THE CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS IN THE CONTEMPORARY CORPORATION: Markus Menz

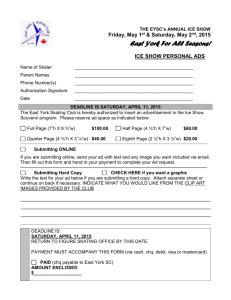

advertisement