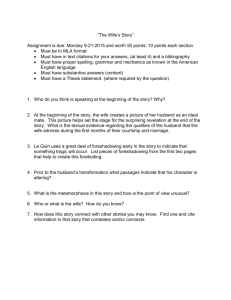

RETIREMENT AND THE INCEPTION-OF-TITLE V.

advertisement

RETIREMENT BENEFITS

AND

THE INCEPTION-OF-TITLE DOCTRINE--BUSBY V. BUSBY

MIKE THOMAS

RETIREMENT BENEfITS

and

THE INCEPTION-Of-TITLE DOCTRINE--BUSBY V'. BUSBY

Having its derivation in the law of Spain, the Texas communit1 property system has survived as ,one of the ' fundamental principles of property

law in

~exas. 1

In the Constitution of 1845 , drafted when Texas became a state in

..

the Union, the wife's separate property'was defined as "all property both

\

real and

personal. .• owned by her l:iefore

marriage, and that pcquired. after-:

.

\

'

wards by gift, devise', or descent. ,,2

This constitutional definition has

remained virtually intact to the present,. 3

However, the statutory definition has gone through a few attempted

,

'

,

changes. These changes . which appeared ,in 1917 and were enacted in 1921

.

intact , attempted to charActerize the rents ,and revenues from the wife's

"

separate property as separate property.

In Arnold v. Leonard

4 the Texas

Supreme Court held thi s to be unconstitutional, with the resultant effect

that the Constitutional qefinition

of what

,

. is community property and what

is separate property cannot be changed by statute.

Under the old statute, community property was defined as "all property

acquired by either the husband or wife during marriage, e:x cept that which is

the separate property of either, ,,5

and under another article of the same

statute , the wife's separate property was defined as "all property of the wife,

both real and personal, owned or claimed by her before marriage, and that

acquired afterward by gift, devise, or descent •••• ,,6

Under these definitions two questions arise: (1) When do community property laws attach?;

(2) At what time is property character-

ized as separate or community? It is now a well settled rule of Texas

community property law that

, ~he

character of property is determined at

the ,time of its acquisition, 7 a'nd property has been held to be acquired

"as of the time the ownership thereof or claim thereto hcid its inception. ,,8

Therefore, .if real property were bought with community

funds~

the property

I

would be characterized as of the qrne it' was acquired, which would be the

time when the community first had title to 'it, and since it was bought with

community funds, it would be community properW, no matter what funds

were used to payoff the indebtedness created by the purchase of the property. If separate funds .were used to payoff

the indebtedness,

this

,

.

would only affect the right to reimburs'ement.'

In a military retirement benefit setting, since the serviceman is not

entitled to elect to receive the benefits until he has served twenty years

in the service, 9 it is at the end of that.. twenty years that the serviceman

acquires the property.

When examining the inception-of-tltle rule a careful examination

of the different ways the rule is applied is n'e cessary to understand it

'fully, especially as it relates to retirement benefits . In the ,characterization process property has sometimes beet:! said to have its inception

.

10

when a person has an enforceable right to it.

This theory is usually

utilized in cases other than those involving retirement benefits. It does,

- 2-

however, serve as a good explanation for one of the ways the inceptionof-title rule is applied to retirement benefits.

.

,

.

For example, if the husband gets retirement benefits from the Armed

Forces after having served tw,enty years ', the benefits are characterized as

separate or community at the tiine when .they, had their inception, or when

the husband had an enforceable right to them.

Using this analysis, it is

clear that t)1e property is characterized when he is eligible to

.~eceive

the

f

benefits at the end of twenty years , :and not when he entered the

service ',

,

because he had no enforceable right to the. property until he completed

his twenty years of service.

,

Carried a step furtper, if the husband is

'

married at the time the retirement period· is met, all the benefits will be

characterized as community property, and if he 1s not married at the time

~

"

.

the retirement period is met, all the benefits -will be characterized as his

separate property.

This 1s the pure inception-of-title rule.

11

A second application of the rule involves the theory that the compensation accrues to thEj'

, serviceman at ,the end of each year of service.

Even though it cannot be paid until the end of the retirement period, it is

still treated as earned at the end of each ' year, and a completely different

characterization results.

For example, if thll husband is: single during his

first three years of service, then married for the next fifteen years, and

is then single again for the last two years, the retirement benefit, accessible at the end of twenty years, is three-fourths community property and

.

.

one fourths separate property. ,This is the deferred compensation theory.

12

Still another approach is to use the pure inception-of-title rule

to ,see if any of the benefits are community property, and then use the

. ,

deferred compensation theory to determine the exact quantity. This' is

the mixed theory. 13

A recent Texas case involving one of these methods of character14

'

.

ization is Kirkham v. Kirkham.

.In that case the husband was single

for the first, 10 years of his military service, and was married ..for the

next 12 1/2 years, after which he

~as d~vorced. 15 In the qivorce suit,

the trial court awarde'd the wife 30 % of the. husband's retirement pay, and

on appeal, . the husband assigned this as error. ,He contended that his

wife was only entitled to 27.. 8% when properly calculated. Taking a

'closer look at the facts', \ he method of cal<?ulat~on becomes ~vident.

The husband had been buHding his retirement' pay account for 22 1/2

years, 12 1/2 during which he 'w as married. Apparently using the mixed

theory, the court found, first, through the use of the pure inception-oftitle doctrine that there ,}'las community property

involved, since the hus.

band was married when his required time of service had ended. The court

said, "the retirement pay account is an earned property right which ac.

,

crues by reason of his yearS'in the military service, ,,16 and then pOinted

out that the husband's earnings during marriage are community property .

Under the deferred compensation theory, the quantity of community property out of the whole was the proportion of 12 1/2 years to 22 1/2 years

or 55.6%. Half of this amount belonged to each spouse--27. 8%. As

justification for granting 30% to the wife instead of 27.8%, the court of

- 4-

civil appears reminded the parties of the wide discretion vested in the

trial court in partition of community property on divorce.

A related case is Mora v. Mora, 17 in which 'the hus'bahd served

. 25 years and 8 months in the. Marine Corps, including 14 years and 8

months while he was married. The trial court did not find that any of

the husband' s ~etirement benefits were comrounity property, and the

wife complained, on appeal, of this finping.

At the time of the trial

.

"

the husband has not yet retired, . and contended that the court could

not divide the benefits on divorce while he had not received them and

while they were subject to . forfeiture if .he received

a dishonorable

dis'

.

charge while still in the service.

The court rejected this argument,

saying that since he ha's :;erved a sufficient length of time in the service to entitle him to the 1retirement benefits, it was a vested property

right, even though it was not paY<;lble at -the time of the divorce.

There-

fore, it would seem the court was saying that the mere fact the husband

had reached the point where

.he could

elect to receive the benefits, that

!

.

.

the benefits were vested in him at that time.

The court also suggested

that the husband could pay the wife her portion of the benefits if, as,

and when he received them.~8

In suggesting a method of computation on remand, the same court

that had decided Kirkham eight years earlier, used the mixed theory.

Having decided that there was community property involved, they next

implied that the extent of that community property should be determined

- 5 -

by calculating the number of years of service' during whIch the husband

and wife were married, a nd awarding one-half of that proportionate

,

value to the wife. The court was quick to point out, as it did in Kirkham,

that the trial court would not ,have to follow this' kind of equal division on

divorce, considering the trial court's wide discretion in such cases.

Herring v. Blakeley

19

was a Texas supreme court case which in-

volved, rather than military retirement l5enefits, a pension and profitsharing plan and an annuity plan. ,The husband had qualified under both

plans while married and had contributed to the annuity plan with community

funds. At the divorce suit ., the husband listed the plans -as assets in' his

inventory. After the divorce, he changed the benefiCiary on the plans

,

,

'

from his wife to Blakeley I , as trustee, for the' benefit of his minor children.

,

•

I

•

~

He then died and Blakeley brougJ:lt suit seeking a declaratory judgment to

determine whether the plans were 'property, and if so, whether they were

community property.

The Supreme CourJi' held that they '('Tere property and were community

property because 10% vested at the close of each year of employment, and

was, therefore, deferred compensation, haVing its inception at the time it

vested. The contention that'the divorce court could not divide property

which was not available at that time to the husband was struck down by

the court for the reason that community property need not be reduced to

immediate possession before a divorce court can make a division it deems

just' and right. Herring was cited in Mora, probably to refer to this

- 6-,

particular holding.

A more recent case upholding the rule set forth in Herring and

Mora was Webster v. Webster. 20

It added little reasoning to the ·

rule, merely citing Mora as controlling:

--

The case was, however,

!

another example of the court using the deferred compensation theory.

The husband, at the time of the divorce ,had been in the: Air Force

for over 24 ,years and had been married for over 20 years of

th~t

,

period. The computation by the ·appellate

court resulted in a, com,

munity interest of 20/24ths, leading to the assumption that the court

gave to the community only that portion of the eptire benefit, in terms

of years, that the parties were married • .

.

,

,

Prior to 1970, the qupreme Court of Texas had never heard a

case considering the

pro~lem

of characterization of military retire-

·21

ment benefits. It was in Busby v. Busby

first confrontation with the problem.

that the court had its

Major Busby was a member of

the Air Force from 1942 to 1963, and was married to respondent, his ·

.

~•

I

. wife, from 1946 to 1963. The wife brought suit for divorce and acquired a judgment on June 25, 1963, the 'd ecree failing to include any

division or mention of the husband's retirement benefits.: On the same

day that the divorce judgment was granted, the Air Force forcibly retired Major Busby because of a physical disability. In 1967 Mrs. Busby

filed suite for an equal partition of the disability retirement benefits.

The trial court entered a judgment that the wife take nothing, but the

- 7 .-

Texas court of civil appeals reversed, holding that the retirement

benefits were all community property, and the wife was entitled to

one.,.half of them.

On appeal to the Texas Supreme Court, Major Busby first contended that the retirement benefits were separate property, because

he never had a ,property right in the disabilit-y retirement benefits during

marriag~

and, in the alternative, 1£ he did have a propertY.Fight,

,

it arose prior to their marriage, when

he' first became a member

of the

,

,

Air Force.

The court 'rejected these contentions citing Kirkham and

Mora ·for the rule that the military retirement bel)efits we(e earned property rights at the time he was eligible to receive them.

Major Busby then' argued that Mora and Kirkham were distinguishable on the grouni:ls that they dealt with voluntary retirement

benefits and not disability retirement benefits which were involved in

his case. In his brief to the Texas Supreme Court,

22

Busby pOinted

out that under voluntary,,retirement .benefits,

such as those

involved

,

.

in Kirkham and Mora,

the applicable federal statute provided:

Section 8911. Twenty years or more,:

regular or retierve commissioned officer.

The Secretary of the Air Force may,

upon the officer's request, retire a regular or reserve commissioned officer of

the Air Force who has at least 20 years

of service computed under Section 8926

of this title, at least 10 ' years of which

have been active service as a commissioned officer. 23

- 8 - '

Under this statute, Busby argued, the Secre'tary of the Air Force

has the authority, upon the request of the officer, to retire the officer,

but he has no affirmative duty to do so. Therefore, says Busby, the '

Secretary may never retire th7 officer, which cannot make the benefit

vested. The court, in rejecting . this cla.im, pointed out that the federal

statute, as discus sed in the Kirkham and M<3ra cases, were construed

as giving a , vested property right to the iserviceman to the exte.pt that

he became eligible to retire during,:the t~me of the marriage" subjec~

only to his (the serviceman's) election.

The Major then contended that the applicable statute involved

. in this case, Title 10, Unitj;ld States Code, Section 1201,

24

giving

the Secretary of the Air 'Fqrce the authority to retire an officer if the

Secretary determined that' several combinations of contingencies relating to disabilities have been met, also gives the Secretary complete

discretion in deciding whether to retire the serviceman, even if he determines that the servicem~n has met ·the qisability contingencies set forth

in the statute.

Major Busby also tried to point out that there was a dif- '

ference between the disability retirement statute and the voluntary retirement statute, in that one' is a forced retitement statute and the other

allows the serviceman to request to be retired.

The court ambiguously

stated, "the rule applied in the voluntary retirement cases should be

. 'applied here, ,,25 , and that the ' disability retirement benefits 'w ere

community property since they accrued during marriage. ,

In his last argument, Major Busby tried to convince the court that

the suit for partition was barred by res judicata, since Mrs. Busby {ailed

to ask for partition in the diy.orce suit. Although Justice Walker, in his

dissent, agreed with the res judicata argument, the majority did not.

They held that When the divorce court does not divide community property,

the husband and wife become tenants in co'mmon or joint ownefS of the property, and may later sue in partition fOr its division.

It is difficult to ascertai!1 exactly what effect Busby will have on

later cases in the community property-retirement benefits area, partly because so much of trying to gain an understanding of the case must come

•

from implication, and partly because

of the difference in the case's

fact

,

,

,

.

'

situation from those it cited as authority. The court probably used the pure

inception-of-title doctrine, because it held that the right vested in Busby

at the end of twEnty years, "and therefore, all the benefits were community

,.-.or .

property. This result is ' reached even tRough t)1e serviceman was married

during his first four years in the military, yet the case cites as controlling

two cases which used the mixed method.

If the case is construea as actually adopting the

title doctrine, some inequities may follow.

p~re inception-of-

For example, if the husband is

in the service for 19 years, while single, and m,a rried that last year before

retirement, and if, he divorces thereafter, the court will, under this doctrine, determine that all his beriefits are community property, even though

- 10 -

his wife contributed to the community for only one' year. 26 This example is the extreme. but even if the example were stated in lesser

,

degrees. such as the situation in which the serviceman was single '

for only 5 or 6 years out of th,e 20. it would still seem inequitable to

';

allow the wife to receive half

of. all

the . retirement benefits unless she

had spent the entire 20 years contributing to' the community.

If the case is construed as adopting the mixed rule. the }nequi"

r

ties in the preceding hypothetical ~re resolved. since under ,this rule.

if. at the end of 20 years • .the serviceman ·is married. the court will

decide that community property is involved. but, in calculating just how

much. the colirt will decide that of the total (20/20) the community

gets 1/20 and the sepa~al;.e estate gets 19/20. thus rewarding the community for only that portion duri~g wht'ch a community existed.

Even the mixed rule would result in inequities if the facts were

changed so that the serviceman was married for 19 years of his military

career and then divorced

Even if the court were to-de. on the 19th year.

,

cide that it could divide property that the husband was not eligible to

receive. at the retirement time the court would characterize all the properatyas separate. because the husband wa's not married to this particular spouse at that time.

27

The inequities involved in this example

are more limited. since the less the time the wife is married to the serviceman the less deserving she would be of a share in the benefits .

-

-11-

Probably the most equitable method of chara'c terization is achieved

through the use of the deferred compensation rule.

Under this rule, at

,

,

least. the wife.is given a one-half share in that portion of retirement

benefits which accrued while , she was contributing to the community effort. 28

As to the ambiguity in the court's treatment of the two different types

of retirement statutes, the court seems to be correct in holding that the disability retix:ement benefits were commun1ty property, because they apparently

,

did accrue during the time while ' the

Secretary did

, parties were married; the

'

determine that Major Busby was disabled on the same day the divorce judgment was entered and did actually retire him.

H;owever, .the court, in stat-

ing that retirement benefits are vested on the day that the serviceman has

-

,

,

completed his required number of years. subject only to his (the serviceman's) election, fails to properly cons't rue the meaning of the word "may"

in, the so-called voluntary statute,. According to the way the statute is

drafted. just because a serviceman has been in the service for 20 years

and requests the Secret<;"ry of the Air FOI;,ce to retire him so that he may re-

ceive his benefits. does not mean that the Secretary must' retire him. 29

Use of the word "may" confers only the a'u thority and not a duty upon the

Secretary to act.

30

.

'

,

Therefore. it is difficult to reconcile the court's hold-

ing with a careful analysis of this statute. As for the disability retirement

statute. the court does no more than restate its provisions through examples.

and leaves subject to interpretation the question of how it will be applied if

the Secretary has not determined that the serviceman is disabled at the time

- 12 -

of the divorce (assuming also that he is even under a duty to retire the officer if he finds him disabled).

,

At first glance, the case seems to be contradictory, in that it impliedly uses the pure inception-of-title 'rule while apparently relying on

.'

authority which uses the mixed ·rule. Tne court may have been trying to

give a reason for this anomaly by stating, "We strongly suspect that the

trial court which

pronounced the decree 'of divorce and ordered..a division

,

of the estate of the parties in 1963,; would not have divided

~efendant's

disability retirement benefits as is being accomplished here. ,,31

The implication of this statement seems to, be, as the court mentioned

earlier in its opinion, ' that when the divorce court does not, in its decree,

divide part of the commllllfty property, the htisband wife become tenants-incommon of that communit1 property. When a 'suit is brought to partition that

kind of property, the court is allowed only to decide if the property, as a

whole, is community or separate, and may not, as in an original suite for

divorce, exercise discre,tion

-in dividing the property "in a manner that the

.

~

court deems just and right, having due regard for the rights of each party

and any children of the marriage. "

32

If the court determines that the property

is c'o mmunity, then the property belongs to the husband and wife in equal

parts.

33

.

Therefore, the Supreme Court in Busby was without power to deter-

mine anything except whether the retirement benefits were community or

separate property, and having determined that they were community property,

it was without power to further determine the extent of that community property.

- 13 -

Assuming this implication to be correct, the effect of Busby is

markedly narrowed to cases involving suits · for partition after the

,

.

divorce court has not settled the spouses' rights in the property,

and future cases which do not

, include the same ' situation, . will probably be decided according to Mora or Kirkham.

Even without assuming the .implication to be correct, Busby

leaves the , problems of interpretation of the statutes and

exac,~ly

how

to determine

'character of the benefits

unre. the separate or commimity

.

..

. solved. In short, Busbyg.1ves little direotion or finality to the application of the inception-of. title rule to, retiremel)t benefits.

- 14.

,

Footnotes

1.

Rompel v. United States. 59 F. Supp. 483. revd. on' other

grounds. 326 U.S. 367. 694 L.Ed. 137. 66 S.Ct. 191 reh. den ••

Sandoval v. Priest. 210 F. 814.

2.

Tex. ,Const. art. VII. § 19 (1845)~ 2·Gamme1 • .Laws of .

Texas. 1293.

3.

Tex. Const. art. XVI § 15.

4.

114 Tex. 535. 273 S. W. 799 (1925).

5.

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann. art. 4619. The present statutory

definition may be found in,"Tex • .:am. Code Ann . tit. 1.. § 5.(11- (1970).

6.

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat; Ann.

--- =---- =-=-- -=-- =--

art. 4614. A similar definition

of the husband's separate property is found in Tex. Rev. Civ . Stat. Ann.

art. 4613.

7.

Smithv. Buss. 135 Tex. 566 . ~44 S.W.2d 529 (1940).

8.

Lee v. Lee. 112 Tex. 392. 247 S.W. 828 (1923).

9.

An officer may request to be retired after twenty years of

service. 10 U. S.G.A. § 8911 (1970).

- 15 -

10.

Strongv. Garrett, 148 Tex. 265, 224 S.W.2d 471 (1949),

Bishopv. Williams, 223 S.W. 512 (Tex. Civ. App.--Austin 1920,

writ refused); Creamerv. Briscoe, 101 Tex. 490. 109 S.W " 911

(1908) •

11.

See Note. Military Retirement Benefits As Community

Property--Busby v; Busby. 25 Sw.

-

" 12.

L.r.

-....,.

340. 342 (1971).

Id. at 343.

13.

Id.

14.

334 S.W.Zd 393 (Texas. Civ. App.--SanAntonio 1960,

no writ).

15.

In Note. Military Ret"irement " Benefits As Community

Property--Busby v. Busby. 25 Sw.

-

L.r.

--

340. 343 (1971), the author

is somewhat confused as to "the fact situation in Kirkham, in that

h~

points out that the serviceman was married after twelve years in the

service.

16 .

Supra note 14 at' 394.

17.

429 S.W .2d 660 (Tex. Civ. App.--San Antonio 1968, error

dismissed, w.o.j.); noted in 22 Sw.

- 16 -

I:..r.

888 (1969).

18.

Hughes, Community Property Aspects of Profit-Sharing and

Pension Plans--Recent Developments and Proposed Guidelines for the

Future, 44 Texas. L. Rev. 86.0, 869 (1956).

--

--

19.

385 S.W.2d 843 (19,65), noted in 19 Sw. L.l. 37.0.

2.0.

442 ' ,S. W • 2d 786 (Tex. Civ. App.::"-San Antonio 1969, no writ) •

21.

457 S.W .2d 551 (197.0).:

22.

Brief for appellant at 457 S.W. '2d 551 (197.0).

23.

1.0 U.S.C.A.

fj

8911.

,

24.

" ••• the Secretary may retire the member, ••• if he .deterI

.

'

•

•

miries ......

25.

Supra note 21 at 554.

26.

Supra note 11 at 343.

27.

Supra note 11 at 348.

28 .

Johnson--Retirement

Berlefits As Community Property in

(

,

Divorce Cases, 15 Bay. L. Rev. 284; 289 (1963).

29.

cf; Love v. Dallas, 12.0 Tex. 351, ,4.0 S.W.2d 2.0 (1931).

- 17 -

30.

If mere election to retire would have been intended to be

the meaning of the statute, it should have been drafted in the followinq form: If the officer req,uests , ••• the Secretary of the Air Force

shall retire the officer.

31.

Supra note 21 at 555.

32. , Tex. Fam. Code Ann. tit. 1', § ' 3.63 (1970).

,

33.

Kellerv. Keller, 135 Tex. 260, 141 S.W.2d 308 (1940).

- 18 -