Document 13180158

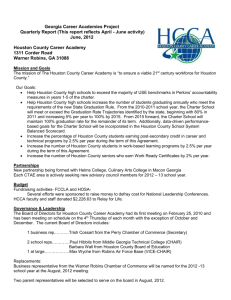

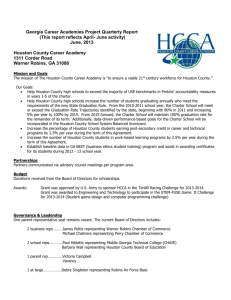

advertisement