Outdated Publication, for historical use.

CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete.

Weigh to Diet

Barbara Lohse, Ph.D., R.D.

Kansas State University

Modern dictionaries define diet as: 1) food and drink regularly provided or consumed,

2) something used, enjoyed, or provided

regularly, or 3) national or local legislative

assemblies. However, a look at the root word

for diet suggests that the word means much

more. Diet is from the Latin diaeta or Greek

diaita, meaning manner or way of living.

Study of weight management issues has

shown our manner of living or lifestyle to be important. Physical activity, stress

management, dining style, and biology stand

with food intake as key influences on weight.

This lesson focuses on weight through these

lifestyle influences, also known as your diet.

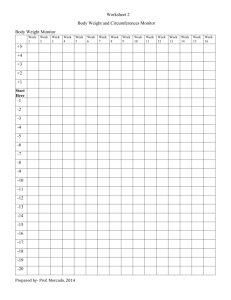

A. Body Measures

Experts have identified two measures that

are important to know: the body mass index

(BMI) and waist circumference. BMI is determined from a mathematical

formula that compares your weight to your

height. Not fond of math? Use the table on the

next page to find your BMI. You can also go

to www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi and enter your

height and weight into the BMI calculator.

Voila! Your BMI is calculated. The goal is

to have a BMI between 18.5 and 25. A BMI

between 25 and 30 is considered overweight,

and obesity is defined as a BMI higher than

30. The BMI is not a useful measure of healthy

weight for persons who are very muscular. For BMIs between 25 and 35, waist

circumference can help warn of increasing

fatness. Place a flexible tape around yourself so it is level with the top of your hip bones

(approximately at the navel). Be sure to read the tape after exhaling. Measurements of more

than 35 inches for women and 40 inches for

men signal a need to reflect on your overall

health, then review eating and exercise habits.

B. Healthy Weight

Defining "healthy weight" is difficult

because weight status reflects disease, body

composition, age, and health-related behaviors

such as smoking. Identifying a healthy weight

Kansas State University

Agricultural Experiment

Station and Cooperative

Extension Service

as one associated with fewer deaths is the basis

for most height-weight tables. We know that,

in addition to weight, amount of body fat,

location of body fat, undetected disease such

as cancer, level of physical and mental fitness,

and tobacco use influence mortality.

Known risk factors that can exist with

excess weight are high blood pressure, high

cholesterol, high blood sugar, and a family

history of heart disease. These factors confuse

the relationship between weight and mortality.

As a result, determining your healthy weight

may require help from a health professional.

A person who is overweight but has a normal

waist circumference and only one risk

factor has a different healthy weight than

an overweight person with a large waist

circumference and three risk factors.

Likewise, the healthy weight for a person

with a BMI greater than 30, a high waist

circumference, and no health problems will

differ from an obese person with several health

problems. Although BMI, waist circumference,

and health are important factors, a healthy

weight depends on your individual profile.

Achieving a healthy weight if you are

overweight by BMI or waist circumference

standards does not mean a need to be at the

ideal weight. For many, the loss of only 5 to 10 percent of body weight will significantly

decrease risk of disease. Another marker is to

just decrease BMI by one unit. A new approach to defining a healthy

weight is to focus on “Health at Any Size”

according to Frances Berg in Children and

Teens, Afraid to Eat (2001, Healthy Weight

Network). Rather than dieting for weight

loss, the goal is to achieve well-being through

eating, physical activity, and self-acceptance.

HUGS (www.hugs.com) is an adult weight

management program with a Health focus,

centered on Understanding lifestyle behaviors,

Group support, and Self-esteem building.

Ellyn Satter has linked emotional health

and eating behavior in a concept called Eating

Outdated Publication, for historical use.

CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete.

BMI

Height 4’10” (58”)91

4’11” (59”)94

5’ (60”) 5’1” (61”) 5’2” (62”) 5’3” (63”) 5’4” (64”) 5’ 5”(65”) 5’6” (66”) 5’7” (67”) 5’ 8”(68”) 5’ 9”(69”) 5’ 10”(70”)

5’ 11”(71”)

6’(72”) 6’ 1”(73”) 6’ 2”(74”) 6’ 3”(75”) 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35

Weight (in pounds)

96

99

97

100

104

107

110

114

118

121

125

128

132

136

140

144

148

152

100

104

102

106

109

113

116

120

124

127

131

135

139

143

147

151

155

160

105

109

107

111

115

118

122

126

130

134

138

142

146

150

154

159

163

168

110

114

112

116

120

124

128

132

136

140

144

149

153

157

162

166

171

176

115

119

118

122

126

130

134

138

142

146

151

155

160

165

169

174

179

184

119

124

123

127

131

135

140

144

148

153

158

162

167

172

177

182

186

192

124

128

128

132

136

141

145

150

155

159

164

169

174

179

184

189

194

200

129

133

133

137

142

146

151

156

161

166

171

176

181

186

191

197

202

208

134

138

138

143

147

152

157

162

167

172

177

182

188

193

199

204

210

216

138

143

143

148

153

158

163

168

173

178

184

189

195

200

206

212

218

224

143

148

148

153

158

163

169

174

179

185

190

196

202

208

213

219

225

232

148

153

153

158

164

169

174

180

186

191

197

203

209

215

221

227

233

240

Source: Evidence Report of Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults, 1998.

NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI)

Competence, which is more than trying to lose

or maintain weight or trying to get yourself

to eat only healthy foods. It promotes being

positive and comfortable with eating while

making sure to get enough of enjoyable,

nourishing food. (Secrets of Feeding a Healthy

Family, 1999, Kelcy Press)

To you, what is a healthy weight?

Is yours a healthy weight?

Learn more at: www.hsph.harvard.edu/

nutritionsource/weight.html

C. Dieting

To most people “dieting” commonly means

altering food intake to achieve a weight

goal. After reflecting on your health needs

and a weight goal, a change in your dietary

patterns may be in order. Once you plan to

alter your intake, meal plans promising weight

loss, health, and self-esteem will seem to be

everywhere: Eat only raw food! Wine and

chocolate with each meal! Choosing one that

is right for you will take some study. A “No”

answer to the following questions signals a

better plan. Does the plan . . .

•Promise rapid weight loss?

•Offer testimonials and personal stories as

proof?

•Require laboratory tests before you can start?

•Criticize the medical or scientific community?

•Include many supplements and special

ingredients?

•­­Promise you can eat all you want, especially of

certain “good” foods?

•Ignore your food preferences, lifestyle, or

budget?

153

158

158

164

169

175

180

186

192

198

203

209

216

222

228

235

241

248

158

163

163

169

175

180

186

192

198

204

210

216

222

229

235

242

249

256

162

168

168

174

180

186

192

198

204

211

216

223

229

236

242

250

256

264

168

173

174

180

186

191

197

204

210

217

223

230

236

243

250

257

264

272

179

185

191

197

204

210

216

223

230

236

243

250

258

265

272

279

My BMI is

.

My waist measures

Should I be concerned?

in.

Get additional guidance: www.consumer.gov/

weightloss/index.htm

www.eatright.org/Public/NutritionInformation/

92_nfs0200b.cfm

www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/edcams/fitness/

coninfo.html Even if you can answer “No” to all, select

your plan carefully. For example, a highprotein, low-carbohydrate diet is touted as the

way to lose weight. Does this plan work? Is it

safe? These diets lead to short-term weight

loss because they are low calorie and promote

dehydration. Carbohydrates are stored with

water; a low-carbohydrate diet prompts us to

use these stored carbohydrates, releasing large

amounts of water. Without carbohydrates, we

rely heavily on fat for energy. Using a lot of fat

leads to a condition called ketosis, which can

change electrolytes; leach calcium from bone;

and cause fatigue, nausea, and bad breath.

Metabolizing the high protein intake can harm

kidneys. High-protein diets are high in harmful

saturated fat, low in many vitamins, and – most

important – boring. More studies are needed to

learn about the long-term safety of such plans.

The DASH Eating Plan (Dietary Approaches

to Stop Hypertension), which is much higher

in carbohydrates, has been shown to lower

blood pressure and also may lead to weight

loss and improved cardiac risk factors. The

plan calls for 7 to 8 servings of grains; 4 to 5

vegetables; 4 to 5 fruits; 2 to 3 dairy; 2 meat;

and 4 to 5 nuts, seeds, or beans. Learn more

about the plan, including recipes, from: www.

nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/

heart/hbp/dash/.

Outdated Publication, for historical use.

CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete.

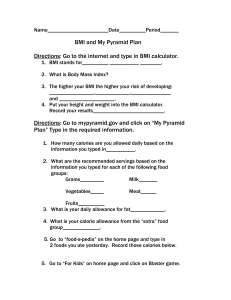

D. Food Guides

A food guide is a tool to translate nutrition

science into a form that can help people choose

healthy eating patterns. Many healthful eating

patterns have been found for humans, and

controversy about nutrition science concepts

have led to the development of several food

guides. A well-known guide is the USDA Food

Guide Pyramid (shown below). E. Appetite Control

Many other food guides and portion size

help can be found on the Mayo Clinic Web page

www.mayoclinic.com under Health Centers:

Food and Nutrition. Two more food guides are

shown below and at the right.

Willett WC, Stampfer M. Rebuilding the Food Pyramid. Scientific

American 288(1):64-71;2003.

Following a food guide promotes a healthy

lifestyle. Think about what you have eaten

today or what you plan to eat.

• Do you think your intake is healthy

according to one of these food guides?

• Which food guide is right for you

to follow?

With fluctuations in daily activity level, food

intake, and health status, it is amazing that

we maintain relatively stable weight. Weight

stability appears to stem from molecular signals

in the body. Appetite-regulating systems are

designed to protect more against weight loss

than weight gain. Appetite controllers show a

tight connection between brain, gut, and fat

cells. In a specific brain region (the arcuate

nucleus), two nerve cell types keep balance. One type of nerve cell produces Neuropeptide

Y (NPY) and Agouti-Related Peptides (AgRP)

that send messages to increase appetite. The

other nerve cell type, known as POMC/CART

releases alpha-Melanocyte Stimulating

Hormone that decreases appetite. What

activates NPY/AgRP and POMC/CART nerve

cells? Many factors, including Leptin, Insulin,

Ghrelin, and PYY.

Leptin—(from Greek, leptos, meaning

thin), a hormone produced in fat cells, leads to

decreased food intake and appears to protect

against weight loss because shrinking fat stores

mean less leptin is available to lower appetite.

Unfortunately, larger fat stores do not produce

leptin levels high enough to decrease appetite

and weight. Obese persons may not respond to

leptin; current studies focus on problems with

leptin receptors. Leptin production is higher in

women and persons recovering from anorexia

nervosa and is activated by a stress hormone.

Insulin—a hormone produced in specific

cells of the pancreas. Insulin suppresses

appetite by inhibiting NPY, the peptide that

stimulates appetite. Appetite and weight are

better controlled when the brain is insulin

sensitive.

Outdated Publication, for historical use.

CAUTION: Recommendations in this publication may be obsolete.

Ghrelin—a short-term appetite regulator

peptide made in the stomach that stimulates

the release of growth hormone. Ghrelin is a

powerful appetite stimulator, peaking an hour

or two before mealtime. Ghrelin levels are

much lower after gastric bypass surgery.

PYY—another short-term regulator that

decreases appetite, helping to end meals.

Marx J. Science 299:846-849; 2003. Myers M. Eating Disorders

Review 13:1-3;2002. Cummings DE et al. NEJM 346:1623-1630;2002.

Food intake decreases because POMC/

CART nerve cells are stimulated by leptin

and insulin. Along with PYY, these hormones

inhibit NPY/AgRP tracts. Food intake is

increased when ghrelin stimulates NPY &

AgRP nerve cells. Both types of nerve cells

target a satiety center in the brain (the

nucleus tractus solitarius), which promotes a

feeling of fullness or gratification. Messages

from the gut and liver are relayed via intestinal

and spinal nerves to the satiety center.

Cholecystokinin is a peptide produced by the

small intestine in response to food digestion. It decreases appetite by

stimulating a specific nerve to signal the

satiety center that food is being digested.

Draw a chart or diagram on a sheet of

paper to summarize appetite control.

F. Be Active and Stretch!

Finally, a healthy way of living must

include physical activity. In addition to

decreasing risk of chronic disease and

overweight, physical activity reduces stress

and anxiety, and enhances mental health,

strength, and balance. Stretching is an ideal

way to initiate a goal of increased physical

activity.

Physical activity is for every body type.

Check the Active at Any Size Web site for ideas

and safety tips: www.niddk.nih.gov/health/

nutrit/activeatanysize/active.html

Nancy Gyurcsik, Ph.D., Department of

Kinesiology at Kansas State University, offers

some answers to these important questions

about stretching:

•Why should I stretch?

To keep your muscles and joints limber so that

you can do all types of activities that you enjoy

but involve your heart working harder than

when you are at rest.

To lower your risk of falling and getting injured.

•How do I stretch? Move slowly into your stretch.

DO NOT jerk into position or bounce when you

stretch.

HOLD the stretch at the point of mild

discomfort.

•Should I feel pain when I stretch?

Absolutely not – you should only feel mild

discomfort.

•How long should I hold a stretch?

Hold each stretch for 15 seconds. Repeat two

times.

•How many times in a week should I

stretch?

Three to seven times.

•What equipment do I need to stretch?

Not much – only a towel and a chair.

Eager to try some stretching exercises? Get

your doctor’s approval, then select exercises

shown on these Web sites.

www.agingwell.state.ny.us/fitness/stretch/index.htm

www.niehs.nih.gov/odhsb/ergoguid/chapiii.htm

nihseniorhealth.gov/exercise/stretchingexercises/

01.html

After stretching, do you feel better ___

more active ___ healthier ___?

Brand names appearing in this publication are for product identification purposes only.

No endorsement is intended, nor is criticism implied of similar products not mentioned.

Publications from Kansas State University are available on the World Wide Web at: http://www.oznet.ksu.edu

Publications from Kansas State University may be freely reproduced for educational purposes. All other rights reserved.

In either case, credit Barbara Lohse, Ph.D. R.D., Weigh to Diet, August 2003.

Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service , Manhattan, Kansas

MF-2595

August 2003

It is the policy of Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service that all persons shall have equal opportunity and access to its

educational programs, services, activities, and materials without regard to race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, or disability. Kansas State University is an equal opportunity

organization. These materials may be available in alternative formats.

Issued in furtherance of Cooperative Extension Work, Acts of May 8 and June 30, 1914, as amended. Kansas State University, County Extension Councils, Extension Districts, and

United States Department of Agriculture Cooperating, Marc A. Johnson, Director.