organizations that were approached refused to participate despite all the follow-up effort to keep in touch.

4. Demographic Analysis

Two hundred and thirty seven establishments which participated in the study were from diverse industries such as automotive, education, plantation, banking, financial services and insurance. Sixteen percent were from banking, financial services and insurance and 11.8 percent were from public services and statutory bodies. The other industries that participated were like education, hotel and restaurant, retail and wholesale, automotive, consumer products and shipping. Out of 237 respondents, 78 percent were local establishments. Over one-third (37.6 percent) of respondents were from large establishments with more than 500 employees. 21.9 percent in medium size establishments (101 to 500 employees) and the majority respondents (40.5 percent) were in small establishments. Table 1 showed the detail characteristics of the respondents.

Table 1

Dem ographic Analyses of the Respondents (n=237)

Frequency Percentage (%)

Industry type:

Automotive

Banking, financial services and insurance

Conglomerate

Construction

Consumer products

Education

Healthcare and pharmaceuticals

High tech/IT

Hotel & Restaurant

Plantations

Property and real estate

Public services and statutory bodies

Retails and w holesale

Shared services

Shipping/logistics

Publishing

Quarrying/mining

Forestry

Type of organization:

Domestic/local

Multinational corporation

Size of establishment:

Small (1to 100 employees)

Medium (101 to 500 employees)

Large (more than 500 employees)

186

51

96

52

89

7

28

13

2

8

25

6

6

16

6

20

13

6

7

38

3

14

14

78

22

40.5

21.9

37.6

3.0

11.8

5.5

.8

3.4

10.5

2.5

2.5

3.0

16

1.3

5.9

5.9

6.8

2.5

8.4

5.5

2.5

5

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

5. Results

5.1 Objective 1: To Ascertain Key Competencies Used by

Organizations in Identifying HIPOs

As shown in Table 2, the survey showed that the most important characteristics used in HIPO identification were strong inclination towards customer services

(internal and external) (mean 4.27, SD 0.74), ability to create high performing teams (mean 4.26, SD 0.71) and initiative to develop self to achieve higher performance (mean 4.20, SD 0.76). The least important characteristics were being proactive and bias for action (mean 3.60, SD 0.92) and ability to take risks under uncertainty (mean 3.78, SD 0.71). All the items were analyzed using principal components with an orthogonal (varimax) rotation. Besides relying on visual observation of the scree plot in deciding on the number of factors to be extracted, latent roots criterion (eigenvalues greater than 1) was also used.

Eighteen items in the section that asked on characteristics used to identify HIPOs were analyzed using principal components analysis (PCA) and three components were extracted which explained 52.49 percent of the total variance. The Bartlett test of sphericity is significant and that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy is 0.917 which was far greater than 0.6. The output of the factor analysis is as indicated in Table 2. Factor 1 consisted seven items which reflected results oriented character with cronbach‟s alpha .836. Factor 2 consisted of four items that signified interpersonal competence with cronbach‟s alpha .783.

Factor 3 contained four items that portrayed technical competence/flexibility with cronbach‟s alpha .643.

Table 2: Statistics and principal component loadings of HIPO types of competence

Mean SD Factor 1: resultoriented character

4.09 .79 .774

Factor 2: interpersonal competence

Factor 3: technical competen ce/ flexibility

Sets and attains specific and challenging goals for self and team

Explores and develops own competence as preparation for greater responsibilities in the future

Creates high performing team and leverages on team capabilities to produce greater results

Shows ability to translate the organizational/departmental mission and goals into meaningful and measurable action plans for

4.07 .76 .751

4.27 .71 .636

4.15 .77 .593

6

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1 subordinates

Manages changes effectively and motivate others to do the same

Consistently produces tangible and measurable results above expectations

Shows tendency towards being inquisitive to solve problem

Displays strong inclination towards excellent customerservice, both internally and externally

Displays understanding of ethics, morals, values and culture that would affect work environment, and find the most suitable solution

Deals with conflict effectively; encourage others to come

4.01

4.04

4.00

4.27

4.10

3.97

.77

.77

.71

.74

.81

.74

.590

.579

.535 together and reconcile differences

Communicates effectively in order to develop relationship, manages conflict and works across differences

Shows ability to determine and adopt the appropriate leadership style for different situation

Delivers an impactful business presentation that is able to convince people

Evaluates situations and consequences critically before making decision

Proactive and bias for action

Shows ability to calculate and take

4.19

3.91

3.96

3.97

.82

.78

.86

.73

3.61 .92

3.78 .71 risk under condition of uncertainty

Displays high level of technical/functional competence that commands respect from others in the same field

Takes initiative to develop ownself to achieve higher performance

3.98

4.20

Eigenvalues

Percentage explained variance

Cronbach‟s alpha

Note: Only loadings ≥ .50 were included

.75

.76

6.699

37.215

.836

.780

.776

.675

.633

1.456

8.091

.783

.783

.642

.578

.531

1.293

7.182

.643

7

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

5.2 Objective 2: To Examine Practices Used to Identify HIPOs

Performance appraisal by immediate superior was indicated as the most common way to identify HIPOs in organizations (mean 4.18, SD 0.88). The other practices were quite uncommonly used and the means for the other practices ranged from

3.62 (one-to-one interview, SD 1.1) to 2.69 (nomination system, SD 1.24; i.e. the least commonly used). This showed that performance appraisals conducted in organization are still mainly done by the bosses and not by peers, subordinates or customers. PCA was used to reduce the items into three components after varimax rotation (explaining 67.19 percent of the variance, Bartlett test of sphericity is 0.00, KMO measure of sampling adequacy is 0.853). As portrayed in

Table 3, Factor 1 was labeled assessment that contained five items with cronbach‟s alpha .808. Factor 2 consisted of three items that reflected performance appraisal with cronbach‟s alpha .836. The third factor only had one item and thus it was dropped from further analysis.

Table 3: Statistics and principal component loadings of practices to identify

HIPOs

Mean SD

1.36

Factor 1: assessmen t

.814

Factor 2: performanc e appraisal

Factor 3: performance appraisal by superior

Assessment managed consultants

Assessment by centers: internal centers: managed consultants by external

Self-assessment (attitude test, personality test, etc)

Nomination system

One-to-one interview (assess achievement, weaknesses,

2.96

2.71

3.33

2.69

3.62 failure)

Performance appraisal by customers/clients

Performance appraisal by peers

Performance appraisal by subordinates

360 degree appraisal

2.98

2.87

2.97

2.82

Performance appraisal by immediate superior

4.18

Percentage variance explained

Note: Only loadings ≥ .50 were included

1.38

1.23

1.24

1.13

1.29

1.23

1.26

1.41

.87

.805

.684

.658

.529

44.439

.883

.877

.720

12.585

.881

10.169

8

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

5.3 Objective 3: To Identify Programs Used to Develop HIPOs

The survey revealed that none of the programs listed in the survey form was rated

4 and above. The highest mean was on job enlargement (mean 3.72, SD 0.89) followed by executive development program (mean 3.64, SD 1.07) and mentoring/coaching (mean 3.62, SD 1.11). The least common one was executive

MBA programs (mean 2.69, SD 1.25).

PCA on items in the section that asked on programs to develop HIPOs resulted in two factors (explaining 58.78 percent of the variance, Bartlett test of sphericity is

0.00, KMO measure of sampling adequacy is 0.831). Table 4 indicated Factor 1 contained five items that portrayed job experience with cronbach‟s alpha .794.

Factor 2 was named formal development programs contained three items with cronbach‟s alpha .70.

Table 4: Statistics and principal component loadings of programs to develop

HIPOs

Mean SD Factor 1: job experience

Factor 2: formal development programs

Transfers, downward and upward movements

Eigenvalues

Percentage explained variance

Cronbach‟s alpha

Note: Only loadings ≥ .50 were included

3.39 1.02 .748

Job enlargement (adding more responsibilities/functions, taking charge in a new project)

Job rotation (rotating HIPOs to different job assignments/posts/functions)

Assignment to special project

Mentoring/coaching (assigning

HIPOs to certain key people)

In-house seminars

3.72 .89

3.57 1.16

Executive development program 3.64 1.07

Executive MBA programs 2.69 1.25

.742

3.41 1.06 .722

3.54 1.08 .670

3.62 1.11 .522

3.656

45.703

.794

.856

.810

.543

1.046

13.080

.700

9

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

6. Discussion on Findings

The findings indicated that employers put highest emphasis on employees who were customer service oriented and able to create high performing teams . As indicated in a survey done by ERC (2009), high potential employees are described by organizations as apart from being ambitious, interested in advancement and participating at a higher level within the organization, they are most importantly, customer-focused. Given dynamic business environment that is always driven by high expectations from customers, companies need employees who are able to anticipate changes and be proactive in dealing with chang ing customers‟ expectations.

In terms of methods used to identify HIPOs in organizations, the most common method was performance appraisal by the immediate superior and the least common method was nomination method. The popularity of performance appraisal as performance evaluation tool is also noted by Noe (2008). Performance appraisal done by immediate supervisor is much preferred by organizations to identify HIPOs because the close relationship between the employee and supervisor will ensure a more accurate assessment of employees job performance as compared to asking the top manager to do the evaluation. Such method is good in measuring past and current performance but it may not be the best method to gauge future performance especially if the employee is assigned a different position in different area or line. However, the method may be effective if it is coupled with performance review or discussion with the superiors. That may be reflected in one to one interview as shown in Table 3. The method allows the superior and the employee to discuss the latter‟s achievement, weaknesses, strengths, failures and potentials. Self-assessment was another common method used in identifying HIPOs among the respondents. It used psychological tests to assess employees‟ behavior, personality, styles and skills. It is commonly employed to identify weaknesses and strengths. One might question the reliability of the method but surveys (such as Church, 1997; Derr, Jones and Toomey, 1988) indicated self-rating is consistent with other‟s ratings. Nevertheless, the users were cautioned not to use it in performance appraisal because it is just best to be used as a tool to gauge potentials. The least common method used to identify

HIPOs in organizations was nomination method. This is consistent with the findings from Derr (1987), which stated that this method is preferred mostly in

European companies, but not in other countries. Nomination method is not popular probably because it tends to be subjective and open to bias from the rater ‟s position and some HIPOs employees might be side-lined.

Two most common methods to develop HIPOs were job enlargement and executive development programs. Stewart (1991) posited that executive development program (in-house) will help to develop HIPOs. This view is supported by Hollenback (1991) and Law (2008). Executive development programs provide a more systematic method and evaluation techniques to further develop HIPOs. Managers will have evidences on who are really the HIPOs,

10

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1 hardworking individuals and only being at the right place at the right time. Job enlargement was also popular method that gave real experience on the job. Peter and Smith (1996) said that job enlargement that gives opportunities to feel and experience the challenges is important to develop HIPOs. This statement is also supported by another study by Lombardo and Eichinger (2000) and Noe (2008), which recommended that a development program should have 10 percent formal training, 20 percent coaching or mentoring and 70 percent should be on job enlargement.

Table 4 indicated that mentoring and assignment to special projects were also quite commonly used. This signified that in Malaysia, the approaches in developing HIPOs are in line with what is recommended by the major scholars in the area. Mentors and coaches played the role as the persons to give professional guidance and psychological support. Generation Y prefers coaching much more than formal training. On the contrary, formal training is preferred most by older generations who are expected to be the coaches and mentors (Boatman and

Wellins, 2011). Therefore, older generations should learn to love such approach because if they fail to act as ones, the quality of the relationship between the coaches/mentors and the protégés would be negatively affected. As proposed by

Lombardo and Eichinger (2000) in their 70/20/10 formula, coaches play very pertinent role in HIPO development. They act as the gurus for the inexperienced employee who would guide and offer moral support to them. In other companies like Dell, Dow Chemical and GE, action learning is used (Conger and Fulmer,

2003; Fulmer and Conger, 2004). It is to assign HIPOs to certain projects and they will be guided by coaches/mentors in dealing with day-to-day problems and finally is to give recommendations to management.

Executive MBA programs were indicated as the least used probably because of the long duration that takes at least one year, unlike seminars/workshops which were shorter. Transfers, downward and upward movements were also less common. This is almost similar to job rotation to is normally used provide macro view to the HIPOs.

7. Conclusion

Generally, the study findings reveal that in most organizations in Malaysia, employees who are customer focused and possess self-direction in their career are highly valued. At this juncture, what is pertinent is coming up with ways to gauge the competencies among the HIPOs. It is also unwise to neglect the

“unsung heroes”, i.e. those who are high performers but having low aspirations to assume leadership positions. This is where employee assessment is crucial in identifying potentials and gauging talents. Various tools and approaches have to be used in order to capture the past contributions and project future performance.

Reinforcement system should be in place to motivate HIPOs to continue with excellent performance and reduce their intention to leave.

11

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

References

Ashton, C. and Morton, L. 2005, "Managing Talent for Competitive Advantage: Taking A

Systemic Approach To Talent Management", Strategic HR Review , Vol. 4 No.5, pp.28 – 31.

Barrington, L. 2010, CEO Challenge 2010: Top 10 Challenges , New York-The

Conference Board.

Boatman, J. and Wellins, R.S. 2011, Global Leadership Forecast 2011, Pittsburg, PA:

Development Dimensions International.

Church, A.H. 199 7, “Managerial Self-Awareness in High Performing Individuals in

Organizations ”, Journal of Applied Psychology , Vol.82, No.2, pp.281-292.

Conger, J.A. and Fulmer, R.M. 2003, “Developing Your Leadership Pipeline”, Harvard

Business Review , December, 10p.

Derr, C.B. 1987, “Managing High Potentials In Europe: Some Cross-Cultural Findings”,

European Management Journal, Vol. 5, Summer, pp. 72-80.

Derr, C. B., Jones, C., & Toomey, E. L. 1988, “Managing High-Potential Employees:

Current Practices in Thirty-Three U.S. Corporations”, Human Resource

Management, Vol. 27, No.3, pp. 272-290.

Economist Intelligence Unit, 2009, A New Ranking of the World’s Most Innovative

Countries: An Economist Intelligence Unit Report, Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. http://graphics.eiu.com/PDF/Cisco_Innovation_Complete.pdf. Viewed 21 July 2011.

Economist Intelligence Unit, 2011, Global Talent Index 2011-2015, Heidrick & Struggles

International, Inc.

Viewed 21 July 2011 http://www.globaltalentindex.com/Resources/gti-map.aspx.

ERC Survey Briefing December, 2009, Identifying and Developing High Potential

Employees . Ohio Human Resource Consultation Firm. http://www.ercnet.org/research/studies/Identifying_&_Developing_High_Potential_E mployees_Report.pdf. Viewed 26 February 2012

Fojt, M., Parkinson, S., Peters, J. and Sandelands, E. 2008, "The “Push-Pull” Approach

To Fast-Track Management Development: A Case Study In Scientific Publishing",

Journal of Workplace Learning , Vol. 20 No.2, pp.146 – 152.

Fulmer, R.M. and Conger, J.A. 2004, Growing Your Company's Leaders: How Great

Organizations Use Succession Management To Sustain Competitive Advantage .

New York: AMACOM.

12

Proceedings of 3rd Asia-Pacific Business Research Conference

25 - 26 February 2013, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, ISBN: 978-1-922069-19-1

Gritzmacher, K.J. 1989, “Staying Competitive Through Strategic Management of Fast-

Track Employees ”, National Productivity Review , Vol.8 No.4, pp. 421-432.

Groves, K.S. 2007, "Integrating Leadership Development and Succession Planning Best

Practices", Journal of Management Development, Vol. 26 No. 3, pp.239

– 260.

Hollenbeck, G.P. 1991, “What Did You Learn In School? Studies of A University

Executive Program ”, Human Resource Planning , No. 14, pp. 247-260.

Lankua, M.J. and Scandura, T.A. 2002, “An Investigation of Personal Learning In

Mentoring Relationships: Content, Antecedents, and Consequences ”, Academy of

Management Journal , Vol. 45 No. 4, pp. 779-90.

Law, K.A. 2008, “Practices of Management Development: A Malaysian Case Study”,

International Education Studies , Vol.1 No.2, pp. 76-88.

Lombardo, M. and Eichinger R. 2000, The Leadership Machine, Minnesota: Lominger

International.

Noe, R. A. 2008, Employee Training and Development, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pepermans, R., Vloeberghs, D. and Perkisas, B. 2003, “High Potential Identification

Policies: An Empirical Study among Belgian Companies ”, Journal of Management

Development , Vol. 22, No. 8, pp. 660-78.

Peters, J. and Smith, P. 1996, Developing High Potentials: The Action Learning

Approach , unpublished working paper.

Schumacher, S. January, 2009, High Potential Employees, Rock Products. New York:

Prism Business Media.

Snipes, J. 2005,

“Identifying and Cultivating High-Potential Employees”.

Chief Learning

Officer Magazine , pp. 1 –6.

Stewart, T.A. 1991, “GE Keeps Those Ideas Coming ”,

Fortune , August 12, pp. 41-49.

The Edge Malaysia, (Dec 21 – 27, 2009), “More Companies Expected to Lift Pay

Freeze Next Year

”, Issue 786. http://www.theedgemalaysia.com/managent/157119mere-companies-expec-ted-to-lift-pay-freeze-next-year.html. Viewed 21 July 2011.

13