LOtC Consultation:

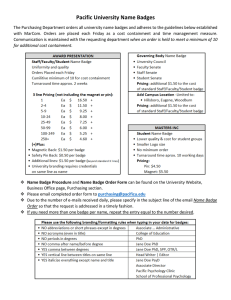

advertisement