Proceedings of 26th International Business Research Conference

advertisement

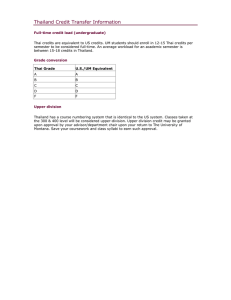

Proceedings of 26th International Business Research Conference 7 - 8 April 2014, Imperial College, London, UK, ISBN: 978-1-922069-46-7 Drivers and Barriers for Implementing Environmental Management in Beverage Processors: A Case of Thailand Auttasuriyanan Pakpoom** and Setthasakko Watchaneeporn *** The main purpose of this study is to gain a clearer understanding of key determinants that drive environmental management and barriers that hinder its development. The study employs semi-structured interviews with key informants accompanied by site observations. Key informants include production, environmental and plant managers of six beverage companies, including three Thai and three multinational companies in Thailand. It is found that corporate image, government subsidies, top management leadership and education institutes are four primary factors influencing the implementation of environmental management in the beverage processors. No demand from Asia buyers, employee resistance to change and lack of environmental knowledge are identified as barriers. Keywords: Environmental Management, Beverage, Government Subsidies, Education Institutes, Employee Resistance, Environmental Knowledge, Thailand 1. Introduction At the present time, business is under pressure from social groups adversely affected by its activities: those in the state sector, customers, communities and international organizations. These parties are demanding that business considers the environmental impacts of its operations (Hopwood, 2009; Zhu and Sarkis, 2006). Examples of such pressure are the issuing of legislation requiring businesses to carry out environmental impact assessments, publish sustainability reports and issue environmental management standards (Robinson et al., 2006). As a result, for businesses to uphold their commitment to various stakeholders in society, for their activities to gain social acceptance (Delai and Takahashi, 2011) and to ensure long-term sustainability, they must apply the Triple Bottom Line principle. This principle involves consideration of economic and social development along with environmental management (Elkington, 1998). Environmental management is considered a part of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). This paper aims to at least in part fill that gap, by exploring key determinants that drive environmental management and barriers that hinder its development. Two key research questions are address: RQ1. What are key determinants that drive implementation of environmental management for beverage processors in Thailand? RQ2. What are barriers to implementation of environmental management for beverage processors in Thailand? **Auttasuriyanan Pakpoom. Thammasat Business School, Thammasat University, Bangkok 10200, Thailand. E-mail: pakpoom.ibmp@gmail.com ***Watchaneeporn Setthasakko, Ph.D is an Associate Professor at Thammasat Business School, Thammasat University, Bangkok 10200, Thailand. E-mail: wsetthasakko@yahoo.com 1 2. Literature review 2.1 Sustainability Sustainability stands as the means of meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (World Commission on Environment and Development; WCED, 1987). To move towards sustainability, business firms need to look at everything from a holistic perspective in order to understand the interconnections between economic growth and environmental and social sustainability. Also, they have to shift their thinking from the conventional way of viewing impact on the environmental and society to that of creating a long-term vision of environmental and social sustainability or Corporate Social Responsibility (Hoffman, 2000; Schaltegger et al., 2002; Setthasakko, 2007; Welford, 2000). 2.2 Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental management Corporate Social Responsibility, or CSR, is a continuing commitment by business to operate ethically and play a part in economic development. This can be done by improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families, as well as becoming involved in the development of local communities and wider society (The World Business Council for Sustainable Development; WBCSD, 1999). There are 3 types of CSR which can be adopted in business operations (Corporate Social Responsibility Institute; CSRI, 2008; Thai Corporate Social Responsibility, 2010): 1. CSR-after-process: This involves corporate activities that benefit society in various ways. These activities take place following, or separately from, main corporate activity. Such activities can include those whose purpose is to enhance corporate image, such as planting trees, donating educational grants, awareness campaigns and giving aid to victims of natural disasters. 2. CSR-in-process: This type of CSR involves incorporating social responsibility into the main business operations of the company, without having been compelled to do so. This type of CSR includes responsible methods of making profits, such as producing goods which do not harm the environment, pollution prevention or control in the production process to limit impacts on communities, and being committed to employee welfare and responsibilities to customers. 3. CSR-as-process: This involves CSR activities which do not seek profit for the organization; in other words, the organization‟s purpose is to bring benefits to society through all its practices. Examples are charitable trusts or foundations. Foran, 2001; Frederick et al, 1992; Jackson and Hawker, 2001; Lea, 2002; Marsden, 2001and Van Marrewijk, 2003 point out that environmental management is part and parcel of CSR. This viewpoint is in line with that of the European Commission (2011), which defines CSR as the incorporation of concern for society, the environment, human rights and 2 consumer rights into business processes, as well as interaction with stakeholders, undertaken voluntarily. Under this definition, it is clear that environmental management is included. Environmental management is defined as the effective handling of natural resources and the environment, whether in exploration, storage, maintenance and conservation in order to minimize negative environmental impact. It can also benefit humanity by ensuring that resources remain for continuous use, without shortages or other problems (Brorson and Larsson, 1999; Robert, 2000). 2.3 Beverage processing companies in Thailand Even though Beverage processing companies have brought great benefits in expanding the Thai economy, continuous expansion has also had environmental and social impacts due to the ongoing rise in demand for water in drinks production. Groundwater has been extracted for industrial use since 1978, extraction rates increasing by 3.04% per year. This has resulted in the water table reaching crisis levels in 7 provinces, namely Bangkok, Samut Prakan, Samut Sakhon, Nonthaburi, Nakorn Pathom, Pathum Thani and Ayutthaya (Department of Groundwater Resources, 2012). Due to this groundwater crisis, legislation has been passed to limit and control groundwater extraction and use in the affected areas, as well as increasing the fee to be paid on extraction to match that paid for mains water. Some in Beverage processing companies, however, still prefer to use groundwater as a raw material in the production process, as using mains water, which is chlorinated, may cause problems in the production process and affect product quality. Furthermore, using mains water instead increases operational costs such as laying pipes, pump installation and dechlorination to make the water suitable to be used in the production process, in order to preserve product taste (Koontanakulwong et al., 2007). Groundwater extraction for use in beverage production has resulted in the lowering of the water table in the central region of the country. This has led to subsidence and flooding in coastal areas where tidal surges have occurred, causing saltwater intrusion into freshwater areas. This has happened in the coastal areas surrounding Bangkok, Samut Prakan and Samut Sakhon (Department of Groundwater Resources, 2012). 3. Research methodology This paper focused on six beverage processing companies used as case studies, employing a system perspective as a conceptual guide. An exploratory case study was conducted because this method excels at research situations involving a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life contexts (Yin, 2003). This study used a multiple-case design for cross-site comparison and analytic generalization. The research was conducted by semi-structured-interviews with key informants, site observation and documentation during the winter of 2013. The informants are production, environmental and plant managers. They were asked a core set of semi-structured questions and probed for elaborations and explanations of issues as they emerged. The interview format covered the following areas: 3 background of company; implementation of environmental management; and barriers to implementation of environmental management The interviews ranged in length from one hour to two hours. Extensive notes were taken at the time and written up later the same day. Data were analyzed by using the method suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994) for qualitative analysis: data reduction, data display matrix and conclusion drawing and verification. By using this method, we can understand determinants and barriers to the implementation of environmental management for beverage processors in Thailand. In order to increase the trustworthiness of the study, site observations were undertaken, allowing the researcher to obtain a “system” view of production processes and environmental management practices, including wastewater treatment and solid waste management. 4. Companies profile The companies studied are located in the Central and East regions of Thailand. The criterion for selecting the six beverage processing companies was primarily based on the fact that they are Thai company or multinational company has implementing environmental management. The chief differences among the companies studies are years of operation, authorized capital, number of employees and type of product. Confidentiality was agreed upon as a condition prior to research access. The companies are referred to here under the pseudonyms Company A, Company B, Company C, Company D, Company E and Company F. The features of the companies are given below. Company A was established about 31 years ago with an aim to consolidate its leading spirits business in Thailand. It is a Thai company. At present, it has authorized capital of approximately $ us 152 m and employs 450 people. The company‟s products are exported to international market, including the European Union and the Asia-pacific region. The company has received many international management certificates, including ISO 9001:2008, ISO 14001:2004 and ISO 22000:2005. Company B was established about 35 years ago. It is a Thai company. Authorized capital is approximately $ us 8 m and employs 2,450 people. It is the leading energy drink company in Thailand. The products of company B are exported to 160 countries all over the world. Its involvement in environmental management includes participation in Green Industry project of Ministry of Industry. Company C was established about 50 years ago. It is a Thai company. At present, this company employs 170 people. It is a leader in Alcohol Company in Thailand. Its involvement in environmental management includes participation in Cleaner Production project. The company has received ISO 14001:2004. Company D was established about 20 years ago. It is a multinational company from Netherlands. It has an authorized capital of approximately $ us 30 m and employs 135 people. At present, some products are exported to Asian countries. Environmental management is illustrated by the fact that it was the first Brewery Company in Thailand that 4 implements a “Water for Life” project. The project involves a research on improving the efficiency of brewery‟s wastewater treatment following nature-by-nature conservation approach. The company has received many international management certificates, including ISO 9001:2000, ISO 14001:2004 and ISO 22000:2009. Company E was established about 19 years ago with the authorized capital of approximately $ us 56 m. It is a multinational company from Taiwan. This company employs 257 people. At present, it is the leading mixed vegetable and fruit juice Beverages Company in Thailand. Most of its products are exported aboard, including to the US, the Middle East and other Asian countries. The control of pollutants is within all applicable government requirements. Company F was established about 32 years ago. It is a multinational company from the United States. Authorized capital is approximately $ us 29 m. It is a leader in Sparkling Beverages Company in Thailand and employs 1,190 people. Environmental management is illustrated by the fact that it was the first Sparkling Beverages Company to be granted the ISO 14001 certification in Thailand. 5. Findings 5.1 Drivers for implementing environmental management The driver for implementing environmental management are corporate image, government subsidies, top management leadership and education institutes. Corporate image Beverage processing companies are viewed as having negative impacts on the environment and society. They are seen as being responsible for taking away water resources from communities, for water pollution and foul odours and leaching of effluent into community water sources. Thai culture is also group-orientated rather than individualistic. The need to build a good corporate image for companies in order to be accepted in coexisting with communities has resulted in pressure for both Thai and multinational companies to carry out environmental management. In an interview, a plant manager was quoted as saying: “…Even though communities have sometimes settled in the area after the establishment of industry, if they cannot live in the area then neither can we. We might be reported to the authorities by the community for foul-smelling effluent. To build a good image to ensure acceptance by the community, we follow ISO 14001 to show the community that we are truly committed to the environment and are open to scrutiny by external parties on an annual basis...” (Plant Manager, Company A) “…Even if we were here before the community, we still want to be able to coexist with it without generating resentment and without the risk of being reported to authorities regarding effluent from the production process, as has happened in the past. We have, for example, had people complain about foul-smelling effluent and its strange colour. Because of this, in order to build a good image, we practise environmental management that is effective and in accordance with Department of Industrial Works regulations…” (Plant Manager, Company C) 5 “…We practise environmental management because we want to be accepted by the community, so we (a brewery) have set up a Water for Life project. We grow plants that help treat the effluent and invite local people living around the brewery to collect these plants, which can be used as animal feed or in handicrafts. That raises income for their families and the community…” (Environmental Manager, Company D) “…Even though we have been here for 32 years, before the local community settled here, we wish to live in harmony with the local people. That is why we place importance on the environment, as can be seen from our exclusive use of groundwater and mains water without extracting water from the Chao Phraya River. This is despite the fact that our filtering system can clean the water and can also help greatly reduce water costs. However, management policy is not to take water from the surrounding communities, which has helped us to gain the confidence of the local people…” (Plant Manager, Company F) Government subsidies The Department of Industrial Works only awards subsidies to companies which practise environmental management in line with legislation and have had at least 50 years of good relations with the Department of Industrial Works. These subsidies are another motivation for Thai companies to pay attention to environmental management, as stated by a plant manager in an interview: “…Even though the Department of Industrial Works does not force us to join the Green Factory scheme or carry out ISO 14001, we are happy to get involved, as it is a good opportunity for us as a state enterprise to preserve good relations with state bodies. We have maintained good relations with the Department of Industrial Works and have followed environmental management legislation for 50 years. As a result we receive a 40 million baht investment subsidy from the Department of Industrial Works, which is 20% of the total investment needed to build our new environmentally friendly alcohol distillation tower…” (Plant Manager, Company C) Top management leadership Due to the hierarchical nature of Thai culture and society, senior management are the sole decision makers, while lower ranking staff merely obey orders. Because of this, senior managers in both Thai and multinational companies are major players in the success of environmental management via budget allocation, designated areas within breweries or factories and liaison with suppliers, as well as incorporating environmental issues into company policy. This results in staff cooperation in environmental management, as stated in the following interview of a plant manager: “…The goal of the company president is to bring the factory in line with ISO 14001 criteria by next year. The president has always supported the role of staff in environmental management. If there is any practical aspect that staff do not understand, the president will send staff to study real life examples from other companies which successfully operate those systems, so that staff can see how we can apply these practices to our factory…” (Plant Manager, Company B) 6 “…In the early days of our Water for Life project, which used plants to treat effluent in order to save energy and reduce chemical use, we were supported by senior management, who are from overseas. They provided the budget and a 1.97 acres space in the factory grounds as an experimentation area…” (Environmental Manager, Company D) “…The company president plans to make our factory into a Level 4 Green industry within 3 years. At present, the president is speaking to our 40 to 50 suppliers, asking them to cooperate in environmental management so that it runs through the entire supply chain…” (Environmental Manager, Company E) “Apart from the environmental policy handed down from our American parent company, our management has always placed emphasis on the environment from the earliest days of the company, founded in 1951. This can be seen in our status as the first factory in the network under our parent company, as well as being the first beverage factory in Thailand to meet ISO 14001 standards” (Environmental Manager, Company F) Education institutes Universities have an important role to play in supporting beverage processing companies in practicing environmental management to exceed required standards. They have done this by providing equipment and up to date expertise to both Thai and multinational companies, including using waste products from the production process to feed animals and treating factory effluent by using plants, in order to reduce the use of chemicals and to save energy. In an interview, an environmental manager commented: “…We have joined forces with Windows and NIDA, which have supported us in our environmental management and have helped set up our pollution control project free of charge. The project aims to reduce incomplete combustion. Tests have shown that there is now no dioxin release detected from the factory boiler” (Environmental Manager, Company A) “…The brewery‟s environmental management practices are based on collaboration with Kasetsart University, such as in the Water for Life project, which uses plants to help treat effluent. The brewery wishes to be an initiator in effluent treatment to prevent offensive smells which disturb local communities. Apart from this, to deal with waste products which cannot be re-used, such as brewer‟s grain, the brewery has joined hands with Thammasat University‟s farm to convert it into animal feed” (Environmental Manager, Company D) 5.2 Barriers to implementing environmental management Implementing environmental management is challenging. There are obstacles during the Implement, the research identified primary barriers: No demand from Asia buyers, employee resistance to change and lack of environmental knowledge. No demand from Asia buyers An important barrier to the practice of environmental management by both Thai and multinational beverage processing companies that export to consumers in Asia (China, Hong 7 Kong, Myanmar, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia) is the lack of interest of those markets in environmental management. These countries are more interested in product pricing, quality and safety, according to the following interviews: “…At present we export alcoholic beverages to Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar and Hong Kong. Our customers are not currently interested in environmental issues, neither do they inquire about ISO 14001 standards, which we have been recognised as meeting. Instead, they focus on consistency of pricing and quality...” (Plant Manager, Company A) “…Our overseas customers, whether they be in Myanmar, Laos or Cambodia, are not interested in our ISO 14001 standards, but rather in quality and pricing…” (Environmental Manager, Company D) “…A proportion of our fruit and vegetable beverages are exported to America, the Middle East, Myanmar, Vietnam, Laos and Malaysia. Our Asian customers are not interested in our factory‟s environmental management practices, but rather focus on quality and safety. For example, Chinese customers are only concerned with whether the tea leaves used in the production process are organic…” (Plant Manager, Company E) Lack of environmental knowledge Another obstacle to the implementation of environmental management occurring in Thai and multinational companies is the lack of environmental knowledge on the part of staff. This is especially true for environmental standards such as ISO 14001, some points of which are hard to interpret, leading to environmental department personnel taking considerable time in learning about them, or liaising with environmental consultancy firms for project advice. Following this process, staffs in other departments are then trained prior to undertaking their duties, as related in this interview: “…Most factories take no more than 2 years for the implementation of ISO 14000, but our factory has taken as long as 3 years. That is partly because of a lack of comprehension by staff, which meant that the factory has had to have an advisor give a talk and arrange training for all factory staff…” (Plant Manager, Company C) “…With the emergence of new environmental standards such as ISO 14001, there are problems with interpreting some points, particularly as they are written in English. As a result, our environment department staffs have to take time to familiarize themselves with the standards. Then the staffs have to be trained in operations in other parts of the factory prior to ISO 14001 implementation, as ISO 14001 implementation depends on cooperation and liaison between different departments…” (Environmental Manager, Company F) Employee resistance to change Employee resistance is another barrier to implementing environmental management, especially in Thai companies which are state enterprises. This is due to state enterprises being wholly government-owned, the government having more than a 50% shareholding, or being under direct or indirect government supervision. This has meant that the 8 organizational culture of such bodies remain like that of the civil service, where staff are unmotivated to comply in implementing environmental management, which they see as increasing their workload. An interview stated that: “…Despite being a state enterprise, our internal culture is similar to that of the civil service, working day to day. When we first started the Green Factory and Clean Technology project to cut production waste and pollution, there was resistance from older staff members to the implementation of ISO 14000. Even though we pointed out that environmental issues were a concern of everyone in the factory, they still saw that the old way of doing things was alright and wondered why anything had to change…” (Plant Manager, Company C) 6. Conclusions, Limitation and Future research The findings show that key determinants that drive implementation of environmental management consist of corporate image, government subsidies, top management leadership and education institutes. No demand from Asia buyers, employee resistance to change and lack of environmental knowledge are identified as barriers to implementation of environmental management for beverage processors in Thailand. A deeper understanding of these factors derived from case study research with the use of indepth interviews and site observations will assist in the implementing environmental management toward sustainability. Furthermore, in order to improve generalization of the findings, future research should broaden the simple. It would also be beneficial to pursue comparative research between industries and countries. 7. References Brorson, T., Larsson, G. 1999, Environmental Management, EMS AB, Stockholm, pp.34. Delai, I., Takahashi, S., 2011, “Sustainability measurement system: a reference model Proposal”, Social Responsibility Journal, Vol.7, No.3, pp.438-471. Elkington, J. 1998, “The „triple bottom line‟ for twenty-first-century business. In J. V. Mitchell (Ed.), Companies in a world of conflict: NGOs”, sanctions and corporate responsibility, pp. 32–69. London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs/Earthscan. Foran T. 2001, Corporate Social Responsibility at Nine Multinational Electronics Firms in Thailand: a Preliminary Analysis, report to the California Global Corporate Accountability Project. Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainable Development: Berkeley, CA. Frederick W, Post J, Davis KE. 1992, Business and Society. Corporate Strategy, Public Policy, Ethics, 7th edn. McGraw-Hill: London. Hoffman, A.J. 2000, Competitive Environmental Strategy: A Guide to the Changing Business Landscape, Island Press, Washington, DC. Hopwood, A.G. 2009, “Accounting and the environment”, Accounting, Organizations 9 and Society, Vol.34, pp. 433-9. Jackson P, Hawker B. 2001. Is Corporate Social Responsibility Here to Stay? http://www.cdforum.com/research/icsrhts.doc [23 June 2003]. Lea R. 2002, Corporate Social Responsibility, Institute of Directors (IoD) member opinionsurvey.IoD:London.http://www.epolitix.com/data/companies/images/ Companies/Institute-of-Directors/CSR_Report.pdf [23 June 2003]. Marsden C. 2001. The Role of Public Authorities in Corporate Social Responsibility. http://www.alter.be/socialresponsibility/people/marchri/en/displayPerson Robert Rutherfoord, Robert A. Blackburn, Laura J. Spence, (2000), "Environmental management and the small firm: An international comparison", International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, Vol. 6, Iss: 6, pp.310 – 326 Robinson, H.S., et al., 2006, “Steps: a knowledge management maturity roadmap for corporate sustainability”, Business Process Management, Vol. 12 No.6, pp.793-808. Schaltegger, S., Herzig, C., Kleiber, O. and Müller, J. 2002, Sustainability Management in Business Enterprises: Concepts and Instruments for Sustainable Organization Development, The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, Bonn. Setthasakko, W. 2007, “Determinants of corporate sustainability: Thai frozen processors”, British Food Journal, Vol. 109 No. 2, pp.155-68. seafood Van Marrewijk M. 2003, Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics 44: pp.95–105. WBCSD (World Business Council for Sustainable Development) 1999, Corporate Social Responsibility: Meeting Changing Expectations. World Business Council Sustainable Development: Geneva. for WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development) 1987, Our Common Future („The Brundtland Report‟; Oxford, UK; Oxford University Press). Welford, R.J. 2000, Corporate Environmental Management 3: Towards Sustainable Development, Earthscan, London. Zhu, Q. and Sarkis, J. 2006, “An inter-sectoral comparison of green supply chain management in China: Drivers and practices”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol.14, pp.472-486. 10