Bacteriological Studies on Eggs. Historical Document Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station

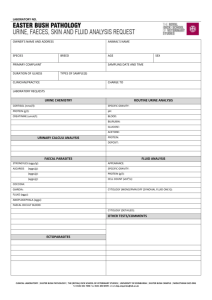

advertisement