International tourists’ decision making: Perspectives from frontline

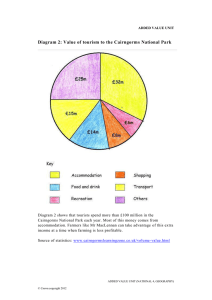

advertisement