Racist Name Calling and Developing Anti-Racist Initiatives in Youth Work

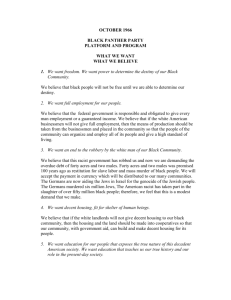

advertisement