EXERCISE .AND CASES FOR PART TWO Exercise: Weighted Application Blank

advertisement

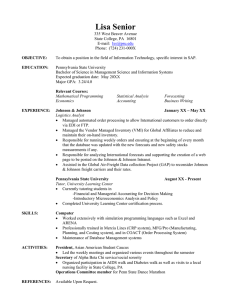

EXERCISE .AND CASES FOR PART TWO Exercise: Weighted Application Blank The Rolla Store is a large establishment with a current roster of 20 sales personnel. The turnover has been high and management is interested in reducing it through the hiring process. Ten of the current 20 people have been with the store a relatively long time. Their characteristics are given in the table on page 188. Analyze the above information for "stayers" and "leavers," and develop a scoring system that would keep more of the stayers and reject more of the leavers. Calculate the percentage efficiency of your cutoff score. Case: The Dekker Company (job design) The Dekker Company was a large manufacturer of electrical equipment for control devices and for the radio and television industry. In its Louisville, Kentucky, branch plant the company manufactured a complicated switching mechanism used in specialized electrical apparatus. The switching mechanism was produced in Department C, one of the three major operating departments shown in Figure 1. The works manager was responsible to the company-wide vice president of production for plant operations. Reporting to the works manager were six division managers. Each division was separated into departments, such as the switch department (Department C). Each department was further divided into sections and groups .. " The production employees of the company, including those in Switch Department C, were represented by a local of an international labor union. The labor contract specified a typical grievance procedure of five steps beginning with "informal, oral discussion Weighted Application Blank Name Age When Hired Education Experience Previous Job Total Previous Experience Experience Rolla Store Marital Status Number Children Ht. Wt. Time at Present Address Merit-rating (high-1; low-7) Phyllis 23 h.s. 3yrs. 4yrs. 7 yrs. Single 0 5'5" 115 5yrs. 4 Ann June Beverly Ed Ruth 26 21 23 22 24 4 2 4 3 3 8 2 4 3 4 6 6 6 7 5 Married Married Married Married Married 1 0 1 1 0 5'6" 5'2" 5'7" 5'11" 5'4" 120 105 130 175 110 6 5 6 6 7 3 3 4 6 6 Julie Wayne 23 24 1 3 4 3 7 8 Married Married 2 2 5'5" 5'11" 111 170 7 2 3 6 George 25 4 8 5 Married 1 6' 180 8 6 Jane 22 h.s. h.s. h.s. h.s. 2yrs. call. g.s. 2yrs. call. 2yrs. h.s. h.s. 3 3 6 Married 0 5'8" 135 5 4 Single Single Single Married 0 0 0 1 5'10" 5'9" 5'9" 6' 175 135 165 190 1 2 7 7 5 4 6 1/2 Single Single Single Single Married 0 0 0 0 1 5'11" 5'11" 5'8" 5'4" 5'10" 185 175 180 105 170 2 1 1 2 1 6 5 3 5 3 112 Single 0 5'8" 145 1 2 Going through the records, the following 10 employees had either resigned or had been fired: Charles Mary Joe Peter Bill John Bob 25 19 21 24 Sam 23 23 24 26 24 Dick 25 Lu.mr call. h.s. g.s. 2yrs. call. g.S. h.s. h.s. call. 2yrs. call. call. 2 1 1 2 8 1 6 2 2 1 1 4 1 1 4 7 6 3 2 2 1 1 2 1 4 112 1 1/2 1/2 1. 189 Psychological Tests and Identification of Management Talent FIGURE 1 The Dekker Company (Louisville branch) partial organization chart. between the Section Chief and the Authorized Representative, except that grievances regarding a job wage rate could not be initiated until "60 days subsequent to the setting of such rate," in order to give the new rate a fair trial. About 75 piece parts were required for each switch made in the switch department. The switches were assembled on an "assembly conveyor" by about 15 employees. They were then placed on an overhead conveyor that carried the assembled switches to an "adjusting conveyor" in an adjoining area. Here, 13 men performed about 50 electrical and mechanical adjustments on each switch. The adjusted switches were sample-inspected by members of the inspection division, and then loaded on a transpol't rack for a delivery to another building. The standard output from this adjusting conveyor was 60 switches per hour. The adjusting line was set up on this basis. The 50 switch adjustments were broken down by the engineering department so that each of the 13 workers performed only a few adjustments on each switch as it went past on the conveyor belt. Through the use of time-study data, the engineer on the job balanced the line so that each position required an equal amount of time. Certain adjustments were more difficult to make than others. In recognition of this, the workers who made the difficult adjustments were assigned a higher labor grade. The four labor grades on the adjusting line ranged from Grade 10 (the second lowest grade in the factory) to Grade 14. The rate difference between each grade was 5 cents, and each grade had a within-grade range of 8 cents. All adjusters were paid a day rate. Engineering Department C serviced the switch shop. The engineers determined the method of manufacture, established time standards for each job, and authorized the purchase of all new machines and equipment. They prepared manufacturing layouts which the operating department was responsible for following. For example, a written layout by the engineering department covered the switch-adjusting operations for the l3-person assembly line. The sequence of adjustments and the duties of each position on the conveyor were described in this layout. The department head in the switch shop, Eugene Moore, had been with the company for 24 years. He had been a department head for 12 years. His subordinates considered him to be a "company man," that is, he had a firm management viewpoint and lacked close touch with employees in his department. The section head in the switch-adjusting section, Jack Richter, was a young man about 30 years of age. He had been recently transferred to his present line supervision job, after working several years at a desk job in the production-control department. He was energetic and aggressive. He wanted to "get ahead." The adjusters did not like him, although he got along well with most other persons in the switch department. The group chief on the adjusting conveyor, Al Olsen, had been with the company less than 2 years. He was young, had a pleasant personality, and was well liked by the adjusters. He was conscientious but not aggressive. He found it difficult to discipline his charges, many of whom were young men in their first job. Ten weeks ago the daily production schedule was increased from 480 switches to 720 switches by management in the company home office. Thus the standard hourly production, or "SHP" as the workers called it, had to be increased from 60 to 90 switches, if the plant was to remain on a one-shift basis. It was not feasible to install another conveyor, and it was company policy to manufacture on a one-shift basis insofar as possible. The existing conveyor, with minor modification, was capable of taking care of as many as 24 people. Upon notification of the new schedule, the engineer revised the adjusting operations, adding some preliminary operations and changing the sequence of others, in such a manner that 18 workers could adjust 90 switches per hour. Time standards, previously established for each element of work, were used as the basis for rebalancing the "line" to turn out the increased schedule. Because each adjuster had less time to spend on each switch, it was necessary in some cases to divide a complicated or lengthy adjustment into two parts, a preliminary adjustment and a final adjustment. One person would make the preliminary adjustment, and a second worker on the line would make the final adjustment. The new method used the same number of higher labor grades that the old one used. From the engineering standpoint, the new method of adjusting switches was just as good as the old method. The new method was covered by an engineering layout and given to switch-shop supervision through regular channels (that is, lines of authority). The project engineer realized that some "bugs" might develop in a change of this magnitude, so he notified Al Olsen informally that when the new method was introduced on the conveyor, the engineers would watch operations carefully for possible trouble. When Richter and Olsen received the new engineering layout and instructions, they protested that they did not want to use the new method because: 1. They believed they could not meet the higher SHP, even though the time standards indicated that they could. 2. They did not have the 5 additional trained switch adjusters required by the new layout. They wanted to continue adjusting according to the old method on the day shift, but to hire 5 new employees to work on this day shift, thus relieving experienced people to work on a second shift. The second-shift line would run on a kind of partial conveyor basis. Operating in this manner, and by working an overtime day on Saturdays, they believed that the increased schedule could be met. At Moore's insistence, backed by the project engineer, the 18-person line was placed in operation without giving much consideration to the alternate proposal. Some minor "bugs" in the adjusting procedure were discovered but readily eliminated, and it was proved to the satisfaction of the engineering department that the new method would work. The SHP of 90 was not met at first, but this was expected by the engineers, since the employees needed time to gain experience. From the very first day, however, the adjusters did not like the new arrangement. They felt that the new sequence of operations would not work. They did not like the idea of subdividing some of the lengthy adjustments into two parts. They thought that the new SHP was too high. In general, they griped to Olsen, to the engineer, and to anybody who would listen. One habit they developed at this time was to place metal tote boxes on the floor under the adjusting table and drum and pound on them with their feet while they worked. Often they did this in unison several times a day, making a terrific noise which disturbed nearby departments. The employees were not disciplined because Richter felt he needed their goodwill and cooperation in order to meet the increased schedule. The schedule had to be met within a few weeks; otherwise the backlog of adjusted switches would be exhausted, which would idle several hundred employees in later production stages. This unsettled situation continued for 4 weeks. Output gradually increased, but it leveled at 5 to 10 switches above the old SHP of 60 switches. In addition, the quality declined precipitously. The inspector rejected many of the completed lots. The stock of adjusted switches became so short that Richter took the following emergency actions: 2. He established a partial second shift using 4 new employees and 5 regular adjusters. The regular adjusters were replaced on the first shift by 5 new employees. 3. He placed both shifts on a 10-hour day. This required that the two shifts overlap from 1:30 to 5:30 P.M. Since there was adequate space, the second shift during this overlap sat at side benches and reworked switches that had been rejected by the inspectors. 4. He scheduled one Saturday shift using as many persons from both shifts as wished to work. While checking the night shift, about 6 weeks after the chan~, Richter privately approached one of the adjusters who was quite friendly with him, and asked him to "check up" on the activities of the other adjusters. Richter wanted him to report any adjuster who was not working diligently. The adjuster told several of the other adjusters, and the men began to "simmer." At about 10 P.M. the adjusters refused to work any longer. One of the men called Al Olsen, who was at home, and told him about the trouble. Olsen called Moore and they both came to the plant. The adjusters were told by Moore to go back to work, and they did. So much hard feeling developed from this incident that management decided to transfer Richter to another plant in another city during the following week to give him a fresh start. An experienced supervisor named Gene Smith was brought from another department to fill Richter's job. Aside from this incident, whenever the supervisors did advise and lecture the employees about maintaining high quality, the employees answered by pointing a finger of blame at defective switch parts. They claimed that adjustments were too difficult to make because of poor piece parts which made up the switch. Some adjustments concerned a clearance between moving parts. For example, one part had to clear another part by at least 0.005 and not more than 0.01 inch. The first part also had to be parallel to the second part. Therefore, if during piece-part manufacture the parts were not deburred properly, were not milled properly, or were not polished smoothly, the adjustments were very difficult to make. Another adjusting trouble resulted because one adjustment might affect adversely a prior adjustment. For example, the thirteenth worker might make an adjustment which would "throw out" the adjustment that the ninth one made. In a case of this kind, the thirteenth worker was supposed to recheck the adjustment made by the ninth one to make sure that it was not disturbed. All of the adjustments were involved to this extent. It was, therefore, difficult for inspectors to pinpoint causes of poor quality without a special investigation. There was a special investigating staff for that purpose. Ten weeks after the changeover, production was still below 90 switches hourly, quality was bad, and the stock of finished switches was almost exhausted. The operating division manager called a conference to try to determine a solution to the adjustment problem. He invited the project engineer and his manager, the project inspector and his manager, the switchdepartment head (Moore), the three switch-section heads, and Olsen. Questions: 1. What is the number of units per employee-hour being produced when the case opens? What is this at the end? How do you account for the difference? 2. What approach to job design is being used by Dekker? What are the alternatives? What impact would these alternatives have on quantity and quality? Case: Tw'o Masters (any subject) The Adamson Aircraft Company has in the last decade expanded its product line to include the design, development, and production of missiles for the United States government. For this purpose a missile division was established, and over."5,OOO personnel were gathered to man this portion of the firm. The traditional type of organization in aircraft manufacturing calls for functional specialization like that found in the automobile industry. Aircraft are made up of such items as engines, radios, wheels, and armament. The manufacture of component parts was standardized and the aircraft put together on an assembly line. It was quickly recognized that such a simplified approach would not meet future requirements, as the demand for greater capability and effectiveness increased and forced the designers to insist upon optimum performance in every part or component. Several components, each with an operational reliability of 99 percent, may have a combined reliability of only 51 percent. Even with the most judicious selection and usage of standard parts, a system could end up with a reliability approaching zero. To overcome this reliability drop, it became necessary to design the entire system as a single entity. Many of the parts that were formerly available off the shelf must now be tailored to meet the exacting demands of the total system. Thus, the "weapons system" concept was developed, which necessitated a change in organization and management. For each weapons system project, a chief project engineer is appointed. He assembles the necessary design personnel for every phase of the project. In effect, he organizes and creates a small, temporary company for the purpose of executing a single weapons system. On his staff are representatives of such functional areas as propulsion, secondary power, structures, flight test, and "human factors." The human factors specialist, for example, normally reports to a human factors supervisor. In the human factors department are people with training in psychology, anthropology, physiology, and the like. They do research on human behavior and hope to provide the design engineers with the basic human parameters applicable to a specific problem. James Johnson, an industrial psychologist, has been working with the missile division of Adamson for 6 months as a human factors specialist. His supervisor, George Slauson, also has a Ph.D. in psychology and has been with the firm for 2 years. Johnson is in a line relationship with Slauson, who conducts his annual review for pay purposes, and prepares an efficiency report on his work. Slauson is responsible for assembling and supervising a group of human factors experts to provide Adamson with the latest and most advanced information in the field of human behavior and its effect on product design. Johnson has been assigned to a weapons system project, which is under the direction of Bernard Coolsen, a chief project engineer. In a committee meeting of project members, Coolsen stated, "I am thinking about a space vehicle of minimum weight capable of 14 days' sustained activity, maneuverability, and rendezvous with other vehicles for maintenance and external exploration. How many people, how big a vehicle, and what instruments, supplies, and equipment will we need?" Johnson immediately set to work on his phase of the project. The data for the answer to this request were compiled and organized, and a rough draft of the human factors design criteria was prepared in triplicate. Johnson took the original to his supervisor, Slauson, for review, retaining the other two copies. Using one of the copies, he began to re-edit and rewrite, working toward a smooth copy for presentation to Coolsen. A week later Johnson was called in by Slauson who said, "We can't put Ql,lt stuff like this. First, it's too specific, and secondly, it's poorly organized." Slauson had rewritten the material extensively and had submitted a draft of it to his immediate superior, the design evaluation chief. In the meantime Coolsen had been calling Johnson for the material, insisting that he was holding up the entire project. Finally, taking a chance, Johnson took his original copy to Coolsen, and they sat down together and discussed the whole problem. An illustrator was called in, and in 2 days the whole vehicle was sketched up ready for design and specification write-up. The illustrator went to his board and began converting the sketches to drawings. Coolsen started to arrange for the writing of component and structural specifitations, and Johnson went back to his desk to revise his human engineering specifications in the light of points brought out during the 2-day team conference. Three days later the design evaluation chief called Johnson into his office and said, "Has your supervisor seen this specification of yours'?" Johnson replied that he had and that this was Slauson's revision of the original. The chief then asked for the original, and Johnson brought in the third original copy. Two days later the chief's secretary delivered to Johnson's desk a draft of his original specification as modified by Slauson as modified by the design evaluation chief. Johnson edited this for technical accuracy and prepared a ditto master. Slauson and the design evaluation chief read the master, initialed it, and asked for 30 copies to be run off. One copy was kept by Johnson, one by Slauson, one by the chief, five put into company routing, and the balance placed in file. Those in company routing went to the head of technical staff, head of advanced systems, and finally to the project engineer, Coolsen. Coolsen filed one copy in the project file and gave the other to Johnson. The latter dropped it in the nearest wastebasket, inasmuch as several days previously, Coolsen had combined his, the illustrator's, and Johnson's material and submitted it to publications. Publications had run off six copies, one each for Coolsen, the illustrator, Johnson, the head of advanced systems, the U.S. Patent Office, and one for file. Also, by this time, the vehicle had been accepted by the company management as a disclosure for patent purposes. Johnson breathed a sigh of relief, since he thought that he gotten away with serving two masters. Questions: 1. Why does the organization wish to have two bosses for Johnson? 2. Coolsen and Slauson are both interested in "good quality" work from Johnson. What is each manager's definition of "good quality?" Case: The Worried Attorney (JA and Selection) George Helms paced the floor of his den. It was 2 A.M., and his wife had urged him to stop worrying and go to bed. George felt, however, that he had to make a decision before he could sleep. Which of the two young law graduates should their law firm of Harrison, Holmes, and Helms hire? Since the one chosen would presumably be a partner some day, the decision was doubly important. As he worried about the choice, his thoughts returned to his own graduation day 15 years ago. While growing up near San Francisco, he had always felt that his family, especially his father, had kept him on a particularly tight leash. Sometimes Helms resented the fact that his father was such a prominent judge in the Bay area. Despite doing well in school and sports, he was never sure he had done as well as his father had expected. Upon graduation from law school he had been accepted by the State Department for a foreign assignment in France. Instead of his father's being pleased, he had strongly advised him to turn down the appointment and COme back to San Francisco to enter the firm of Harrison and Holmes. The discussion concerning this had been long and sometimes bitter. In the end, George had returned to San Francisco, and as he reflected now, it had been for the best. He had been quite happY·\\Iith this old San Francisco law firm. Helms's mind next moved to the first of the two applicants who were being considered. Eleven in total had applied or been asked for the opening in the firm. All were recent law school graduates. The field had been narrowed to two, Bruce Hargraves, who had received his law degree from Michigan 4 years ago, and Roger Parnes, who was graduating from Stanford this year. As George pondered his decision, he asked himself why Harrison and Holmes had left so much of this decision on his shoulders. Bruce Hargraves ... surely a top-flight student ... second in his class ... had been one of the editors of the school's law review ... had also done some teaching ... was active in local Democratic politics ... wonder where he got the time for all of this? Helms recalled that Hargraves had taken a job with an oil company in Iran after graduation. He recalled in the interview that he had asked why, and that Hargraves had snapped back that it was for the money. Hargraves then had told him about his childhood and teenage years in Columbus-how he had always had some kind of job since he was 12, and how he had been arrested for street fighting when he was 15. Helms recalled that Hargraves had won an engineering scholarship at MIT but had turned it down. He had gone to Michigan instead. Hargraves told how he had it figured out that he had enough money to get through the football season without taking a job. In the winter, he got a 6-houra-day factory job in Willow Run and also received a small athletic scholarship. Helms recalled asking if he had ever played varsity ball at Michigan. Hargraves had replied that he and the coach had had an argument, and that he quit the squad as a result. Hargraves added that he was able to make more money playing semipro industrial football on Saturdays and Sundays. George recollected that Hargraves's grades in college were surely outstanding; in fact, he had graduated a member of Phi Beta Kappa. Other data concerning Hargraves came to mind. He had turned down a bid from a fraternity because he could not afford it. He had been quite active in campus political clubs. That, he said, had helped him get a summer job in the Governor's office one year. When Hargraves graduated from college, he was almost immediately drafted. He had told Helms that he had become a sergeant and had seen quite a bit of action. When asked about his marital status, Hargraves had artfully dodged the question. He said he had no plans to settle down until he was a tired old man of 40. Helms remembered smiling at the remark but thought it a little brash. George decided that there was something in Hargraves's manner that disturbed him. He remembered the day the two of them had driven to Oakland in Hargraves's Austin-Healey. He had felt the same way that day. He just could not put his finger on what it was, though. Helms's attention now shifted to Roger Parnes. He could not quite get used to the idea of young Roger Parnes becoming a member of his or any other law firm. Though he had not really known Roger before he had made application to the firm, he had seen him around the San Francisco area for years. Roger's father had been a friend of the family, though he could not remember his ever coming to the house. He and Roger had played golf in the same foursome a time or two. George laughed to himself as he recalled that until recently he had thought that golf was Parnes's greatest accomplishment in life. Reading Roger's transcripts had shown George that Roger's brain was more agile than he had realized. Though not brilliant, he had been in the top third of the Stanford Law School class during his first 2 years. This did not stack up to Hargraves's record, but it was certainly acceptable. Actually, Roger had a bit more legal experience than the other man. He had spent the past six summers working as a law clerk. Hargraves's job with the oil company had not been in the legal field, though he was hired for his law training. Thinking back to Hargraves, George reflected he had sort of a take-charge quality that many people probably admired. He was unable to find such a quality in Roger, though he knew that Roger got along well with people. He reasoned, therefore, that people must certainly have looked to Roger for leadership. When Roger was very young, he had considered him to be a "mamma's boy" with his carefully combed hair and almost too well-groomed clothes. Later recollections included him on the golf course, racing his sailboat, and at a dance or two with Charlotte Gilmour. Charlotte's family had been very close friends of George's, so he had gotten to know Roger a little in this way. Roger's only years away from California were two spent in the service. George did not recall where. George lighted another cigarette and paced some more. Why had Fletcher Harrison and Charles Holmes left the decision up to him when they were the senior partners? He very well knew how each stood. Fletcher had said that George should make the decision, and then added that, from the interviews, young Parnes appeared to be very capable. George then thought back to his own father's comments that when Helms, Sr., and Harrison were in law partnership, Fletcher sometimes took days to express an opinion or make a decision. Charles Holmes had made his feelings more obvious. Charles had been given his first job by George's father. He said he thought Hargraves was the sharpest young fellow he had seen in a long time. Helms smoked and paced some more. He sat down and decided that Roger Parnes would make a fine member of the firm. Feeling relieved, he went to bed. On getting up the following morning, he thought a bit more about his decision. Although not completely satisfied, he decided that all had worked out for the best. Questions: 1. What are the specific major differences in characteristics between the two candidates? 2. What type of firm image is implemented by the hiring decision? 3. How do job analysis and role analysis differ in this case?