The local labour market effects of immigration in the UK

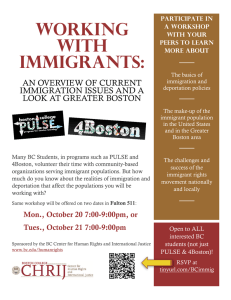

advertisement