Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference

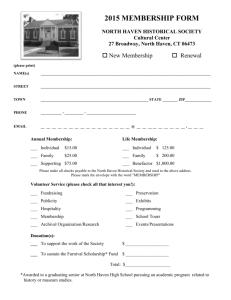

advertisement

Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Hedging Characteristics of Commodity Investment in the Emerging Markets Mitchell Ratner* and Chih-Chieh (Jason) Chiu** Investors derive the greatest risk reduction benefit from portfolio diversification by holding assets with a low co-movement. As correlations between stocks worldwide have been increasing over time, interest in alternative assets such as commodities is also rising. This study examines the risk reducing properties of commodity investment from the perspective of 10 emerging markets from January 1991 through December 2013. Tests of GARCH dynamic conditional correlation coefficients indicate that commodities are portfolio diversifiers, but do not provide a significant long-term hedge. In times of extreme stock market volatility commodities provide a weak safe haven against risk in most countries. During the 1994-95 Mexican peso crisis, the 1997-98 Asian currency crisis, and the 9/11/01 attack, commodities demonstrate significant safe haven properties. However, commodities do not offer significant risk reduction in the 2008 global financial crisis. JEL Codes: G11, G15 1. Introduction Imperfect correlation among investments is the foundation of most asset allocation strategies. The potential benefit of portfolio diversification motivates investors to identify assets that have relatively low correlation with stocks. As global markets continue to converge, investors continue to seek out alternative assets to enhance diversification. Commodities are often considered assets that move with relative independence from stocks. In addition to diversification benefits, commodity holdings can serve as stand-alone investments. Derivative contracts on commodities, long the domain of hedgers and speculators, are now easy to purchase as commodity-based mutual funds, exchange traded funds (ETFs), and exchange traded notes (ETNs). The purpose of this research is to investigate the hedging properties of broad based commodity investment on emerging market stock risk. Similar studies use time varying methodology to investigate individual commodities such as gold and oil, and are largely restricted to developed financial markets (e.g., U.S., U.K.). This study complements and expands the prior literature by focusing on the emerging markets. The portfolio benefits of investing in commodities are assessed in three ways: as a diversifier, as a hedge, and as a safe haven. *Dr. Mitchell Ratner, Department of Finance and Economics, Rider University, USA. Email: ratner@rider.edu **Dr. Chih-Chieh (Jason) Chiu, Department of Finance and Economics, Rider University, USA. Email: cchiu@rider.edu 1 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Following Baur and Lucey (2010), a diversifier is an asset with positive, but imperfect correlation with stock prices. A hedge is defined as an asset that is consistently uncorrelated or negatively correlated to stock price movements. A safe haven is an asset that is consistently uncorrelated or negatively correlated to stock price movements during times of market turmoil. There are three main findings presented in this study. First, commodities are a consistent portfolio diversifier as evidenced by significant but relatively low positive correlations between commodities and stocks in all market indexes. As such, commodities do not serve as a long-term hedge against stock risk in any market. Second, in times of extreme stock market volatility, commodities are generally a weak safe haven in most countries (there are three instances of a strong safe haven). Third, commodities largely provide a strong safe haven against stock risk in most countries during the Mexican peso crisis, the Asian currency crisis, and the 9/11/01 period. During the 2008 global financial crisis, commodities do not provide a safe haven. The remainder of this article is presented as follows. Section 2 provides a review of the literature on commodity investment and studies of safe haven assets. Section 3 describes the data in detail, and the relationship between the commodities and stock market indexes of each country. Section 4 provides the methodology and specification of the models used. Section 5 contains the empirical findings. Section 6 summarizes and concludes the study. 2. Literature Factors influencing commodity price movements may include inflation, productivity, supply and demand, world events (e.g., terrorism), and speculation. Aggarwal and Soenen (1988) suggest that gold can be used as a defensive asset. Chua et al. (1990) find that gold is useful as a portfolio investment asset with U.S. equities. The authors find that the correlation between gold and U.S. equities is increasing over time, and speculate that the benefit of holding gold may diminish if the correlation continues to increase. Faugère and Van Erlach (2005) find that the inverse relationship between gold and other assets provides an effective hedge. Hillier et al. (2006) find that gold and other precious metals have potential diversification benefits, hedging capability, and enhance the performance of equity portfolios. Geman et al. (2008) conclude that the diversification benefits of investment in oil futures contracts arise from their negative correlation with equities. Numerous recent studies examine commodities as an asset class. Akey (2006) demonstrate the benefits of commodities as both stand-alone investments and as diversifiers. Akey (2006) finds that active trading in commodities provides superior returns over passive investment. Erb and Harvey (2006) conclude that individual commodities futures, on average, provide returns that are not statistically different than zero. However, a portfolio of commodities futures contracts might offer positive returns and risk reduction properties. Gorton and Rouwenhorst (2006) construct an equally weighted portfolio of commodity futures from 1959-2004. They discover that a portfolio of commodities has roughly the same return and risk premium as that of an equity portfolio. The Gorton and Rouwenhorst (2006) commodity index is negatively correlated with equities during the test period, which provides evidence that commodities are useful as a hedge. Ebens et al. (2009) develop an asset allocation strategy and demonstrate that investing in commodities improves portfolio performance. Conover, et al. (2010) examine the long-term portfolio benefits of investing in the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index using both tactical and strategic methodology. They find substantial benefits from commodities investment regardless of the investment style. Nguyen and Sercu (2011) develop a tactical asset allocation model for trading commodities based on business cycles and monetary policy. The authors find that 2 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 strategic trading in commodities can be beneficial, but underperforms a buy-and-hold strategy. Further, the authors add that even the diversification benefits demonstrated by prior studies may be overstated. The authors conclude that commodities investment should be limited to only a small part of an investment portfolio. The ongoing interest in commodities by the investment community, combined with the apparent debate in the literature, justifies further analysis of this topic. The interest in identifying effective hedge and safe haven assets is growing for two related reasons. First, rising correlations among country stock markets over time diminish the advantages of international portfolio diversification (Eun and Lee, 2010). Second, the contagion literature shows that there is excessive interdependence between stock markets during the 1987 U.S. stock market crisis, the 1994 Mexican Peso crisis, and the 1997 Asian crisis, and that global crashes are preceded by local and regional crashes as a domino effect (Forbes and Rigobon, 2002 and Markwat et al., 2009). Empirical studies examine the role of gold as an alternative asset for hedging against stock risk. Bauer and Lucey (2010) use time-varying betas to demonstrate the usefulness of gold as a hedge and safe haven against stock risk in the U.S., U.K., and Germany. Using a related methodology, Bauer and McDermott (2010) identify the hedging and safe haven properties of gold against stock risk in a sample of developed and emerging countries. The role of oil as a non-financial commodity is also investigated as a hedge against stock risk due to its importance to the world economy. Studies generally find a positive relationship between oil and equity returns, but the nature of causality is varied and uncertain (Apergis and Miller, 2009, and Park and Ratti, 2008). More recently, Ciner (2013) finds that both gold and oil are not safe havens against equity risk in the U.S. and U.K., but they do offer some protection against currency risk. 3. The Data As investors cannot directly purchase a commodity index, selection of an appropriate proxy, such as a derivative contract, ETF, ETN, or mutual fund, is required. The two most popular commodity indexes (serving as ETF/ETN benchmarks) are the Standard & Poor‟s Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) and the Dow Jones-UBS Commodity Index (DJ-UBS). (In May 2009, UBS GA purchased the commodities business of AIG Inc. The DJ-AIG Commodity Index has been renamed the Dow Jones-UBS Commodity Index.) As Akey (2006) notes, the DJ-UBS is considered the benchmark for a diversified group of commodities, while the GSCI is heavily weighted by its position in energy futures contracts. We document a correlation of 0.90 between the GSCI and DJ-UBS from 1991-2013. This study employs the DJ-UBS to represent a broad commodity investment. The DJ-UBS currently represents futures contracts on 19 physical commodities traded on U.S. markets, with the exception of aluminum, nickel, and zinc that trade on the London Metals Exchange. To achieve diversification, related groups of commodities (e.g., energy, livestock, etc.) are limited to no more than 33% of the index. Additionally, no individual commodity may contribute less than 2% or more than 15% of the index after reweighting. The DJ-UBS maintains a long position by selling contracts that will expire and purchasing new contracts on the same underlying asset (known as “rolling” a futures position). This process creates a problem with commodities investments called “contango” that results from a price 3 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 differential between the more expensive new contracts purchased and the less expensive older contracts sold. Since commodity index spot prices consistently overstate returns, this study utilizes the total returns of the commodity indexes to accurately measure the investor‟s actual return (comparable to including dividend reinvestment when analyzing stock returns). The sample period for the study is from January 1991 through December 2013, corresponding to the creation of the DJ-UBS in January 1991. Local returns represent the perspective of the emerging markets and avoid the distortion of converting returns into U.S. dollars. Equity market performance is based on the Datastream Total Stock Market Index for each country. Stock index prices are the total return indexes including dividends. Selection of the sample countries is based on the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. MSCI currently identifies 21 countries as emerging markets. Due to the time period studied and the absence of a sufficient sample size, we select the 10 largest markets in the MSCI index including: Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Taiwan. Table 1 Descriptive statistics for stock market data and the DJ-UBS Standard # of Mean Deviation Min Max JarqueMarket Observ. (%) (%) (%) (%) Bera Brazil 1017 0.375*** 3.834 -22.473 25.715 859*** China 1066 0.344** 5.111 -31.095 37.300 2044*** India 1199 0.369*** 4.228 -22.812 29.343 1539*** Indonesia 1199 0.311** 4.407 -21.752 31.319 2164*** Korea 1199 0.264** 4.378 -19.948 22.968 466*** Malaysia 1199 0.238** 3.479 -16.159 44.177 4516*** Mexico 1199 0.443*** 3.333 -16.209 17.689 478*** Russia 830 0.636** 6.485 -33.243 53.616 4124*** S. Africa 1199 0.346*** 2.855 -18.115 13.803 984*** Taiwan 1199 0.187*** 3.814 -16.566 16.003 199*** DJ-UBS 1199 0.098* 2.058 -9.936 7.047 211*** Note: *** and ** indicates significance at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. Weekly data for all variables in this study are measured from Wednesday-to-Wednesday close. To achieve stationarity, all indexes are transformed into first-difference form. Daily data suffers from non-synchronous trading between commodity prices (set in the U.S. time zone) and local emerging equity markets. Monthly data frequency is too low to capture significant time variation effects between the variables. Descriptive statistics for the stock indexes and the DJ-UBS are provided in Table 1. Weekly mean stock returns are all significantly positive during the sample period. The highest mean appears in Russia (0.636%) and lowest in Taiwan (0.187%). Standard deviation in stock returns is highest in Russia (6.485%) and lowest in South Africa (2.855%). By contrast, the mean return of the DJ-UBS is 0.098% with a standard deviation of 2.058%. The Jarque-Bera test for normality is rejected at the 1% level for all variables, supporting the use of GARCH analysis. Due to the absence of available data, observations in Brazil, China, and Russia start later than 1991. 4 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Fig. 1. Commodity and stock market levels. stock ------ commodity Figure 1 provides a graph for each emerging market stock index against the DJ-UBS in nondifferenced form. All stock indexes appear to be positively correlated with the DJ-UBS, rise prior to the global financial crisis period of 2007-2009, decline during the crisis period, and begin to experience a noticeable recovery in 2009. In contrast, the DJ-UBS has not recovered its pre-crisis level compared with the stock indexes. Korea, Malaysia, and most notably Taiwan experience more significant volatility in the Asian crisis period starting in 1997. 4. Methodology Dynamic conditional correlation (DCC) is a technique developed by Engle (2002) to examine timevarying correlation. In contrast to a constant correlation model, the time-varying nature of the technique allows correlations to be positive, negative, or zero. The procedure uses GARCH to generate time-varying estimates of the conditional co-movement between assets implemented as: 5 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 rt |It-1 N(0 Ht ) Ht t t t (1) (2) where rt is the k x 1 demeaned vector of variables conditional on information I t-1, and is assumed to be conditionally multivariate normal. Ht is the covariance matrix where t is the k x k timevarying correlation matrix, and Dt is the k x k diagonal matrix of conditional standardized residuals estimated from the univariate GARCH models. The general form equation of the likelihood function of the estimator is given by: -0.5 ∑Tt 1 (klog(2 ) 2log(| t |) log(| t |) ́ t -1 ) t t (3) There are two variable steps in this procedure. The volatility component D t is maximized in the first step by replacing t with a k x k identity matrix. This results in reducing the log likelihood to the sums of the log likelihoods of the univariate GARCH equations. The first order univariate GARCH models are estimated for the DJ-UBS and stock indexes of each country using the Glosten et al. (1993) model allowing for asymmetries: ht c0 a1 2 t-1 b1 ht-1 d1 2 I t-1 t-1 (4) where ht is the conditional variance, d1 is the asymmetry term, and It-1=1 if t<0, otherwise I=0. The correlation component t is maximized in the second step: t (1- - )̅ t-1 ́ t-1 (5) t-1 where the values of the DCC parameters and are provided. If and are zero then reduces to ̅, which would indicate that the constant correlation model is appropriate. t Following the GARCH estimation the time varying correlations t are extracted from model (5) into a separate time series for each country. t are regressed on dummy variables representing market turmoil to test the DJ-UBS as a hedge, safe haven, or diversifier against stock risk: t 0 1 (rstock q10 ) 2 (rstock q5 ) 3 (rstock q1 ) (6) where D represent dummy variables that capture extreme movements in the underlying stock index at the 10%, 5%, and 1% quantiles of the most negative stock returns. The DJ-UBS is a weak hedge if 0 is insignificantly different than zero, a strong hedge if 0 is significantly negative, or a diversifier if 0 is significantly positive. The DJ-UBS is a weak safe haven if the 1, 2, or 3 coefficients are insignificantly different than zero or a strong safe haven if they are significantly negative. Significantly positive 1, 2, or 3 coefficients indicate that the DJ-UBS is not a safe haven during periods of extreme stock volatility. To examine the DJ-UBS as a hedge, safe haven, or diversifier against stock risk during a period of crisis, a modified version of a dummy variable regression model used by Baur and McDermott (2010) is empirically tested as: t 0 1 ( exico) 2 (Asia) 3 ( /11) 4 (Global) (7) 6 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 where a dummy variable is set to one (for 20 trading observations) following the start of four periods of crisis: Mexican peso crisis (12/19/1994), Asian currency crisis (10/20/97), 9/11 attack, and the global financial crisis (9/10/08). The DJ-UBS is a weak hedge if 0 is insignificantly different than zero a strong hedge if 0 is significantly negative or a diversifier if 0 is significantly positive. The DJ-UBS is a weak safe haven in specific crisis periods if the 1, 2, 3, 4 coefficients are insignificantly different than zero or a strong safe haven if they are significantly negative. Significantly positive 1, 2, 3, 4 coefficients indicate that the DJ-UBS is not a safe haven during the specific crisis period. 5. Empirical results Estimation results of the GARCH models for the DJ-UBS and stock indexes are provided in Table 2. The univariate GARCH parameters (c0, a1, b1, d1) show that most coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% or 5% levels across most countries. The significant positive asymmetry term d1 implies that declines in stock indexes are followed by a reduction in volatility. The high degree of significance among the GARCH parameters indicates both time variation and dependence in the variance, which supports the use of GARCH-DCC models. The estimates of the CC parameters and are statistically significant and their sum is close to one for most countries. This indicates that the volatility process is stable and that there is a high degree of persistence. All of the coefficients are significant at the 1% level, further supporting the use of a time varying model as opposed to a constant correlation model. The time series of the dynamic conditional correlation coefficients ( t) between the DJ-UBS and stock indexes for each country are extracted from the GARCH model and graphed in Figure 2. The signs of the correlation coefficients are mostly positive for all countries. In a static sense this indicates that increases in DJ-UBS are associated with increases in stock indexes. This relationship indicates that commodities are more likely a portfolio diversifier rather than a hedge. However, the magnitude and variability of the coefficients is unique to each country. Relatively brief periods of negative correlation coefficients are observed in all countries except Russia. The most consistently negative DCC coefficients occur in Taiwan. Negative coefficients imply a portfolio hedge and possible safe haven. Lastly, correlation coefficients appear to be generally highest in all countries during the global financial crisis period. As such, the DJ-UBS does not appear to be an effective hedge or diversifying asset during the global crisis. 7 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Table 2 Univariate GARCH estimates for stock index returns and the Dow Jones UBS commodity index. Brazil China India Indonesia Korea c0,commodity 0.000** 0.000** 0.000** 0.000** 0.000** a1,commodity 0.062*** 0.062*** 0.062*** 0.062*** 0.062*** b1commodity 0.940*** 0.940*** 0.940*** 0.940*** 0.940*** d1commodity -0.015 -0.015 -0.015 -0.015 -0.015 c0stock 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000 a1stock 0.076*** 0.101*** 0.128*** 0.050*** 0.073*** b1stock 0.842*** 0.850*** 0.870*** 0.864*** 0.869*** d1stock 0.095*** 0.057** -0.021 0.133*** 0.092*** 0.842*** 0.850*** 0.870* 0.864*** 0.869** 0.095*** 0.057*** -0.021*** 0.133*** 0.092*** Malaysia Mexico Russia S. Africa Taiwan c0,commodity 0.000** 0.000** 0.000** 0.000** 0.000** a1,commodity 0.062*** 0.062*** 0.062*** 0.062*** 0.062*** b1commodity 0.940*** 0.940*** 0.940*** 0.940*** 0.940*** d1commodity -0.015 -0.015 -0.015 -0.015 -0.015 c0stock 0.000*** 0.000*** 0.000** 0.000*** 0.000*** a1stock 0.086*** 0.061*** 0.056* 0.023*** 0.058*** b1stock 0.880*** 0.880*** 0.912*** 0.871*** 0.901*** d1stock 0.067*** 0.096*** 0.050** 0.136*** 0.053*** 0.880** 0.880*** 0.912*** 0.871*** 0.901*** 0.067*** 0.096*** 0.050*** 0.136*** 0.053*** Note: ***,**,* indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. Models: ht c0 a1 2t-1 b1 ht-1 d1 2t-1 It-1 and t (1- - )̅ t-1 ́ t-1 t-1 Two models test the DJ-UBS as a hedge and safe haven against stock risk based on a similar methodology used by Baur and McDermott (2010). The first model examines the hedging and safe haven characteristics of the DJ-UBS during periods of extreme stock market volatility. The second model focuses on the hedging and safe haven properties of the DJ-UBS during periods of crisis. 8 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 Fig. 2. GARCH-DCC estimates for commodities and stocks. Table 3 shows the estimates of regressions from model (6). The CC coefficients t are regressed on a constant and three dummy variables representing levels of extreme stock volatility quantiles of 10%, 5%, and 1% of the most negative stock returns in each country‟s stock index. The “hedge” column represents the model constant 0, which shows a positive relationship between the DJUBS and stock index of each country with significance at the 1% level. A significantly positive value indicates that the DJ-UBS is a diversifier asset to the stock index, but not a hedge. While significant diversification properties are demonstrated across all countries, the benefits of the DJ- 9 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 UBS vary among markets. A smaller coefficient value provides the greatest benefit, i.e., the DJUBS provides a larger benefit in Taiwan (0.129) compared with a lower benefit in Russia (0.344). The stock quantile regression coefficients ( 1 2 3) represent the safe haven characteristics of the DJ-UBS against extreme negative stock risk. Negative and significant coefficients indicate that the DJ-UBS is a strong safe haven within the 5% stock quantile in Brazil (-0.105), and in the 10% quantile for Russia (-0.052) and Taiwan (-0.057). The insignificant regression coefficients for all remaining variables indicate that the DJ-UBS serves as a weak safe haven – the DJ-UBS reduces risk during periods of extreme volatility in the stock market. Table 3 The DJ-UBS as a hedge and safe haven against stock risk during extreme stock volatility. Stock Quantile Hedge 10% 5% 1% Market ( 0) ( 1) ( 2) ( 3) Brazil 0.281*** 0.020 -0.105*** -0.011 China 0.227*** 0.010 0.025 0.009 India 0.144*** -0.005 -0.005 -0.044 Indonesia 0.147*** -0.015 0.028 -0.018 Korea 0.166*** -0.029 -0.042 -0.010 Malaysia 0.157*** -0.016 0.022 0.050 Mexico 0.187*** -0.026 0.007 -0.015 Russia 0.344*** -0.052** 0.044 0.038 S. Africa 0.276*** -0.006 0.015 0.027 Taiwan 0.129*** -0.057** -0.003 0.018 Note: ***,**,* indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. Model: t 0 1 (rstock q10 ) 2 (rstock q5 ) 3 (rstock q1 ) The second model tests the DJ-UBS as a hedge and safe haven during the periods of crisis based on model (7). The results presented in Table 4 show a positive relationship between the DJ-UBS and the stock indexes in the model constant 0 with significance at the 1% level. This suggests that the DJ-UBS is a strong diversifier against stock risk as the correlations are relatively low. The benefit of the DJ-UBS as a safe haven asset appears to change over time. During the Mexican peso crisis, significantly negative coefficients indicate that the DJ-UBS is a strong safe haven in all countries at the 1% level, except for South Africa (insignificant 1 coefficients suggest that the DJUBS is a weak safe haven in South Africa). During the Asian currency crisis, the DJ-UBS provides a strong safe haven in Brazil, India, Korea, Mexico, South Africa, and Taiwan, and a weak safe haven in China, Indonesia, and Malaysia. A significantly positive coefficient shows that the DJ-UBS is not a safe haven in Russia. Following the 9/11 attack in New York, the DJ-UBS is a strong safe haven in all countries with two exceptions: it is only a weak safe haven in South Africa, and is not a safe haven in India (due to the significantly positive coefficient). The results during the global financial crisis indicate that the DJ-UBS does not provide a safe haven in any country except Korea, where it is a weak safe haven. We speculate that the failure of the DJ-UBS to provide a safe haven is likely due to the catastrophic nature (systemic risk) of this event reflected in most financial marketplaces (e.g., stocks, bonds, derivatives, commercial paper, 10 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 etc.). Systemic risk is the risk of financial system failure that could lead to disruptions or even collapse of the real economy. Table 4 The DJ-UBS as a hedge and safe haven against stock risk during crises. Crisis Period Hedge Mexico Asia 9/11 Global Market ( 0) ( 1) ( 2) ( 3) ( 4) Brazil 0.284*** -0.183*** -0.196*** -0.139*** 0.284*** China 0.238*** -0.117*** -0.062 -0.369*** 0.238*** India 0.147*** -0.115*** -0.085*** 0.078** 0.147*** Indonesia 0.147*** -0.110*** 0.010 -0.150*** 0.147*** Korea 0.171*** -0.140*** -0.252*** -0.217*** 0.171 Malaysia 0.160*** -0.114*** 0.033 -0.167*** 0.160*** Mexico 0.190*** -0.171*** -0.168*** -0.083** 0.190*** Russia 0.344*** NA 0.155* -0.247*** 0.344*** S. Africa 0.277*** -0.041 -0.120*** -0.023 0.277*** Taiwan 0.129*** -0.205*** -0.111*** -0.081** 0.129* Note: ***,**,* indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. Model: t 0 1 ( exico) 2 (Asia) 3 ( /11) 4 (Global) 6. Summary and Conclusion Due to the increasing attention on investment in alternative assets, this paper explores the risk reducing benefits of commodities from the perspective of emerging markets investors. While the literature documents the use of gold and other specific commodities as hedging instruments against stock risk, there is little attention given to the hedging role of broad based commodity investment, especially from the perspective of the emerging markets. Specifically, this study adds to the literature by evaluating the hedging characteristics of the Dow Jones-UBS commodity index against stock market risk in 10 emerging markets from 1991 through 2013. Empirical analysis utilizes GARCH dynamic conditional correlation (DCC) to examine the time varying relationship between the DJ-UBS and stock market indexes. The major findings are as follows: First, during periods of extreme negative stock market volatility, the DJ-UBS demonstrates strong diversification characteristics against stock risk, but it is not an effective hedge in any country. Second, regression analysis shows that the DJ-UBS is largely a weak safe haven against stock risk during times of extreme negative stock volatility. Third, the DJ-UBS is generally a strong safe haven during the Mexican peso crisis, the Asian currency crisis, and the period following the 9/11/2001 attack. However, similar to many other assets, the DJ-UBS does not provide a safe haven during the recent global financial crisis. 11 Proceedings of 3rd Global Business and Finance Research Conference 9 - 10 October 2014, Howard Civil Service International House, Taipei, Taiwan, ISBN: 978-1-922069-61-0 References Aggarwal, R & Soenen L 1988, „The Nature and Efficiency of the Gold Market‟ Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 14, pp. 18-21. Akey, R 2006, „Alpha, Beta and Commodities: Can a Commodities Investment Be Both a High Risk-Adjusted Return Source, and a Portfolio Hedge?‟ The Journal of Wealth Management, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 63-86. Apergis, N & Miller, S 2009, „Do structural oil-market shocks affect stock prices?‟ Energy Economics, vol. 31, pp. 569–575. Baur, D & Lucey, B 2010, „Is Gold a Hedge or a Safe Haven? An Analysis of Stocks, Bonds and Gold‟ The Financial Review, vol. 45, pp. 217–229. Baur, D & McDermott T 2010, „Is gold a safe haven? International evidence‟. Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 34, pp. 1886–1898. Ciner, C, Gurdgiev, C, & Lucey, B 2013, „Hedges and safe havens: An examination of stocks, bonds, gold, oil and exchange rates‟, International Review of Financial Analysis, vol. 29, pp. 202-211. Conover, C, Jensen, G, Johnson R, & Mercer, J 2010, „Is Now the Time to Add Commodities to Your Portfolio?‟ Journal of Investing, vol. 19, pp. 10-19. Chua, J, Sick, G, & Woodward R 1990, „Diversifying with Gold Stocks‟, Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 46, pp. 76-79. Ebens, H, Kotecha, C, Ypsilanti, A, & Reiss, A 2009, „Introducing the Multi-Asset Strategy Index‟, The Journal of Alternative Investments, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 6-27. Engle, R 2002, „Dynamic Conditional Correlation - A Simple Class of Multivariate GARCH‟ Journal of Business & Economics Statistics, vol. 20, pp. 339–50. Erb, C & Harvey, C 2006, „The Strategic and Tactical Value of Commodity Futures‟ Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 69-97. Eun, C & Lee, J 2010, „Mean-variance convergence around the world‟, Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 34, pp. 856-870. Faugère, C & Van Erlach, J 2005, „The Price of Gold: A Global Required Yield Theory‟. Journal of Investing, vol. 14, pp. 99-112. Forbes, K & Rigobon, R 2002, „No contagion, only interdependence‟, Journal of Finance, vol. 57, pp. 2223–2261. Geman, H & Kharoubi C 2008, „WTI crude oil Futures in portfolio diversification: The time-tomaturity effect‟ Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 3212, pp. 2553-59. Gorton, G & Rouwenhorst G 2006, „Facts and Fantasies about Commodity Futures‟ Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 622, pp. 47-69. Glosten, L, Jagannathan, R & Runkle D 1993, „On the relation between the expected value and the volatility of the nominal excess return on stocks‟ Journal of Finance, vol. 485, pp. 1779– 1801. Hillier, D, Draper, P & Faff, R 2006, „Do Precious Metals Shine? An Investment Perspective‟ Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 62, pp. 98-106. Markwat, T, Kole, E, & Van Dijk, D 2009, „Contagion as a domino effect in global stock markets‟ Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 33, pp.1996-2012. Nguyen, V & Sercu, P 2011, „Tactical Asset Allocation with Commodity Futures: Implications of Business Cycle and Monetary Policy‟ SSRN research paper. Park, J & Ratti, R 2008, „Oil price shocks and stock markets in the US and 13 European countries‟ Energy Economics, vol. 30, pp. 2587–2608. 12