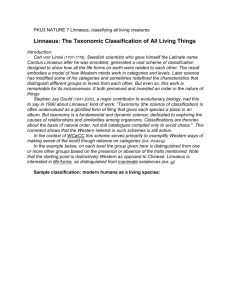

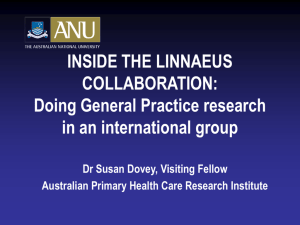

“Little Brother Carl” – the Making of a Linnaean Naturalist... Eighteenth Century Sweden

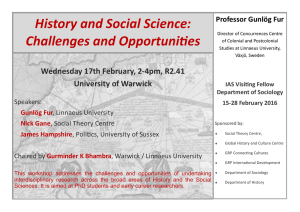

advertisement