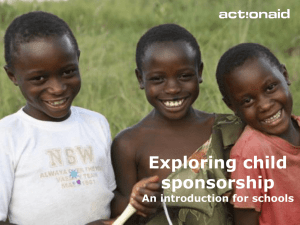

Action Issue 23

advertisement