COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS IN THE DEVELO T III

advertisement

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS IN THE DEVELO PfiE NT

OF WATEq P.ESOURCES

CECIL CRAWFORD KUHNE, III

Cost-Benefit Analysis in the Development

Of Water Resources

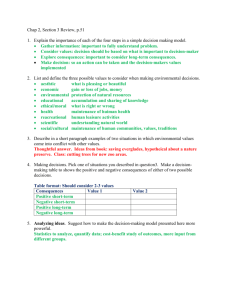

I. Cost-Benefit Analysis: An Overview

A. General Economic Principles

Price theory deals with the flow of goods and services

from resource owners to businesses and eventually to the

ultimate consumer, with the consequent effect of pricing on

the factors of that flow. l

Price theory also seeks to

demonstrate how resource prices allocate resources among

different users and geographical areas.

Only if pure competition

prevails in both product markets and resource markets will

resources automatically be allocated to maximize net national

2

product.

From an individual firm's standpoint, it is most

advantageous to use resources at their least-cost combination

and to use only the absolute amounts necessary in order to

pro.? uce at a level which maximizes profits. 3

Price theory, then, assures an efficient allocation of

resources in private markets, but c~rtain goods which society

as a whole desires will not be produced by the private sector.

The government seeks to provide for t:E!rtain beneficial goods

or services known as "merit goods."

The political process

provides for such merit goods as compulsary education,

subsidized housing, and compulsary health service.

These

meri t goods are· furnished by the government ·, regardless of

economic efficiency.

But collective goods, such as flood

control and national defense, are not furnished by private

firms because of the prohibitive costs.

Collective goods are

provided by the government due to the inability of the

marketplace to produce them, and it is thus necessary that

a formula for economic efficiency be developed in order to

get the greatest possible return on governmental investments. 4

Cost-benefit analysis has its beginnings in welfare

economics, which seeks to improve the well-being of consumers

and producers as persons by means of policy recommendations,S

and as a part of welfare economics,' cost-benefit analysis

is the application of pure allocation theory.6 Welfare

economi.cs had its beginnings in what is commonly known as

the Pareto theory.

The Pareto theory concerns itself with

an economic rearrangement in which the economic gains can

be so distributed as to make everyone in the community

' better

off ~

This, however, is an actual Pareto improvement.

A potential Pareto improvement deals with economic change

which leaves some persons better off, while leaving others

worse off • . If those who gain are willing to compensate the

losers, then there is a potential Pareto improvement.'

It

must be ' noted that although there is a gain in the analysis,

this is a quantitative gain, with some persons still suffering

8

10sses.

And, it may happen that those who lose will not

be compensated. 9 Th'is theory ( as a result, has been criticized

for causing a change in the distribution cif' income since

those individuals with lower incomes may be affected more

by · economic changes than those in the higher income brackets.

Cost-benefit analysis, too, seeks only to aggregate the

benefits of. a project and balance them against aggregate

costs, and if benefits exceed 'c osts, then the plan is eco• •

nomically justified, despite certain" aClverse effects.

B. Assumptions and Procedures

Cost-benefit analysis, like price theory, assumes perfect _

competition and the abse~ce of external diseconomies. lO Any

changes in aggregate inc~me, income distribution, and market

form have a resultant effect on both prices and a cost-benefit

ll

analysis.

Cost-benefit analysis also assumes that maximization

of national income is the I primary, if not the only, .g oal of

water resource allocation. 12

The purpose 'of a cost-benefit analysis is to require an

effective evaluation of the values of a proposed government ,

project, which will in turn lead . to an improved expe_ndi ture

of public funds. 13 It seems however that the purpose has

broadened considerably to encompass other factors. 14 The

method also serves two other basic functions. First, if the

cost-benefit ratio is to be maximized, such factors as the

size of the project 'may be altered in order to provide the

"greatest benefits. Thus, the analyst can ascertain how much

capaci ty a ' dam s'hould contain or how much navigation or

recreational facilities should be expanded. Second, cost-benefit

analysis provides a meansJ for comparing alternatives if the

project has a specific purpose. For example, if a project

is to be constructed to provide electric power, then cost-benefit

analysis allows a determination of whether a hydroelectric

I

dam, a plant using coal, or an atomic plant would be the most

economically efficient. 1S Not all economists agree, however,

that' the cost-benefit ratio can be used to compare different

projects. One commentator points out that using 'the cost-benefit

ratio to compare one project with another is fallacious and

would be analagous, in the commercial world, of using a ratio

.

t

t' d eC~S10n.

•.

16

. t s t 0 gross ' expenses .

o f gross rece~p

~n an ~nves men

A cost-benefit: ratio may cause a misalloca'tion of resources

if projects are not analyzed in a comparative manner. For

example, suppose that two mutually exclusive projects are

' compared, one having a benefit of $S and a cost of $1 (ratio

is 5) and the other having a benefit of $1,200 and a cost of

$1,000 (ratio is 1.2). The first project has a greater ratio,

l

,

17

but it would be undesirable to lose a ~200 gain for a $4 gain.

While cost-benefit analysis has largely replaced price

theory in government investments, it has ,been proposed that

cost-benefit analysis could be expanded beyond public investments

and could be used, for example, in ,private litigation over

riparian water rights. 18

The actual procedure of cost-benefit analysis is

relatively simple. The first step requires an estimation of

installation costs and annual operating costs over the life

of the project. Then the value ' of the project's output must

be estimated by ascertaining the nuinber of units to be

produced and their value. Finally, secondary, or indirect

costs and benefits are computed.

All of the costs and benefits

are then discounted with the appropriate rate in order to

arrive at the present value. 19

The costs are either subtracted

from the benefits, or the results are expressed in a ratio

(benefits as numerator, costs as denomihator), in which a

value greater than unity indicates an economically justifiable

.

20

proJect.

The concepts of what constitutes a benefit and what

constitutes a cost are indespensible to the analysis. The

terms are usually divided into primary (direct) and secondary

(indirect) benefits and costs, and then there is a further

s'ubdivision wi thin each of those two major divisions, with

these subdivisions labeled as tangible and intangible benefits

and costs.

confused.

The concepts are distinct, although frequently

Primary (direct) .costs include the initial expenditures

required to construct and maintain a project.

These costs

also include the value of any adverse effects, whether they

are compensated or not.

The primary benefits are the value

of those goods and services which result -from the expenditure

21

·

o f . t h e d 1reCt

costs.

Secondary (in~irect) costs are costs of further processing

or any other costs "stemming from or induced by" the project.

These costs include the value 'of goods and services necessary .

to make goods available for use or s 'a le.

Secondary benefits

are the benefits to the nation as a result of activities

"stemming frcm or induced by" the projece. 22 The words

"stemming from or induced by" are significant; the former

include processing such as transporting power, and the latter,

23

any change in technology or shifts in supply and demand.

The primary and secondary dichotomies i.nclude both

tangible and intangible benefits and costs.

Tangible benefits

would include the value of cotton produced as a result of

new irrigation sources/ tangible costs are. the costs of the

darn.

The rehabilitation of a drinking ground for waterfowl

might be an intangible benefit arising from a project, while

-5-

the same proje.ct would create an intangible cost by the

construction of a dam which would interfere with anadromous

fisheries. 24

C. "Willingness to Pay" and Alternative Costs

The benefits of goods and services produced by the market

system are easily ascertained, but benefits without market

values a.re determined by the concept of "willingness to pay."

In the Pareto theory, the willingness to pay is that amount

which the winners of economic change must pay to the losers

if the change is to take place. 25 The willingness to pay may

be estimated by the analyst, or it may be obtained from those

individuals who are to be affected by the change in environmental

quality, either through a referendum approach or opinion polls.26

Thus, the welfare economist is able to provide for a means of

det.ermining value in the absence of market mechanisms.

Economists

have also expanded upon the definition of

.,

costs.

Outlay costs are those costs required for construction

- and maintenance of a project, such as wages, equipment, taxes,

and so forth.

The alternative costs, or opportunity costs,

are normally· defined as "the value of the benefit foregone

by choosing one alternative rather than another."

This is

an important concept since the real cost of any activity is

measured by its alternative costs, not its outlay costs. 27

Due to the scarcity of resources, those resources used by a

firm in the manufacture of a product ~ause the total amount

of available resources to diminish, if only slightly.

If

units of a certain type of specialized labor can only be used

to asserr~le washing machines or refrigerators, then the costs

of ~he resources to the firm are the values in their alternative

uses.

The firm which decides to manufacture washing machines-

must pay the value of refrigerators that the labor could have

produced.

I.£ the manufacturer of washing machines refuses to

pay the alternative costs, then the labor will remain in

refrigeration producticn. 28

Alternative cos.t s are measured by means of input-output

tables, which show the, flow of goods and services from industrial

sector to the ultimate purchaser. 29 The input-output analysis

can also be used to assess the contributions of various

sectors of .the economy to' the disturbances in t,he ecosystems. 30

,Alternativ.e costs are used not' only to ascertain total

costs but also benefits. In cost-benefit analysis the benefits

are equal to ,the alternative cost, or the "cost of providing

comparable output by ' its cheapes,t alternatl.vc mer-me." These

alte1'nativc costs are widely used in power. ftlunicipal waste

supply, and naviga,tion. 311

The use of cost-benefit analysis in the allocation of

resources is ",lsc· infhlE,nccd by the concept of utility.

Apparent,ly, the su,bjectiye utility of society which is derived

frem consuming 9,o ods and seJ:vices is greater than the disutility

associated with disturbances to 'the e!Tlvironment. Once the

marginal utility of consumption levels off with the resulting

disutility, the system shouldlllove ' back to eqllilibtium. 32

'This disutility results from externalities which are ' the

"

' prl.va

. t e cos t s. 33 Oft en th ese

result of social costs

exceed i ng

externalities result from a firm producing at overcapacity

"

34

'

'

levels.

These externalities, or spillovers, include noise

'a~d , pollution of industry and the adverse effects upon

plants. Often the externalities are accidental and are

35

placed upon individuals who are unable to avoid their effeots.

.~

}\

II. Statutory and Judicial Responses

A. water Resources Council

Cost-benefit analysis is a well-settled theory, having

been used in ' a general way in the early part of the , century. 36

In the field of water resources development, it was first

noted in the Flood Control Act of 1936. 37 The Act recognized

that destructive floods:

constitute a menace to national welfare; ••

that the Federal Government should improve

or participate in the improvement of

navigable waters ••• for flood control

purposes if the benefits to whomsoever

the'y may accrue are in excess of the

costs, and if the lives and social securitY38

of people are otherwise adversely affected.

One economist has observed that the legal requirements

of the Act are impossible to meet becaus,e economic analysis

is not refined enough to measure all costs ' and benefits "to

whomsoever they may accrue," and furthermore, such an assessment

requires

Act. 39

sp~cific

methodology Which is not specified in the

The next development in the cost-benefit analysis for

water projects was the Proposed Practices for Economic

Analysis of River Basin Projects (1958), also known as the

Green Book. 40 This work was important because it defined

primary and secondary costs and benefits.

The Green Book was

soon superseded by Policies, Standards, and Procedures in the

Formulation, Evaluation, and Review of Plans for Use and

Development of Water ' and Related Land Resources,4l which ,

became the ,official adoption of cost-benefit analysis.

Senate Document 97 is detailed in its, definitions of

benefits (tangible benefits; intangible benefits; primary

benefits; secondary benefits)and costs (project economic

' costs; installation costs; operation, maintenance, and

replacement costs; ' induced costs; associated costs; taxes). 42

Standards of , measurement are given for each type of benefit

resulting from water projects,

inclu~:i;.ng:

(1) domestic,

municipal, and industrial water supply benefits,

benefits,

(3) water quality control benef~ts,

benefits,

(5) electric power benefits,

prevention benefits,

drainage benefits"

(2) irrigation

(4) navigation

(6) flood control and

(7) land stabilization benefits,

(9) recreation benefits. 43

(8)

This methodology

of measurement for water projects became the most sophisticated

of the resource fields.

Most importantly, the statement

provides for economic projections of the project on both the

regional and national economies. 44

The statement is not without shortcomings, however.

It

has been c 'r iticized 'as plac'i ng undue emphasis upon benefits

of a project by its preoccupation with the quantity of goods

and services produced. While ' mentionin,g economic. growth;

the statement provides no real analysis for this resulting

growth. 45

A later report of the Water Resources Council in 1971

overcame many of the difficulties of its predecessor by its

practical approach. The Proposed Principles and Standards

for Planning Water and Related Land Resources 46 0utline four

broad objectives which are to be considered in relation to

a water project: (1) national economic development, (2)

, environmental quality, (3) regional development, (4) social

factors. It should be noted at the outset that each area

requires the application of the "with and without" principle,

which requires the estimation of the beneficial and adverse

effects of a particular project after completing the project

and comparing these results ,with the situation existing if

the project were never constructed. The analyst is also aided

by the tables in the Proposed Standards which give examples

"of beneficial .and adverse effects of projects, as well as the

ramifications o'n the economic development of the area.

The first ob'jective of analysis, national economic

development, conserns' itsetf with the increase of goods and

services. ' These increases in economic efficiency are to be

balanced against the increase in environmental quality which

,

' would occur by decreasing the use of' r 'esources ordinari ly used

in the production of consumer goods. The adverse effects on

national eqonomic developme'n t are determined by measuring the

'economic value that the resources would have in alternative

uses, and while these externalities are difficult to measure,

they should be recognized.

The second consideration, environmental quality, requires

the measurement of the deterioration of environmental quality.

The Proposed Standards enumerate cla's ses of environmental entities,

such as wild andsceriic rivers, lakes, mountains,. and estuaries,

and with,i n each class there are factors , to , be , measured to

determine the detrimental effects, Le. (for es,t uarie8) the

,

.

size of the estuary, biological significance asa breeding

or feeding ground, and improvements. 47

The beneficial and adverse effects on regional development

constitute the next 'category of measurement. Beneficial

factors are increased productivity of goods and services, value

of output to 'users residing in the region as a result of

external economies or expansion ,of resource use, and additional

net income resulting from the project. Adverse effects include

taxation, external diseconomices (externalities), and the

displacement of resources.

The fouth class of effects are those social effects resulting

from a project, SUCh as distribution of wealth,or improved

safety (as provided by flood control, for example).

The P~oposed Standards also discuss the problems involved

in determining the life of the project and the discount rate.

The life of the project is to be the lesser of "(1) the period

of time over which the plan will serve a useful purpose considering

probable technological trends affecting various alternatiVes; or

(2) the point of time when further discounting of beneficial

and adverse effects will have no appreciable result on design.,,48

After determining the period of analysis, the discount rate

-is the average rate of return on private investments, including

taxation. 49

B. NEPA and the Courts

1\

Athough the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

does not explicitly require a cost-benefit analysis, the Act

does ,require that "presently unquantified environmental

amenities and values may be given appropriate consideration

_

.

, an d tec h

'

1 conS1. d era t'10ns. ,,50

in decisionmaking

along w1th

econom1a

n1ca

The legislative history, in discussing ,the duties of the

Cou-n cil on Environmental Quality (CEQ), lends substance to

the -use , of the cost-benefit analysis:

One way in which this [consideration of environmental

amenities] might be done would be to develop

a , sophisticated cost and benefit analysis in which the total (and often not strictly

economic) consequences of Federal activities

.~

may be assessed. The environmental

auditing function of the Council falls

squarely within the functions specified

in this subsection.5l

52

The CEQ Guidelines are of little assistance, however,

in defining what is required in such an analysis, but the

Guidelines do reques't that the Environmental Protection

Agency be consul ted , where water .quality s 'tandards have been

set. 53 And the Environmental Protection Agency, in its

'

proposed guidelines, which were later adopted, requires a

cost benefit analysis. 54

The courts first interpreting NEPA were reluctant to

,find a cost-benefit analysis invalid unless it was shown

that the actua'l balance of costs and benefits was arbitrary

or ' clearly gave insufficient weight to environmental values. 55

The court in Sierra Club v. Froehlk~~6 however, held

a more aggresive view in regard to the analysis, after finding

a deficiency in the determination of the costs by the agency:

' However, when the claimed ' ratio is

comprised, in part, of environmental

amenities which Congress has required

under current law to be given careful

attention and consideration, then the

courts have an obligation to act, where

necessary. The standard for judicial

review is the same as for 'other features

of environmental law, being one of

"substantial inquirYi"57 •

.,

~

The court in Sierra Club pointed out that no environmental costs

were considered but that in addition to economic benefits,

the agency claimed recreational benefits -and benefits stemming

from navigation, ' water 'supply, and salinity control. 58 And

in spite of a large increase in costs over the years, the

59

cost-benefit ratio remained the same.

'III. Cost-Benefit All,alysis and Water Resources I

An Evaluation

A. The Use of Economic Theory and Quantification

,

Many problems associated with cost-benefit analysis stem

from the use of economic theory. Cost-benenefit analysis

assumes that the market is perfectly competitive and that no

externalities exist, ' so that once there is ,a change in these'

assumptions, the analysis becomes less reliable. 60 The goal

of any projec,t is the maximization of nutional income, while

the constrained variable is represented by the budget of the

61

'

federal government.

The population, however, is not interested

in the absolute size of the Gross National Product but is

interested in the income distr'i bution 'a s .it affects them

,

'

62

personally.

And, while it it is recognized that some

bUd'g etary restraint must be taken into account, the restraint

used has a sizeable effect on the cost-benefit ratio.

If some budgetary' restraint is not defined, a project may be

constructed to an excessive scale, which will result in .,the

dec~ease of funds available ' for projects more economically

desirable. 63 And furthermore, two projects might appear

similar since they have equal benefits, even though there is

a large disparity in costs. 64

since the values employed in cost-beneft analyaio are

related to values iil the mark'e tplace, their validity assumes

that the ' present distribution of wealth and in,come in the

lI'arket is acceptable. If , the purpos'e of a project is to

raise water quality in an urban area, then the lower income

groups are the milin bElneficiaries siAde they live in the

cities; but if \~ilderne5s preservation are the primary benefitl\,

then benefits are overstated because t.hey · flow to those in

,

65

.

higher incomes.

Thus, the task of economic evaluati.on is a complex one:

The water resource economist now frequently

faces a truly imposing array 'of problems

evalua ting water resources whose market

purchas e at best generates only indirect

indications Of / the relative value people

place on them; tra(:ing and evaluating

complex ' interdependencies on sys 't ems e ,f fects,

often over very large geographical areas;

and helping to guide decisions involving

great uncertain TY due to the rapid ,pace of

economic and tAchnical data. 66

Much of this difficulty results from the information

included ' in the analysis. Cost-benefit analysis has heAn

criticized as containing a bias of the analyst, which is aften

the government. 67 The statements prepar.ed by the government,

which often distort aetual benefits, seem to support this

criti~ism.68 These conscious evaluations, however, are

' reflected in the analysis. But often a proj e ct produces

results that were never ' anticipated when the analysis was

prepared. If the market fails to provide fol;' all of the

alternatives, then it is impossible to obtain the most

efficient analY6is. 69 The analysJs, therefore, may demonstrate

that welfare has increased, but it does not indicate whether

the m~ximum benefits have been achieved. 70

The use of economic analysis requires the quantification

of costs and benefits into monetary terms in order for the

, resul ts to be AXp,r esse'ct as a mathematical t:atio. ,Monetary

amounts are placed on' environmental ame nJ.tit>s as a measure' of

their value. This uSe of the price system as ' a means of

evaluation, howevp.r, is complicated, since many benefits an~

costs ' connected with environmental ' issues have no market

value, such as "the joys of ' a free flowing stream.,,71

,Kenneth Boulding, a lloted economist, believes that human

values can be reconciled jand comput"'c;l ,.with economic values. 72

The final result of the analysis is a single mathe~aticai

figure. Finding a ll11mez:ical expression to represent the

"standard of 1 iving, ',' for example, presents the same pZ'ob lems.

The many facets of environmental quality make it impossible

to interrelate all of the criteria, much of which i~ subjective,

and produce a measure of overall environmental quality to

fit into the cost-benefit ratio. 73

Assuming that environmental all\onities can be quantified "

the problem is easier when the analyst is deciding among

alternative programs; theoretically, at least, errors 'are

consistent in all of the 'factors and will hI'! reflected equally

in each. In Ii broader sense, even if there ~s an a.bso~ute

measure available in tho resources field,

the problem remains

of comparing the benefits and costs in the , resources field with

' those of other fields of government expenditures in order to

arrive at the most effi 'c ient use of government funds. 74

Despite the complexity and arbitrariness of cost-beneflt

analysis,

quantific~tion

forces the analyst to carefully

examine all possible alternatives, to account responsihly for

his own preferences, and to perceive the relations between

variables and

mar~et

restrictions in economic analysis.

The

preparation of the analysis serves an important function in com75

pelling an interdisciplinary study of the proposed project.

B. Measuring

Ben~fits

and Costs

Hany of the limitations of cost-benefit a,n<1lysis rest

within the inherent restrictions of economic analysis in

measuring benefits and ebsts.

Since the economist can only

accurately estimate short run costs,76 the analysis will

overstate costs and unde'rstate benefits.

For example, the

short term solution of placing a device on an existing plant

to abatA pollution is more expensive than 'a long term proposal

of designing a plan't for pollution abatement.

As a result,

long term costs may be omitted, and the benefits which result

from expenditures may be estimated despite a reliable method

'

t 10n.

'

77

,

O'f quan t'1 f 1ca

.,

1. Benefits

A water resource project may prbduce several benefits

which have counterparts in the mark et system.

In projects

for irrigation and flood control, ,the analyst can determin e

how much the fa rmer, has i llcre'a sed his ' productivity by c omparing '

yields before and afl:er the project. 78 or the amount of flood

damage that would have resulted to 10'Ncr riparinn landowners

in the abs e n ce of a dam. 79

In other instances the

, benefits are eas i ly identifiable

,

'

but are very di.Cficult t p measure, such as the economic

advantage which industry gains as a result of a decrease in

treatment costs 8 2r the economic advantage wh i ch il1dust ,r y 'gains

8l

from the greater availabi f ity of recreational servic;:es.

In regard to certain eecondary benefits, it i3 often possible

to d~termine tho economic effects of a project in a regional

analysis, but it is beyond the capabilities of cost-benefit

analysis to determine the economic ramifications of a project

on the national economy, even though admitt,,,J1y the national

income is increased by tho~:e projects. 82

And in the water resources field; it is not only difficult

to measure certain intangible benefits but to develop causal

relationships I these benefits include:

land values,

(1) increases in private

(2) increases in employment,

(3)

profits o.f

businesses dealing with water recipients, (4) value of water

above that paid by the recipient. 83 De5pite th£> difficulties

of evaluation of water quality improvoment, recreation, and

improved industrial and municipal water supply·, the government

has increased i ·ts reliance on such benei ts in justifying

projects.

The area of recreational benefits comprises an increasing

justification for the development of water projects. 84 The

usual procedure for evaluating outdoor recreation is by means

of a value between $0.50 and $1.50 per man-day for general

Qutdoorrecreation an.d between $2.00 and $6.00 per · man-day

for speci.alized · ·outdoor recreation. 85 These values of rec- ·

reational benefits have been criticized because they are

. arbitrary and fail · to take intoconst~eration such factors

as the proximity of· the . population to reservoirs offering

recreational benaf£ts. 8& The~e recreational benefits are

also claimed without allowing for the costs to free flowing

.

.

87

stream recreat10n.

Th1 visitors t.o these recreational areas

may be few in number, but. since they are considered high priority

visitors, . the benefits may be overstated.

On the other hand,

there may be social benefits in encouraging outdoor recreation.

The individuals who attend these recreational projects pay

littie or nothing for the privilege, so that they may benefit

. d t 0 pay. 88

more th an 1. f th ey ware reqlure

As noted . above, the willingness to pay principle has been

used in cost-benefit analysis to d~t~rmine · the va.l ue of benefits:

The mere use of this criterion gives preferential r.ights to

those who are using the ' environment for waste dispoSlll,S3

Then the analyst must make a comparison of the benefits

accruin9 to different persons, 'l'he usual procedure is to

,a dd the ben'Jfits of all people with each person given an

equal '''<"light. EVfln with this procedu're, ther" is a ,U fficult

valUe judgment required to make ,these interpersonal comparisons. 84

How much a person is willing to pay for benefits is

often determined through a referendum approach or opinion

polll3. SAveral problems may arille in this process of

questioning indIviduals. If the individual expects to be

charged for what he is willing to pay, then it is logical to

iUlflume that he wOll,ld Hant to pay the least possible amount.

If he then undervalues his willingness to P."'I.Y, he will expect

to pay less. On , the other hand, if an indi.vidUal kn('ws that

his payments for a proje1t w.o'lld be small and that the project

would be financed by the federal 90vernment, there is tendency

to

overstat.~

Uti!

,

t.'

construc10n

0f

benefits in an, effort to encourage tht!

1

,ft5

tIe

proJect.

'

, "

The willi,n gnElss to p~y approach may also be undp.restimated

in ano,ther way, Since 'the , preservation of the environment

is an important part of the real income of many indivi.duals,

the amount of compensation these individuals would require

if future generations were to be dep.f~ved of environmemtal

amenities would be much greater than the w,i llingness to pa~'

for the present benefits of the pr.oject. U6

,In adclit,ion to ' 'the concept of wi.llin-"ness to pay, benefits

may be valued by alternative c'o~t.s, ~lhich are the costs of

prol1idi.ng comparable output by means of the least expensive

'alternative. ' Th'lS, the val,ie of b~nefits of a federal power

project are equated with the CO'!lts of a prj,v,d-,e utility's

providing the same level of output. S7 Determing benefits by

means of alternative costs is 'not only employed in' power

projects I but projects for municipal ~later supply and

navigation. SS

This, practice of alternativEl costs is often misleadin,],

i.t is based on t.hE. assumpt.ion that soclety would 'mdertake

to provide · t.hose. benefits with th,;. alter·n ative meana. R9

Sinco tho project. may involve coJ.loctive goods, i .t. has been

noted that the private sAC!tor would ·have never undertaken the

proj~ct due to .l.t8 prohibitive costs.

2. CO" ts

From a theoretical standpoint. costs are easier to

compute than bonefits. It is not difficult·. 1.: 0 e .. timate how

much it ,~ill cost to construct and . operate a treat.ment plant.

But the major problem in estimating future costs consists in

predicting the amount of pollution control and the effects of

technological changes. 90 Thp. analyst needs i.nformation which

will indicate the costs of industrial praco.sHs at each level

·. ~f effJ. uen~dischargo, · for such information isnecassary to

the planning of water quality cont.r .ol fly·stems. 91

ilS

The cost-benefit ra~ios can be altered by the costs ·

.

included. . In many ratio~, indirect benefits are e~umerated,

but indi.rect costs are excludod; t.hus givin'] a more favorable

ratio. 92 B'lt ·the Corps of 1>.l Igineers, .accordin.,)" to ·some

·economists, is understatirtg its ratios by placing local

contr:i.butions of cash, land, and easements on the aide of

projed t co~ts instead of considering them as be nefits. 93 .

Since the cost concept includes consideration of a.lternative

costs, the agency may tend to ·disregard these 10wAr cost

alternatives. In most cases, 3in .~~ ·I::lie federal water planning

agancy is also involvec in th~ construction of projects,

there is Hvid'3nce t.hat these agenci(~ s "re- biaaed in favor of

·alt.ernatives requiring construction. These ;;'9E"",1.eS are

criticizf.'d for fa.i.Jing to consider measures not involVing

con"t.1"'.lC·r:ion, ,;uch · as the ·regulation of a flood pla·in instead

of a dam. Tn the area of wal·.er quality improvement, those

agencies have neglected sunh alternatives as in-plant treatment

or infrequent degradation · of water quality.94

The agency which d.isregards ·these alternative costs often

ignores .the external.i.ties resulting from a project·, such as

the soci",l costs .of ·taxation. ·The federal projects, of course,

require funds which are obtained through taxation; i f the

taxation is great, misallocations of resources may result,

.

9C,

.

often as a consequence of inflation • . . These advserse effects

rosul ting from taxation inay be minimi zed in projects which

produce th~ir own revenues . In these projects, the costs

arA confined to the amount borrowed from the government, so

that the oretically tax cl.lts will result. 96

·C. Forecasting

The th~ory of cost-benefit analysis rests upon the

assumption that future conditions can in some way be predicted

with reasonable accuracy. The seC"!ondary benefits of a water

project assume . that there will be " . suffici~nt demand for

the goods and service.s prodti.ced • . Most studies involving

project analysis rely upon the posulate that the demand for

industrial anct municipal waste will i ·ncrease at a rate

proportionate to population growth or economic change.

Behind this assumption is the belief th.a t the . demand for

water is inelastic, '.'hieh is incorrect according to economic

theory.9"l

Not only may the mf rkets disappear, but requil'ed inputs

may become scarce, population patterns may change, operating

.costs may increase, or com·p eting demands for land may intervene.

Demand for a project in th,~ present may alao shift as a

result of technological challges wh:l.cb render certain

industrial proce'lses obsolete. 9 8 .. .,

Influenced by future economic conditions, forecasting

also involves speculation as to the useful life of a project

and a discounting of the costs and benefits in order to

arrive at the present value. An increase in the nominal life

of a project has a considerable impact upon · the ratio if a

low discount rate is used. 99 But the impor.tanee of the

life ·of the project may be diminished by the practice of

giving time per.iods in th .. future less importance than the

present by means of the discount rate. lOO

The selection of the d ~ scount rate requires speculation

. . .. .

101

of future demand and technological changes. .

Inmost

government projects the discount rate ha s been the average

rate 'a t which the government can borrow. which is usually

between five and six per cent.

This rate has been defHnded

on the grolind that it is the social cost of capital and ill,

the retul:1I realized' on capital invested in alternative uses.

The rate is also supported as being realistic since the

government is able , to bor.row at long tern, government bond

r~tAs.I02

The use of this inlerest rale, however, han heen

critir:::ized a:l (~xa'.:lgerating the value of a project by under' stating the costs which are ill<.lurred in the private 'sect:or

~s a rcsult of risks and corporate taxes. 103 The same

project in the private s<)ctor, to be deemed effici e nt, wOllld

require at least a lHn per cent discount rate. 104 Thu3,

projects which are efficient in the public ucctor would be

uneconomical if attempted hy private firnls, and as a result,

there is a misal'location of resources.

It has been argued

that.]. discount rate based upon alternative costs would be

a mo ,t'e accurate measure .105

The pI'oblBRt of discount rates is particularly acute in

the de'lelopmoni: of willl3r resources. In most water projects

majo,r i ty of expenses are incurr~d in th .. early yeac.l of

project, and benefits are spread over a long period,

twenty or fifty years. Thus, a low interest rate makes

project seem favorable, while a high rate lowers the

. e ff"l.Cl.ency . 0 f th e proJec

. t • 101; r 1\ many proJects,

.

economl.C,

lohe

the

say

the

the higher rates would not have caused the ratio' to result

in a value less than unity, but it woulcfhave caused a

decrease in the level off development or a considt!ration of

' . ,

107

ot h er a 1. ternat1ves.

IV. Recommp.ndations

The theory of cost-benefit analysis is based upon the

economic concepts of marginal costs and benefits, Which .

have their normal application in market behavior. The

limitations of ' using this economic theory as a rigid rule,

,without qualifications, must be recognized. lOB

The necessity of value judgments will cause the costbenefit ratio to reflect the point of view of its analyst.

AS.more consistent ' procedures are developed, the problem of

bias will diminish" but the analysis should remain flexible

enough to allow amendments if it proves unreliable. 109 And

if a single ratio tends to be misleading, then the analysis

' could be prepared as a partial quantification with qualitative

effects being stated in an addendum. ,

The end result of a cost-benefit analysis is a numerical

, ratio.

As noted above, the comparisons of the ratios , of two

, projects will fail to take into account the relative costs

of each project. 110 This misleading aspect of the analysis

is

~liminated

if the analyst assumes that capital resources

are defined by, the federal budget.

The purpose of ' cost-benefit

analysis is to maximize the returns on public funds, so the

,

analysis ' shouldseperate capital costs fr'om operating costs

and exclude these operatirigcosts.

Ih this way, projects

having the highest ratio will result in the maximum net

111

benefits.

The absolute nature of the ratio must be subordinated to

its relative economicevaluation. 112 Thus, when two projects

are to be compared, there must be corresponding entries for

each benefit and cost.

The analysis ' can be prepared as a

"

.~ such procedure allows

balance sheet with analagous entries;

greater objectivity and accountability for value' judgments.

The costs enumerated must be consistent ,with one another in

, order to avoid "variations of capital intensity."

f

'

must also possess this same type of uniformity.

Benefits

And, lastly,

the life span of the project must be approximately the same

to avoid disparity in the ratios.11 3 ' ~f s~ch internal

consistencies are maintained by the analyst , then the errors

which result from economic measurements will be reflected in ,

all of the ratios for, a particular project and will produce

greater uniformity.

Even if the relative aspects of economic

analy~is

are

stressed, the project finally chosen may fail to allocate

resources in the most efficient manner.

As a result, a

seperate study of marginal net benefits must be made; the

marginal net benefits of the project must be equal zero fpr

the maximum benefits to be realized. At a certain point,

a project has maximum benefits which will be decreased by

a change in the size of the project, I.e. lowering or raising

the height of a dam. This type of analysis has , been undertaken

by the Corps of Engineers in studying the changes in navigation

,

channel depth.

But in most instances the agencies, which

favor construction, tend to build projects to utilize all

available resources to the point where incremental costs

greatly ou'tweigh benefits .114 ' The use of multi-purpose

reservoirs has also become a dominant feature of water

resource planning.

,And Yet i t i s often more efficient to

locate a single purpose

~eservoir

close to an urban area

than to develop a multi-purpose reservoir further away from

11S

those areas.

The economic criterion provided by cost-benefit analysis

serves well to justify projects as economically efficient,

but it revea1s ' little about the subsequent effects of those

projeCts.

,With a few alterations, ,an input-output analysis

can provide a means for determinihg the effects of a project

by placing waste disposal facHitteli jpn the input side.

The

effects on production as a result of these facilities can be

,

116

noted, as ,well as the effects of alternative proposals.

This input-output analysis points to the deficiency of the

cost-benefit analysis in stressing increases in national income

as its goal instead of stressing multiple objectives, such as

the preservation of flowing water resources. ll ?

The problem of forecasting future demands is an important

factor in the anal~sis of any ~roject, and cost-benefit analysis

should improve period analysis rather than develop new ideas

1

of what constitutes secondary benefits and costs. l 8 And

since technology often renders a project ' obsolete, the analyst

should eonsider alternative de~ign8 which allow , for these

changes, such as less durable structures or general purpose

designs which can be altered. 119

Discount rates determine present value, but the rates

used fail to provide

inf~rmation

to begin a project.

For the present year and several

for determing the best year

succeding y ears, an estimate of net benefits for each year

should be made.

If the estimates are then discounted to , the

present year, the year which indicates the greatest amount

of net benefits, or largest ratio, is the optimal ye ar to

' t he proJec

' t • 120

b eg1n

The discount rate applied to federal projects has been

underestimated, so the discount rate should include such

factors as economic risk and corporate taxes, both of which

are met by private developers. l2l since the public is taxe d

to . provide funds fo.r these projects, the national income is

maximize d only in those instances where a public project will

be as good an investment as a private undertaking. l22 And

frequenl:t:'Iy; as a result of this taxation, there is a shift

in the distribution of ihcome.

To avoid undue shifts to those

in lower income groups, the estimate of the benefits should

be measured in relation to those individuals with incomes

close to the mean.

Such a correction would tend to lower the

ratio of projects · which serve primarily to benefit those in

upper income l .e vels .123

.~ 1t

The final effectiveness of any cost-benefit ratio, .. no

matter how refined the economic procedures, depends upon the

containment of political forces, which may override the

determinations of the analysis and encourage the implementation

of undesirable projects. l24

V. Conclusion

Cost-bene fit analysis performs well as an indicator of

economic efficiency.

Problems are encountered when the

analysis is used to compare different projects .; in which

intangible benefits and costs are measured.

Valu.e judgments

must, of necessity, be made when the price system has

failed to provide for many of the results of a federal

project.

These · value judgments lead to certain abuses

)

.

by the analyst. such as f ·ailure to consider alternatives

with lower costs or alternatives more susceptible to

changes in technology.

Determining the technology of the future, as well as

its market demands, requires pr·e dictions by the analyst,

who needs this information to calculate the discount rate

and the life of the · project.

Again, the economic analysis

needs refinement, but the: analyst must strive to avoid

inflating the benefits.

Furthermore, the destruction of the environment must

be recognized as asocial cost, despite difficulties in

quantification.

In the field of water resources, the

Proposed Standards have implemented a practical approach

with specific examples of adverse effects, which should

result in greater consistency among results.

Until procedures are further refined, cost-benefit

analysis must be recognized as what it is - economic

theory.

The analysis may not solve all problems in the

water ' -resources field, but it does force the decisionmaker .

to evaluate the project carefully with asystematic

methodology.

Footnotes

lR. Leftwich, The Price System and Resource Allocation

9 (4th ed. 1970).

2 Id • at 335.

3For a discussion of least-cost combination, see

R. Leftwich, The Price System and Resource Allocation

139-41 (4th ed. 1970).

l29-~1,

40 . Eckstein, Water Resource Development 38-40 (1958),

S. Nath, A Reappraisal of Welfare Economics 164 (1969).

5w• Ramsay & C. Anderson, Managing the Environment 86-87

(1972) •

6E • J. Mishan'; Cost-Benefit , Analysis 316

(1971).

7Id • at 316.

8 Id • at ,317.

9Note , Cost-Benefit Analysis and the National

Environmental Policy Act of 1969, 24 Stan. L. Rev. 1092, 1099

(1972) •

10see generallyR. Leftwich, The Price System and Resource

Allocation ' 195 (4th ed. 1970).

. ),

ilCiriacy-wantrup, Cost-Benefit Analysis and Public

Resource Development,in Economics and Public Policy in

Water Resource Development 12 (S. · Smith ed ~- · 1964).

12

J. Sax, Water Law: Planning and Policy, ', CaSes and

M~terials 30 (1968).

13A• Reitze, Environmental ,Law Introduction-30 (1972).

l4 Id •

l5J- . Sax,

' Water Law: Planning and Policy, Cases and

Materials 29-·30 (1968).

16Hammond, convention and Limitation in Benefit~ Cost

Analysis, 6 Nat. Re"!!. J. 202 (1966).

17J~ Hi r shleifer, J. De Haven, & J. Milliman, Water

Supply 137 (1960).

18 J. Sax, Water Law: Planning and Policy, Cases and

Materials 30 (1968).

19Note , Cost-Benefit Analysis and the National Environmental

~olicy Act of 1969, 24 Stan . L. Rev. 1092, li91 (1972).

20

"

For a discussion of the applicability of these methods,

see O. Eckstein, Water Resources Development 65-69 (1958).

21proposed Practices for Economic Analysis of River Ilasin

Projects, Report of the Subcommittee on Evaluation Standards

to the Inter-Agency Committee on Water "Resources (1958).

22 Id •

23ciriacy-wantrup, Cost-Benefit Analysis and Public

Resource Deve lopment, in Economics and Public policy in

Water Resource Developmen~ 15-17 (s. Smith ed. 1964).

24

Id. at 12.

25 E • J • Mishan, Cost-Benefit Analysis 316 (1971).

.

26 J • Hirshleifer, J. De Haven, & J. Milliman, Water

Supply 86-87 (1960).

)

27 M• Spe ncer, Contemporary Economics 361 (1971).

S"pencer gloves this sJ.mplified example "of alternative costs:

To a student, the cost of getting a full time college

education includes not only his outlay costs, i.e. costs for

tuition and books, but also the income he fore"goes by not

working full time.

28 R . " Leftwich! The Price System and Resource Allocation

144 (4th ed. 1970).

" 29

See generally Leontief, JThe Review of Economics and

Statistics

262~69

(1970).

30

.

Other uses of input-output tables include the

establishment of priorities in environmental polici, the

impact of ecological technology on economic and ecological

systems in general, and the measurement of alternative

costs in a particular ecological stabilization system.

W. Ramsay & C •. Anderson, Managing the Environment 80-81

(1972).

31 0 • Eckstein, Water Resources Development 52-53 (1958).

321'1. Ramsay & C. Anderson, Managing the Environment

85-86 (1972).

·33 The economic theory involved in externalities is

discussed in R. Leftwich, The Price System and Resource

Allocation 195 (4th ed. 1970).

341'1. Ramsay & C. Anderson, Managing the Environment

88-89 (1972) .

35E.J.Mishan, Cost-Benefit Analysis 102 (1971).

36For a discussion of early statutes and decisions

which employed .what · amounted to cost-benefit analysis,

see Tre1ease, Policies for Water Law: Property Rights,

Economic Forces, and Pub1io Regulation, 5 Nat. Res. ,J. 1,

17-18 (1965).

37 Act of June 22, 1936, Pub. LI, 1.No. 74-738,49 Stat.

1570.

38 Id •

390 • Eckstein, Water Resource Development 47-48 (1958).

40proposed Practices for Economic Analysis of River Basin

Projects, Report of the Subcommittee ' on Evaluation Standards

to the Inter-Agency Committee ,on Water Resources '(1958) .

41Water Resources Council, Policies, Standards, and

Procedures in the FormulatIon, EvaluatIon, and Review of

Plans for Use and Development of Water and Related Land

. Resources, S.Doc. No. 97, 87thCong., 2dSess. (1962).

[hereinafter re'ferred to as Senate Document 97)

42 Id . , at 8-9.

43 Id • at 10.

44 Id • at 7.

45 Fcilz ,' .Public and Private Investment in Resources

Development, in Land and Water, Use 333-34 (W. Thorne ed.

i 1963) •

. 46

Proposed Principles and Standards for Planning Water

and Related Land Resources, 36 Fed. Reg. 24144 (1971).

(hereinafter referred to asPrciposed Standards)

47 Id • at 24160.

48 Id • at 24167.

49. Id • at 24166.

50National Environmental . Policy Act, 42 U.S .C. ~ 4332

(1969) •

, 51

H.R. Rep. No. 91-378, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. 2751,

2760 (1969) •

,

.. S2 CEQ Gliidelines, 36 Fed. Reg. 7723 (1971).

53 Id • at 7724.

54Environmental Protection Age99¥' Environmental Impa c t

Statements, Procedures for Preparation, 37 Fed. Reg. 883

(1972) •

55

.

EDF v. Corps of Engineers, 470 F.2d 289, 300(8th Cir.

1972); Calvert Cliffs' Coordinating Comm. v. United States

A.E.C., 449 F.2d . 1109, 1115 (D.C. Cir. 1971).

56sierra Club v. Froehlke, 359 F. Supp. 1289 (S.D, Tex.

1973) •

57 Id • at 1365.

58 Id • at 1368 •

. 59 Id .' at 1369.

60 R • Leftwich, The Price Syatem and Resource Allocation

'195 ' (4th ed. 1970); Ciriacy~Wantrup, Cost-Benefit Analysis

and P,ublic Resource Development, in Economics and Public

Policy in Wat.er Resource Development 12 (s. Smith ed. 1964).

61The effects ofbadgetary restraint are discussed in

O. Ecksteiri, Water Resource Development 70-80 (1958).

62

R. Hav e man, Water Resource Investment and the Public

Interest 98 (1965).

63 0 •

Eckstein~ ,

Water Resource Development 62-63 (1958).

64Hammond, Convention and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Anal¥.si s , 6 Nat.

65Freeman,

Re~.

J. 195, 202 (1966').

Dis~ribution

of Environmental Quality, in

Environmental Quality" Analysis 248 (A. Kneese & B. Bower

' ed. 1972).

66Kneese, Economic and Related Problems in Contemporary

Water Resources Management,S Nat. Res. J. 236, 237 (1965).

67 Bohm , A Note on the Problem of Estimating Benefits

,from Pollution Control, in Problems of Environmental

Economics 85 (1972).

6BNote , Cost-Benefit Analysis and the National Environmental

Policy Act 'of 1969, 24 Stan. L. Rev. 1092, 1104 (1972).

69coddington, Some

Limitation ~

bf Benefit-Cost Analysis

in 'Respect of Program.mes witl! Environmental Consequences,

in Problems of Environmental Economics ' 120 (1972).

70Trelease, Policies for Water Law: Property Rights,

Economic Forces. and Public Regulations,S Nat. Res; J. 1.

12 (196 5) .

71

'

W. Ramsay & C. Anderson, Managing the Environment

73 (1972).

72See Boulding, The Basis of Value Judgments in Economics,

in Human Values and Economic Policy 64-71 (s. Hook ed. 1967).

73 Bohm , A Note on the Problem of Estimating Benefits

from Pollution Control, . in Problems of Environmental Economics

85 (1972).

74

.

O. Eckstein, Water Resource Development 50-51 (1958).

' .

75 C ~r~acy-Wantrup,

.

Cost-Benef~t

Analys i s and Public

mesource Devclopment, in Economics and Public Policy in .Water

RGsource Development 11 (S. Sm~th ed. 1964).

76Assuming, of course, that long t<;lrm total costs are

lower than short term average total costs.

77 LaVe,

.

A~r

'

Po.1 1

ut~on Damage: Some

. ff~cult~es

'

.

.

~n

D~

Estimating the Value of Abatement, in Environmental Quality

Analysis 238

(A. Kneese & B. Bower ed. 1972).

78The "with and without" principle refers to the procedure

in which the project is analyzed in terms of economic

change after the project has been completed and in the

situation existing if the project was never constructed.

See O. Eckstein, Water Resource Development 51-52 (1958).

79 O. . Ec k ste~n,

.

Water Resource Deve lopment 52-53

(1 958.

)

80Kneese, Ec onomic and Related . Problems in Contemporary

Water Resources

I~anagement,

81 A.Fre e man. R.

5 Nat •. Res. J. 236, 246

(1965).

& A. Kneese. The Economics of

Environmcnt<0. Pohcy 109 (1973).

." ,~

Haveman~

82Harnrnond. Convention and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Analysis, 6 Nat. Res. J. 195, 212-13 (1966).

83 J.

.

H~rs

hI'

e~ f er. J. De Haven, & J. Milliman. Water

Supply 162 (1960).

84 Kneese,

.

Econom~c

d P ro

. bl ems ~n

. Con temporary

an d

Reiate

Water Resources Management, 5 Nat. Res. J. 236, 242 (1965).

8S A • Reitze, Environmental Law Introduction-30 (1972),

Interagency Committee on Water Resources, H.R. Doc. No. 276.

App. V (1965).

86Kneese, Economic and Related Problems in Contemporary

Water Resour c es Management, 5 Nat. Res. J. 236; 2 42- 4 3 (1965).

87 S~erra

'

'

C1 u b v. Froehkle,

359 F. Supp. 1289, 1379

(S.D. Tex. 1973); EDF v. Corps of Engineers, 325 F. Supp.

749, 759 (E.D. Ark. 1971).

88

'

Tolley, Future Economic Research on Western River

Resources - Wi th Particular Reference to, California,

5 Nat. Res. J. 259 :, 271-72

(1968).

89 Note , Cost-Benefit Analysis and the National Environmental

Policy Act of 1969, 24 Stan. L. Rev. 1092, l.105 (1972).

90 A. Freeman, R. Haveman, & A. Kneese, The Economics of

Environmental Policy 10 (1973).

91Kneese, Economics and Related Problems in Contemporary

Water Resources Management, 5 Nat. Res. J. 236, 246 (1965).

92Harnrnond, Convention and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Analysis, 6 Nat. Res. J. 195, 212 (1966).

93 0 . Eckstein, Water Resource Development 65 (1958).

94 Fox , Efficiency in the Use of Natural Resources:

Attainment of Efficiency in Satisfying Demands for Water

Resources, in American Economic Review 190; 201, 205 (May,

1964) •

95 0 . Eckstein, Water Resource Development 49 (1958).

96 Id. , at 50.

97 F,o x, Efficiency in the Use of Natural Resources':

Attainment of Efficiency in Satisfying Demands for Water

Resources, in American Economic Review 190, 201, 205 (May,

1964) •

98 J . Hirsh1eifer. J. De Haven, & J. Milliman, Water

Supply 160 (1960).

99 '

Fox, Eff'ici e ncy in the Use 'of Natural Resources:

Attainment of Efficiency in Satisfying Demands for Water

Resources, in

1964) •

~erican

Economic Review 190, 201, 205 (May,

lOOJ. Hirshleifer, J. De Haven, & J. Milliman, Water

Supply 160 (1960).

101Fox, Efficiency in the Use ' of Natural Resources:

Attainment of Efficiency in Satisfying Demands for Water

Resources, in American Economic Review 190, 201, 205, (May,

1964) •

102R . Haveman, Water Resour'c e Investmen,t and the Public

Interest 9B-99 (1965).

103Hammond, Convention and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Analysis, 6 Nat. Res. J. 195, 211 (1966).

104 J . Hirshleifer,

De Haven, & J. Milliman, Water

Supply 160 (1960).

105

.

,

Hammond, Conventl.on and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Analysis, 6 Nat. Res. J. 1.95, 211 (1966).

106 J . H

' ~rs

, hl e1' f ar,' J . De Haven, & J; ' Milliman, Water

Supply 160 (1960).

107 F ox, Efficiency in the Use of Natural Resources:

Attainment of Efficiency in Satisfying Demands for Water

Resources, in American Economic Review 190, 201,205 (May

1964) •

10BHammond, Convention and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Analysis" 6 Nat. Res. J. 195, 201 ,<:1.\966) •

109 Id • at 214.

110For the view that the relative factors of projects will

remain the same, despite errors in forecasting, seeO. Eckstein,

Water Resource Development 50 (1958).

lllHammond, Convention and Limitation in Benefit-Cost

Analysis, 6 Nat. Res. J. 195, 202

(1966).

112 0 • Eckstein, Water Resource Development 50 (195B).

113 Id • at 55.

114 J • H!.rshleifer, J. De Haven, & ,J. Milliman, Water

Supply 160 (1960).

l15Kneese, Economic and Related' Problems in Contemporary

Water Resources Management, 5 Nat. Res. J. 236, 242-243

(1965) •

l16coddington, Some Limitations of Benefit-Cost Analysis

in Re spect of Programmes with Environmental Consequences,

in Problems of Environmental Economics 121 (197,2).

l17 R . Have man, Water Resource Investment and the Public

Intere st 98 (1965).

ll8Ciriacy-wantrup, Fast-Benefit Analysis and Public

Resource Dev e lopme nt, ~n Economics and Public Policy in Water

Resource Developme nt 18 (S. Smith ed. 1964).

119 p ox, Efficiency in the Use of Natural Resources:

Attainment of Effi6iency in Satisfying Demands for Water

Resources, ' in American Economic Review 190, 201, 205 (May

1964) .

l20Tolley, Purure E60nomic Research on Western River

Resources - With Particular Reference to ' California, 5 Nat.

, Res. J. 259, 271 (1968).

l21 J • Hirshleif e r, J. 'De Haven,

&

J. Milliman, Water

Supply 160-61 (1960).

l22 R • Haveman, Water Resource Ihvkstment and the Public

Inter e st 101 (1965).

123preeman, Distribution of Environmental Quality, in

Environmental Quality Analysis 248-49 (A. Kneese & B. Bower

ed. 1972).

124p o 1 z, Public and Private Investment in Resources

Development, in Land and Water Use 334 (W. Thorne ed. 1963).