Financial Governance and Transnational Deliberative Democracy

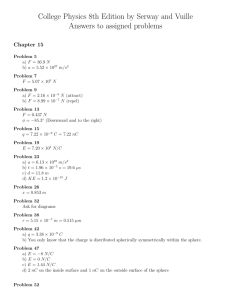

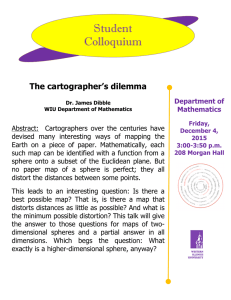

advertisement