Document 13037991

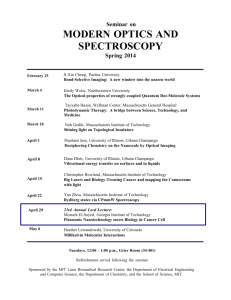

advertisement