Transfer by the Mortgagee Chapter

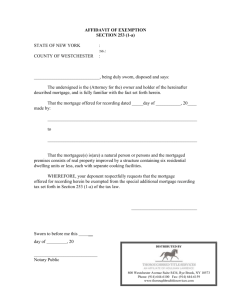

advertisement