Document 13107779

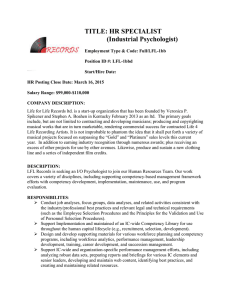

advertisement