“We Buy Houses”: A Foreclosure Rescue as Equity Problem

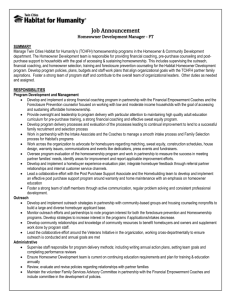

advertisement