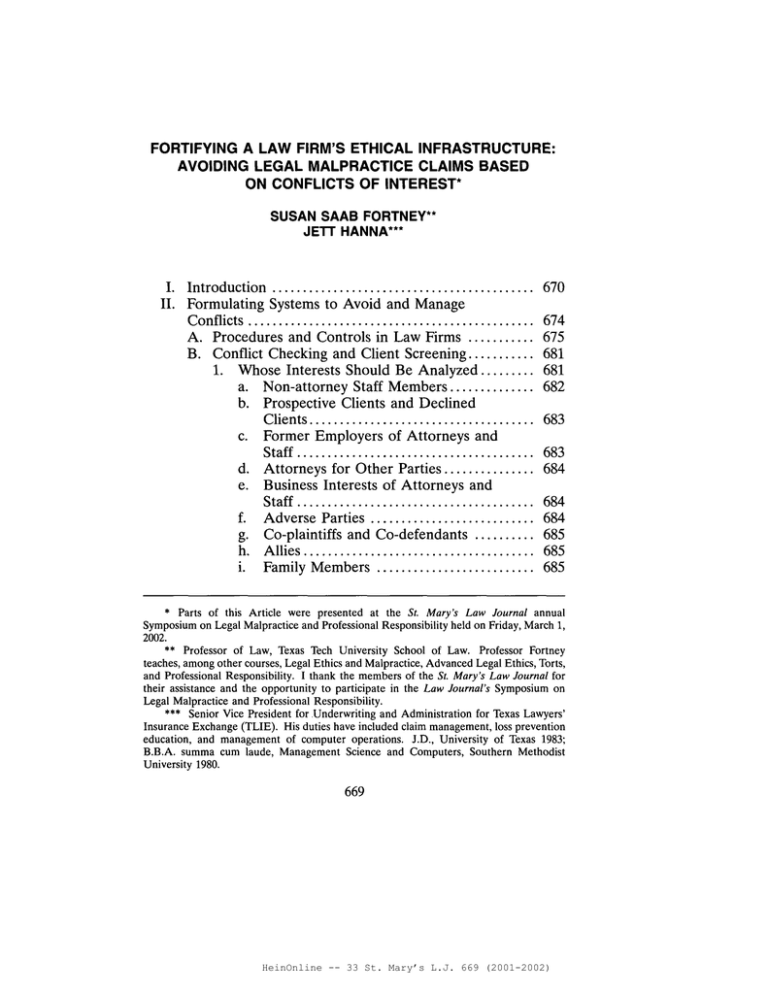

FORTIFYING A LAW FIRM'S ETHICAL INFRASTRUCTURE: AVOIDING LEGAL MALPRACTICE CLAIMS BASED

advertisement