under siege Life for Low-Income Latinos in the South

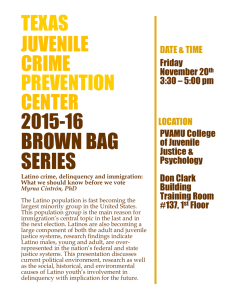

advertisement