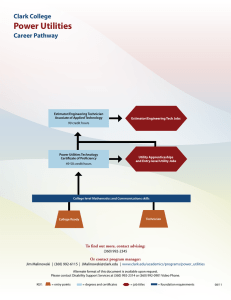

American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials (A.A.S.H.T.O. )

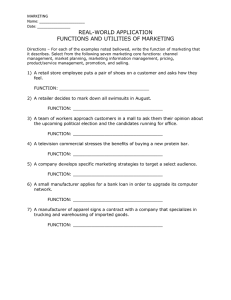

advertisement