The Role of Incentives for Opening Monopoly Markets: Comparing

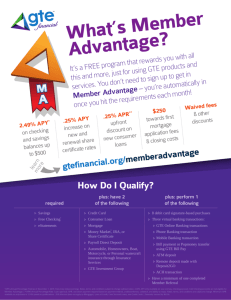

advertisement