Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference

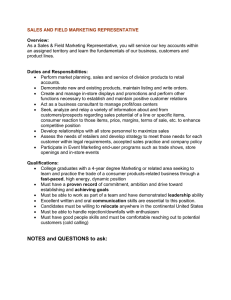

advertisement

Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 Impact of Pre-Shopping Activities on Purchase Decisions at the Point of Sale Silvia Bellini and Maria Grazia Cardinali* Over the past few years, retailers and manufacturers alike are increasing their attention and resources allocated to the practice of shopper marketing with the aim to influence consumers “in shopping mode”, when they are prepared to make a choice, along and beyond the entire path-to-purchase. Environmental changes, specifically the economic crisis and the growing penetration of digital technologies, have produced significant changes in shopping habits designed to gradually reduced the effectiveness of in-store marketing levers in influencing shopping behaviour. A new scenario seems to be opening up where more planning and preparation for shopping is carried out before the customer enter the store. Our work intends to explore the relationship between pre-trip activities and shopping behaviour instore in order to understand if marketing levers could still influence consumers’ decisions in-store or, on the contrary, a more prepared consumer limit the effectiveness of shopper marketing by reducing impulse buying. Field of Research: Marketing (Retailing) 1. Introduction Over the past few years, retailers and manufacturers alike are increasing their attention and resources allocated to the practice of shopper marketing with the aim to influence consumers “in shopping mode”, when they are prepared to make a choice, along and beyond the entire path-to-purchase. This practice, knows as “Shopper marketing” (Shankar, 2011), is regarded as a priority by both retailers and manufacturers around the world for its ability to influence shoppers decisions in store. According to a recent market research (Popai, 2012), in Italy at least two out of three purchase decisions are made in store and this data would strengthen the growing strategic importance of the point of sale and all those levers which are operated in store to influence and affect the buying behavior of the consumer. In the last decade, industrial companies have gradually shifted their strategic focus from a traditional marketing approach, oriented to create awareness using pull and push strategies, to a shopper marketing approach, oriented to create awareness by influence triggers in the shopping cycle in the belief that in-store marketing levers are more effective than the traditional ones (communication out of store). At the same time, grocery retailers have invested increasing marketing resources in in-store promotions with the aim to influence the buying behavior in the store. Recent environmental changes, specifically the economic crisis and the growing penetration of digital technologies, have produced significant changes in shopping habits designed to create a new scenario for shopper marketing. Thanks to technologies, consumers are now able to collect information out-of-store, carrying out * Silvia Bellini, Department of Economics, University of Parma – ITALY – email: silvia.bellini@unipr.it Maria Grazia Cardinali, Department of Economics, University of Parma – ITALY – email: mariagrazia.cardinali@unipr.it Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 several and various pre-trip activities, such as comparison of pricing, promotions and range among different retailers. Consumers, thus, enter the store much more prepared and they are able to make shopping quickly, only looking for products they had planned to buy, guided by a digital shopping list, digital coupons or printed customized promotions. In this new context, important questions are arising: what is the relationship between pre-shopping behavior and in-store shopping behavior? How this relationship varies among store formats? Can in-store marketing levers still influence consumers as in the past or their new planning attitudes limit the impact of in-store shopper marketing? These questions are relevant both from an academic viewpoint, as emerged from the literature described below, as well as from a managerial one. On this latter point, the answer can guide decisions as to how to allocate marketing budget to out-of-store versus in-store marketing activities, as well as how to differentiate these activities among store formats. 2. Literature Review Shopper marketing has been studied along two perspectives: some contributions have assumed a broad perspective by studying shopper marketing as a whole and in a comprehensive way (GMA/Delloitte 2007, Oxford Strategic Marketing 2008, Harris 2010, Retail Commission on Shopper Marketing 2010, Shankar 2011, Shankar et al. 2011), while others authors have assumed a narrow perspective focusing on one or few specific aspects included in it (Kahn and Schmittlein 1989, Chandon et al. 2002, Inman et al. 2004, Sinha and Uniyal 2005, Larson et al. 2005 and 2006, Neff 2008, Chandon et al. 2007, 2009, Inman et al. 2009, Dulsrud and Jacobsen 2009, Suher and Sorensen 2010, ECR Europe 2011, Bell et al. 2011). In our work, we assume the definition given by Shankar et al. (2011) who defined shopper marketing as “the planning and execution of all marketing activities that influence a shopper along, and beyond, the entire path-to-purchase, from the point at which the motivation to shop first emerges through to purchase, consumption, repurchase, and recommendation”. In other words, shopper marketing differs from traditional marketing because it is recognizes the need to understand, activate and engage with consumers when they are in the role of shopper. Several studies explored the relative influence of in-store and out-of-store shopper marketing activities on purchase showing the high degree of decision-marketing in store (Deloitte Research 2007, Inman et al 2009, GMA 2010, Popai, 2012). Decisions made in-store have been defined in literature as “impulse buying” (Beatty and Ferrel, 1998), that are a sudden and immediate purchases with no pre-shopping intentions either to buy a specific product category or to fulfill a specific buying task. Impulse buying do not have to be confused with unplanned buying: the first is a spurof-the-moment purchase with little thought while the latter is buying since the shopper forgot to put an item on her list. Thus, according to this definition, in our work we consider “impulse buying” as purchases decided in-store and “planning buying” as purchases decided out-of-store, during pre-trip activities in the early steps of the shopping cycle (motivation to shop, search, evaluation and category/item/brand selection). Shopper marketing activities could influence all the shopping cycle, thus pre-trip activities and shopping behavior in-store. While this latter area has been studied in literature during the past years, the first one has been less explored because it has known a development only recently due to environmental changes. Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 In particular, changes in economy and technology have highlighted the importance of pre-trip activities and the potential role of shopper marketing in influencing them. On one hand, due to the global economic downturn and the associated diminished disposable income, more shoppers are now searching more information before enter a store and evaluating more alternative before to decide where and what to shop. On the other hand, the deep penetration of technological developments such as digital media and mobile devices among the population has opened up new opportunities to influence shopper attitudes and behavior (Shankar and Balasubramanian, 2009), particularly in the retail environment (Shankar et al. 2010). Environmental changes have opened up a new scenario for shopper marketing: as emerged from the recent literature (Shankar, 2014), shopper marketing is today evolving, shifting from a first phase (Shopper Marketing 1.0), addressed interesting issues, primarily relating to in-store marketing, to a second phase (Shopper Marketing 2.0) that will significantly extend to out-of-store marketing, including online and mobile marketing, resulting in an integrated practice. In this new environment, to formulate and execute effective shopper marketing strategies, managers need to better understand the complete picture of how online, offline, mobile and in-store marketing influence shoppers in the path-to-purchaseand-beyond cycle. As suggested by Shankar et al. (2011), there is a need to evolve from focusing on in-store to focusing on all stages in the shopping cycle. 3. Research Aims and Methodology Starting from research avenues emerged in recent literature, our work intends to explore the relationship between pre-shopping behaviour and shopping behaviour instore, with the aim to understand how pre-trip activities have changed in the new market scenario and how they have influenced the in-store shopping behaviour. Specifically, our work intends to verify the following hypotheses: H1 – Pre-trip activities have increased in importance and diffusion H2 – Pre-trip activities vary among store formats H3 – Pre-trip activities influence shopping behaviour by increasing planning buying in store, hence reducing impulse buying H4 – A profile of shopper much oriented to preparation and planning of grocery purchases is emerging In order to verify these hypotheses, we conducted a survey of 1050 shoppers based on a structured questionnaire. The research focused on three Italian grocery retailers operating in different store formats (EDLP supermarket, hi-low supermarket and hypermarket). 4. Findings and Discussion In order to verify our first hypothesis, we have analysed how consumers carry out pre-trip activities before grocery purchases, exploring the amount of time devoted to a list of pre-trip activities as well as the number of diverse activities carried out. First, our research shows the growing importance of the searching information process out-of-store: 65 percent of consumers interviewed search information out-of-store while only 35 percent of them search information in-store. Secondly, the preparatory activities is not limited to the preparation of a traditional shopping list, but regard several activities: in particular, before choosing the store in which making their grocery purchases, consumers search information about pricing and promotion (48 percent of interviewed done this activity always or often), compare flyers on line (92 Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 percent) as well as off line (22 percent), compare retailers visiting their web site (22 percent) or aggregator on line (20 percent), and prepare a written shopping list (46 percent). In sum, pre-trip activities have increased in importance and diffusion, confirming our first hypothesis. However, are these pre-trip activities carried out in the same way among store formats? In order to answer this question, and verify our second hypothesis, we have constructed an index that synthetizes all the pre-trip activities carried out before shopping (Table 1). The index, called “preparatory index”, includes all the pre-trip activities identified above and can range from zero (if consumers do not make any preparatory activity) to 100 (if consumers make all the activities). Table 1: Preparatory Index Composition Pre-trip activities Collection of information on prices and promotions (on and off line) Consultation leaflets (print and digital) Comparison retailers (on and off line) Written Shopping list Total pre-trip activities Weight (%) 20 20 20 20 100 The results show a higher “preparatory index” in the hypermarket than in the other store formats analyzed (Table 2) confirming our second hypothesis according to which pre-trip activities vary among store formats depending on their strategic positioning. The hypermarket, for its characteristics concerning range (wide and deep), pricing strategies (high intensity promotion), location (much time to reach the store), require a more intense pre-trip activities compared to the other store formats where the shopping can be simpler and more “time saving”. Table 2 – Preparatory index by store formats Store formats Hypermarket Supermarket Hi-Lo Supermarket EDLP Preparatory index 30,5 27,1 20,4 Considering these findings, it become interesting to understand if a shopper that systematically makes pre-trip activities before shopping is also a more “planned shopper” that tends to use, more than ever, a shopping list (mental or written) as a guide in the store looking for those products and those brands which had planned to purchase. In order to understand the influence of pre-trip activities on the balance between planning and impulse buying orientation, testing our third hypothesis, we explored the degree of planning of grocery purchases. Our research shows that the percentage of consumers who bought products they have planned before is higher than the percentage of those who made “impulse buying”: almost half of the shoppers interviewed has bought a products they had Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 planned before, because it was a necessary product or because he knew that it was in promotion; on the other hand, impulse buying are 26 percent (Table 3). Table 3 – The degree of planning of grocery purchases Degree of planning Frequency (%) Planned purchase of product (I need it) 42% Planned purchase of brand (not of product) 9% Planned purchase of category (not of product) 17% Planned purchase of product because promoted 6% Not planned, but purchased because promoted 9% (impulse buying influenced by promotion) Not planned (impulse buying) 17% These results confirm our third hypothesis: a more prepared and aware consumer, who devotes much time to search for information (about prices, products, brands) out-of-store, shows a more planning behavior, which means that he decides to buy the products and categories of which he had planned the purchase. In order to have an indicator for each customer about his degree of impulse buying, we have constructed the “impulse buying index” which can range from zero (planned purchase of product) to 100 (not planned), as shown in Table 4. Finally, it become interesting to understand if a planning buying orientation is more widespread than impulse buying orientation. For this purpose, we conducted a cluster analysis taking into consideration the variables concerning with the preparatory activities out-of-store and the shopping behaviour in-store. Specifically, we have considered the following variables: the preparatory index (as shown in Table 1), the index of impulse buying (as shown in Table 4), the time spent in front of the display (in second) and the share of wallet (as an indicator of knowledge of the store). Table 4 – Impulse buying index composition Degree of impulse Not planned (impulse buying) Not planned, but purchased because promoted (impulse buying influenced by promotion) Planned purchase of product because promoted Planned purchase of category (not of product) Planned purchase of brand (not of product) Planned purchase of product (I need it) Index 100 80 60 40 20 0 The cluster analysis revealed three segments of shoppers which differ for the effort put in pre-trip activities, time in front of display, impulse/planned purchase ratio and share of wallet (Table 5). Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 Table 5 – Cluster analysis output Variables Preparatory index Index of impulse purchases Time in front of display (second) Share of wallet (%) Cluster 1 29,35 28,45 117,1 Cluster 2 28,53 11,47 20,97 Cluster 3 26,53 89,48 23,15 62 57 58 The first cluster consists of 9 percent of consumers who can be defined as “Working shoppers” for their high engagement in all pre-trip activities (higher preparatory index) and long time spent in front of the display. These professional shoppers indulge in some impulse buying – possibly driving their confidence from the amount of preparatory work they do. The second cluster consists of 62 percent of consumers who can be labelled as “Grab & Go Shoppers” for their fastest in-store shopping process. Consequently, their impulse buying is reduced to a minimum. Finally, the third cluster consists of 29 percent of consumers, the “Fast impulse shoppers”, driven by impulse buying and little influenced by pre-trip activities. These results confirm our last hypothesis: a profile of shopper much oriented to preparation and planning of grocery purchases is emerging. 4. Conclusions and Implications Our research finds that pre-trip activities have increased in importance and diffusion, enabled by the growing penetration of new technologies and stimulated by a change in shopping behavior due to the economic crisis. The preparatory activities are common and span a variety of online and offline tasks and customers see these activities as having an influence on their choice of store, category and brands. Instore behavior seems to be more directed by pre-trip activities than generally assumed. The increasing pre-trip activities, in fact, has influenced shopping behavior in-store by reducing impulse buying and increasing planning purchases. Given these findings, a question is become of paramount importance: what about the effectiveness of marketing levers in influencing shopping behavior? Can in-store marketing still influence consumers as in the past or their new planning attitudes limit the impact and the effectiveness of in-store shopper marketing levers? This question is of paramount importance for managers in order to decide how to allocate marketing budget to out-of-store versus in-store marketing activities, how to differentiate these activities among store formats and, finally, how to improve effective and efficient in managing their products. In recent years, the resources allocated to price promotions have increased as well as the share of products sold in promotion. Increasing in price promotions has been accompanied by an increase in trade marketing resources designed to support instore marketing activities. Until today, the flyer has been the most important means to influence consumers’ decisions in-store, while the point of sale has been the main medium of communication of promotional initiatives, engaging a growing share of trade marketing resources. Today the diminishing returns in promotions and the risk that planning buying could reduce in-store marketing levers effectiveness raise new concerns for managers who are wondering if it would be better to invest more resources out-of-store using a multiple media mix (web, mobile, social, etc.) reducing investments in the point of sale. Despite changes in shopping behavior, the point of sale will continue to have an Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 important role in influencing consumers’ decisions, attracting therefore investments from both retailers and manufacturers. As well as retailers will continue to need industrial contributions for managing in-store activities and promotions, manufacturers could not simply affect and change behavior through out-of-store marketing levers giving up in-store activities. The out-of-store influence of shoppers is potentially quite substantial, and marketers have to look for new ways to influence shoppers perceptions early in shopping cycle, without diminish the role of the point of sale and the role of in-store marketing levers. As pointed out by Shankar et al. (2011), a new scenario is opened up for shopper marketing: as technology enables shoppers to increasingly use and engage with multiple channels, looking for consistent information even during pre-trip activities, retailers may look for innovate shopper marketing in-store in order to influence decisions of consumers who are much more conscious and prepared that in the past, thanks to the amount of information they have collected out-of-store, during pre-trip activities. Today retailers have growing opportunities to influence shopper decisions in store using technology (such as RFID, mobile technology, TV networks, virtual reality), instore promotional instruments, innovations in aisle-placements and shelf-space management. In particular, new technologies are opening a new phase for promotions in-store in which shoppers will have a more active role: over to classical promotions, addressed to all customers and massively communicated in-store (through display and layout), retailers can implement customized promotions, communicated directly to shopper through mobile devices, which will have in the future an increasingly active role in the consumers choice. References Beatty, S., Ferrel, E. 1998. “Impulse Buying: Modeling Its Precursors”, Journal of Retailing, 72(0022-4359). Bell. D., Corsten. D., Knox, D. 2011. “From Point of Purchase to Path to Purchase: How Preshopping Factors Drive Unplanned Buying”, Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 31-45. Chandon, P., Hutchinson, J. W., Young, S.H. 2002. “Unseen is unsold: Assessing visual equity with commercial eye-tracking data”, Insead working paper no. 2002/85/MKT. Chandon, P., Hutchinson, J.W., Bradlow, E.T., Young, S.H. 2007. “Measuring the Value of Point-of Purchase Marketing with Commercial Eye-Tracking Data”, Insead–Wharton School Alliance Center for Global Research and Development Working Paper. Fontainebleau. Deloitte Research 2007, Shopper Marketing: capturing a shopper’s mind, heart and wallet, New York: Deloitte Development, PLC Dulsrud, A., Jacobsen, E. 2009. “In-store Marketing as a Mode of Discipline”, Journal of Consumer Policy, 32(3), 203-218. ECR Europe 2011, The Consumer and Shopper Journey Framework. ECR Europe. GMA/Deloitte 2007, Shopper Marketing: Capturing a Shopper's Heart, Mind and Wallet. Washington: The Grocery Manufacturers Association. GMA/Deloitte 2008, Delivering the Promise of Shopper Marketing: Mastering Execution for Competitive Advantage. Washington: The Grocery Manufacturers Association. GMA 2010, Shopper Marketing 3.0, Washington, DC Proceedings of 30th International Business Research Conference 20 - 22 April 2015, Flora Grand Hotel, Dubai, UAE, ISBN: 978-1-922069-74-0 Harris, B. 2010, “Bringing shopper into category management”, in M. Stahlberg & V. Maila (Eds.) Shopper Marketing: how to increase purchase decisions at the point of sale (pp. 28-32). Kogan Page. IGD 2012, Shopper Vista 2012 Inman, J.J., Winer, R.S., Ferraro, R. 2004. Where the Rubber Meets the Road: A Model of In-Store Consumer Decision-Making. Marketing Science Institute. Inman, J.J., Winer, R.S., Ferraro, R. 2009. “The Interplay Among Category Characteristics, Customer Characteristics, and Customer Activities on In-Store Decision Making”, Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 19-29. Kahn, B., Schmittlein, D. 1989. “Shopping trip behavior: An empirical investigation” Marketing Letters, 1(1), 55-69. Larson, J.S., Bradlow, E.T., Fader, P.S. 2005. “An exploratory look at supermarket shopping paths”, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 22(4), 395-414. Larson, J.S., Bradlow, E.T., Fader, P.S. 2006. “How do shoppers really shop?”, International Commerce Review: ECR Journal, 6(1), 56-63. Mohan, G., Sivakumaran, B., Sharma, P. 2013. “Impact of store environment on impulse buying behavior”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 47 No. 10, pp. 1711-1732. Neff, J. 2008. “Pick a product: 40% of public decide in store”, Advertising Age, 79, 31. Oxford Strategic Marketing 2008, The Journey to Strategic Shopper Marketing - Top Ten Findings of a Survey Conducted on Behalf of ECR Europe, Oxford Strategic Marketing. Retail Commission on Shopper Marketing 2010, Shopper Marketing Best Practices: A Collaborative Model for Retailers and Manufacturers, In-Store Marketing Institute. Shankar. V., Balasubramanian, S. 2009. “Mobile Marketing: a synthesis and prognosis”, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23 (2), 118-29, Tenth Anniversary Special Issue. Shankar. V., Venkatesh. A., Hofacker. C., Naik. P. 2010. “Mobile Marketing in the Retailing Environment: current insights and future research avenues”, Journal of Interactive Marketing, 24 (2), 111-20. Shankar, V., Inman, J., Mantrala, M., Kelley, E., Rizley, R. 2011. “Innovations in shopper marketing: current insights and future research issues”, Journal of Retailing, 87S (1,2011), S29-S42. Shankar, V. 2011, Shopper Marketing, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Marketing Science Institute. Shankar, V. 2014. “Shopper Marketing 2.0: Opportunities and Challenges”, Review of Marketing Research, v. 11. Silveria, P., Marreiros, C. 2014. “Shopper Marketing: A Literature Review”, International Review of Management and Marketing, Vol. 4, No. 1, 2014, pp.9097. Sinha, P., Uniyal, D. 2005. “Using observational research for behavioural segmentation”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 12, 35–48. Stilley, K., Jeffrey, J., Inman, Kirk, L. Wakefiled 2010. “Spending on the fly: mental budgets, promotions and spending behaviour”, Journal of Marketing, 74 (3), 3447. U.S. Grocery Shopper Trends 2012 Suher, J., Sorensen, H. 2010. “The Power of Atlas: Why In-Store Shopping Behavior Matters”, Journal of Advertising Research, 50(1), 21-29.