Linnaean Naturalists in London - Transnational Environments and the

advertisement

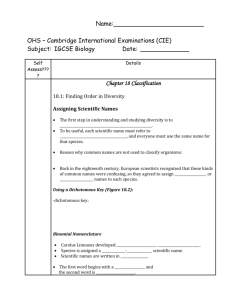

Linnaean Naturalists in London - Transnational Environments and the Formation of Scientific Personæ in Late 18th Century Europe Introduction First of all I would like to say thank you to Marie Christine for inviting me to this symposium. I am really happy to be here. As you all know this symposium is organized in conjunction with the finalization of Marie-Christine’s project on Carl Petter Thunberg. I am in a very different position to Marie Christine, I just started a new project, ”Westward science – social mobility and the mobility of science 1760 to 1810”. It is funded by Vetenskapsrådet, and will run until 2014. I will work on it part time, while also working on a project on East Indian trade in Warwick together with Maxine Berg who will talk here tomorrow. Today I am going to present some of the central thoughts and ideas behind my new project. Needless to say I am very open to comments and suggestions on how I can refine my approach. What I am going to say is also only based only a partial reading of available source material. I thought I start with Thunberg and his long journey, because he plays a small but not insignificant part in my new project. As you all probably know before returning back to Sweden in March 1779 Thunberg made a detour to London. It is with this detour, and the reaction among Thunberg’s contacts in Sweden to the news of it, that I want to start my discussion. One who was particularly worried was Abraham Bäck. Most of you are probably familiar with Bäck, he was president over Collegium Medicum, the Swedish Royal Society of Physicians, and Linnaeus’ best friend. In fact Linnaeus and Bäck had long acted as “twin patron” within the realm of Swedish medicine and natural history. Many of the students of Linnaeus educated in Uppsala ended up filling positions Bäck was in charge off, and Bäck paid special attention to those interested in natural history, he frequently offered them help and advice, not at least Linnaeus’ apostles, of whom Thunberg was maybe the most successful. The prospect of a visit to London Bäck writes to Thunberg in Amsterdam, in October 1778, something along the line of: “By God promise me not to be convinced by the flattery and grand promises of the English” (Thanks Marie Christine for the reference). He seemed worried Thunberg would not return, that he would do what Daniel Solander had done less than twenty years, i.e. abscond to the British, dump Linnaeus and Bäck as patrons and become a client of Joseph Banks, Solander’s co-explorer on Captain Cooks first expedition and later president over the Royal Society. I will return to him soon. In worrying about Thunberg’s future career, Bäck was not alone, there were many concerned, foremost maybe the X in X Bergius and Lars Montin, provincial physician in Halmstad on the west coast of Sweden, and owner of the supposedly third biggest herbarium in Sweden, next after Abraham Bäck and Linnaeus himself. Both Bergius and Montin were former students of Linnaeus. And here I have read quite a lot of the letters from Montin to Bäck which often touches on the topic of Thunberg. They give a deeper understanding of Bäck’s fear for Thunberg staying in London, and some of this is of course quite well known. Thunberg was fed up with complaints from Linnaeus that he was not the sole receiver of material from Thunberg, that Bergius, who of course Linnaeus was not getting on with very well, had managed to move in, to become recipient of material from South Asia and beyond. That Montin himself, who had invested in Thunberg’s journeys, was not too happy about some of the descions taken by Thunberg about how to proceed in Asia does is also clear from Montin’s letter to Bäck. However Montin was also happy to collaborate with Thunberg in passing on threats, printed in X by Y, that Thunberg might not come back: In other words, Thunberg had threatened to not return before, suggesting that he would settle down in India, which if not part of the British isles, belonged to the British East India Company and the British empire. In the light of this Bäck’s fear that Thunberg would fall for the flattery and grand promises of the English might not have been so far fetched. The concern over Thunberg, that he and his collection, would not come home, is also reflected in how his supporters at home discussed his future employment. This is one re-occurring theme in Lars Montin’s letter to Bäck. And, here again another name another reference to London as a potential for Swedish naturalists to work occurred, in the form of Jonas Dryander. Dryander was nonetheless than Montin’s nephew, on his sister’s side. Between X and Y there are several mentioning of Dryander in Montin’s letter to Bäck. A not to unlikely reason is that Montin was trying to engage in Bäck in finding an employment for Dryander, to take him on as a client. In letter after letter Montin discusses the poor prospects Dryander had. And then of course Dryander moved to London, and found employment with Banks, he is the second of Bank’s Swedish secretaries. Dryander and Thunberg were in fact two of a large group of Swedish naturalists that headed west, to London and beyond, from the middle of the 18th century and onwards, together they form the starting point for my new project on west ward science and scientific and social mobility. Here is a list of Swedish naturalists that came to London and England between 1760 and 1810. The dates correspond to arrival of Solander to London and the death of Dryander in 1810, who ended up working for Banks for the rest of his life. The list is not conclusive but include some of the people I am planning to research more thoroughly. Understanding migrating naturalists Now how are we to understand this migration of naturalists west wards? Well there are several ways, pending on where we start. General historical Within a Swedish context it seems reasonable to refer to the loss of natural history of its popular appeal in late 18th century Sweden. This development has typically been understood in the light of the decline of the Hat Party, as well as new intellectual and cultural movement, physiocratic ideas replaced mercantilism and literature, art and history replaced natural history among the interests cultivated by the elite. Within a British context, there is of course Joseph Banks and his support for natural history, which gained strength in the light of the expanding empire and the importance associated with natural history in promoting production and trade. There was also the particular admiration for Linnaeus in Britain, where in contrast to in France was much celebrated. There seems to be both push and pull effects explaining what one might call a brain-drain, from Sweden to Britain. A global and social history of science There are however explanations and ways of thinking about this, which does more than emphasis the historically specifics of Sweden and Britain. Which instead tries to situate this migration in the historical and scientific context of the time. One way I am planning to frame this processes is to think about it as one linking two specific formation in which science was done, firstly the early modern Republic of Letters and secondly, the national and imperial science that we typically associated with the 19th century and onwards. A common way to distinguish between these two structures is by focusing on the consumers and producers of science. The early modern period has typically highlighted the Savants. Or amateur, if we use the contemporary definition of this term, meaning a lover of something. It is only in the 19th century that amateur become the opposite to professional, something which reflects the specialization and professionalization that science underwent, both in academic and commercial contexts. Another way to contrast the two ways to organize science is to compare the role of collections and expertise, Alix Coooper has described early modern natural history as a “lapptäcke” of regional experts with small collections. The beginning of modern science on the other hand was marked by the increasing importance of national and imperial centers Another, and closely related way to analyse this process is to think about it as part of a process of how science and knowledge became globally accepted and applied. Linnaeus taxonomy and particularly the Linnaean nomenclature, the binary name system, launched internationally with Species Plantarum in 1753, was instrumental in promoting a global natural history. That Linnaeus students, particularly those who travelled far were part of this process, is something that many historians touched on, although more exactly how is something which I would like to focus on in the project, I will return to this later on in the paper. However, of course no one forced Linnaeus’ students to travel to London and other places. And here I am hoping to contribute with some new questions and answers. I suggest we need to look closer at the motives of the travelers, e.g. what can their move to London say about how these agents thought about their own career prospects and the roles they imagined they would play in natural history. It would be an anachronistic assumption to assume that they saw their own role as part of the grand historical process which helped to bring down the Republic of Letters, and promote national and imperial science. By focusing on their own motives I hope to explore the link between social mobility with the mobility of science. Here I am hoping to be able to contribute to recent scholarship that focus on spatial aspects of science production and consumption, research that typically discuss both how local aspects form how science is done but also how knowledge travel, looking at circulation of objects and communication between agents. Scientific Personae between two different knowledge structures Daston Otto: explanation of the notion of scientific personae Scientific personae Linnaeus notions of botanists Taxon article Science pedagogy In other work I have published I have tried to define what constituted a Linnaean natural historian looking history of education, Linnaean education, how it formed their scientific personae. Trained to work on the field, to see and observe, embodied knowledge Closeness between education and exploration on the field Trained in principles for describing species, Trained in the art of organizing and displaying collections Meritocratic dimension to this educat Education of course only one phase in the forming of scientific personae, the London environment offered other opportunities: My argument is that the journeys between Uppsala – London, link or axis give us an idea about a wide range of scientific personae that the existed and or was generated: Metropolitan naturalists Bank’s breakfast meetings, Royal Society, on Linnaean Society Afzelius – catching up on the reading, notes Social dimension, Not having a science household Dryander, Solander, Afzelius marriage, Traveller/observer The case of Solander and Afzelius also demonstrate the problems associated with launching a career based on a journey Mungo Park… Thunberg, more successful, Administrative naturalist Metroplitan too, but needs to be understood against the backdrop of collections, Solander, Dryander, Torner… Commissioner and representative in natural history Intellectual commissioner Representing societies and individuals, bridging national language groups Transmitting material and ideas, This role enabled individuals to move back and forth How can these roles help us understand the globalization of natural history knowledge? Not everyone could afford Metroplitan Science, it was a hard word to hard word to penetrate. Linnaean knowledge was central at the Centre, but mainly exercised by people who were in a subordinated role… The number of Swedish naturalists making the journey to London suggest that we can maybe thinking about the existence of an axis connecting Uppsala maybe particularly, and London. I have chosen the word axis because it does suggest an alliance, and this alliance based on Linnaeus and his legacy. It was concerned with the application of Linnaeus principles when describing, defining and naming species. Although an alliance it was a relationship that was colored by a somewhat asymmetrical distribution of power and influence, it was London which pulled Swedish naturalists to England, not the other way around. However, it is also important to acknowledge that the move or journey to Britain was not a oneway movement. There are many examples of naturalists returning, after longer or shorter stays. In that respect the movement of Swedish naturlists do not compare to e.g. the diaspora of Hugenots that X has written about, or the Jewish intellectual refugees in modern times. One question which I would like to look at further is the extent to which historical agents I am investigating thought about this one can ask is to which extent this this axis or alliance was significant The relationship between London and Uppsala, was in that respect different form Material connection - Linnaeus’ collection Network, personal contacts, not only scientific but also religious… Swedenborg connection is an important one Socially: weakness, inbetween patrons, information about opportunities: constantly keeping an eye out for different prospects and opportunities, insecurity to make the step: did that make them behave in a specifically innovating way? Trying to keep as many opportunities open as possible? Going back and forth, some, others, staying put, others (Afzelius) can’t make up his mind. Cf: intellectual diaspora, not forced to stay away from home, s, Hugenots… but here no return back….), German jewish diaspora…. Indian intellectual diaspora….