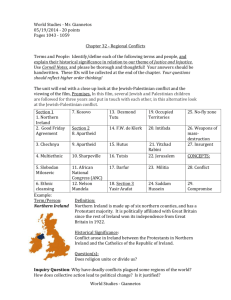

Women Edge? on the The Northern Ireland Economy:

advertisement