Document 13273128

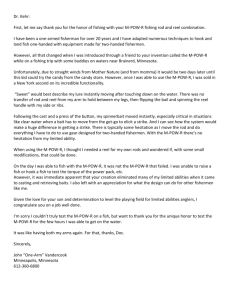

advertisement