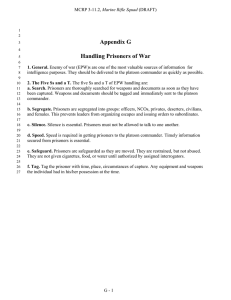

‘A little Britain-beyond-the-seas’: The British prisoners of war at Verdun... French Empire (1803-1814) In 1803, Napoleon’s unforeseen order to arrest...

advertisement

‘A little Britain-beyond-the-seas’: The British prisoners of war at Verdun under the First French Empire (1803-1814) In 1803, Napoleon’s unforeseen order to arrest every British civilian present on the French soil led to a remarkable and yet unknown detention. Almost one thousand wealthy British, mostly aristocratic tourists were sent to Verdun, a remote town in North-East France, as prisoners of war. Yet, far from the orthodox image of the military hostage, these British captives enjoyed a remarkable amount of freedom. Considered as prisoners on parole by the French authorities, they were permitted to live among the inhabitants, which enabled them to recreate a British way of life. Horse races, whist clubs, Shakespearean amateur theatre and other festivities were organised by this fashionable society of detainees, transforming the sleepy town into an exotic British enclave, where, as a contemporary argued, ‘upon the whole, the prisoners lived happily together’ until their release in 1814. Despite its unique colourfulness, this detention has long remained neglected by historians. Mentioned in dated military or maritime studies (Lewis, 1962), or else by certain early twentieth-century writers (Monvel, 1911; Fraser, 1914; Elton, 1945), this peculiar and truly fascinating captivity deserves greater attention. By providing a first synthesis on this unprecedented detention at Verdun, my doctoral research, facilitated by my fluency in both French and English, will hence bridge a gap in our knowledge of the Napoleonic wars and the broader issue of the relations between France and Britain in the aftermath of the French Revolution. My project is to illuminate the process by which the presence of civilians alters the experience of military captivity. First focusing on the emergence of an organised community establishing schools and Anglican churches and raising funds through a financial network between Verdun and the Lloyds Patriotic Fund in London, I will analyse the experience of forced exile in an alien country as an opportunity to discover the ‘Other’. The analysis of the cultural, social and economic relations between the French inhabitants and their ‘guests of honour’ will lead me to consider the depot as an interface between two cultures, two nations supposedly enemies. The abundant narratives of captivity written by the British provide an insight into the prisoners’ everyday life, but they also raise key issues on the construction of memory and oblivion, and ‘methodological individualism’ (Popper, 1956). Inspired by Benedict Anderson’s thesis, my intention is to reflect on the broader epistemological question of the use of these literary documents as a source for the historian, and study them as an essential component of an ‘imagined community’ that emerged among former prisoners. In this project, Professor Carolyn Steedman’s expertise in the literature of the self will provide invaluable supervision. Having begun the study of this subject for my MA in France, I am already familiar with the material available in the French national and local archives on the question. I am to present my first discoveries at the forthcoming ‘Making War, Making Peace’ CTHS Conference in Perpignan in May 2011. Furthermore, I have already consulted a great number of letters and memoirs during my current Erasmus year at Warwick. The rest of my sources being located in Birmingham City Archives, Warwickshire County Record Office and the National Archives in London, Warwick will be the ideal place to undertake a PhD on this transnational subject.