Assessing the Effectiveness of the Kosrae Island Resource

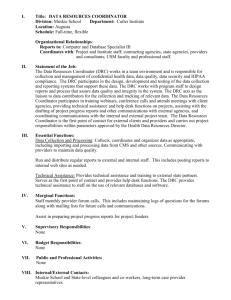

advertisement