KAHBH Standard Operating Procedures And

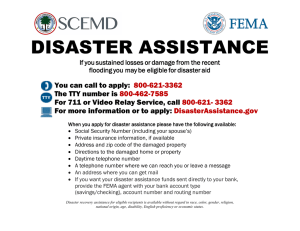

advertisement