School of Slavonic and East European Studies Alumni Stories

advertisement

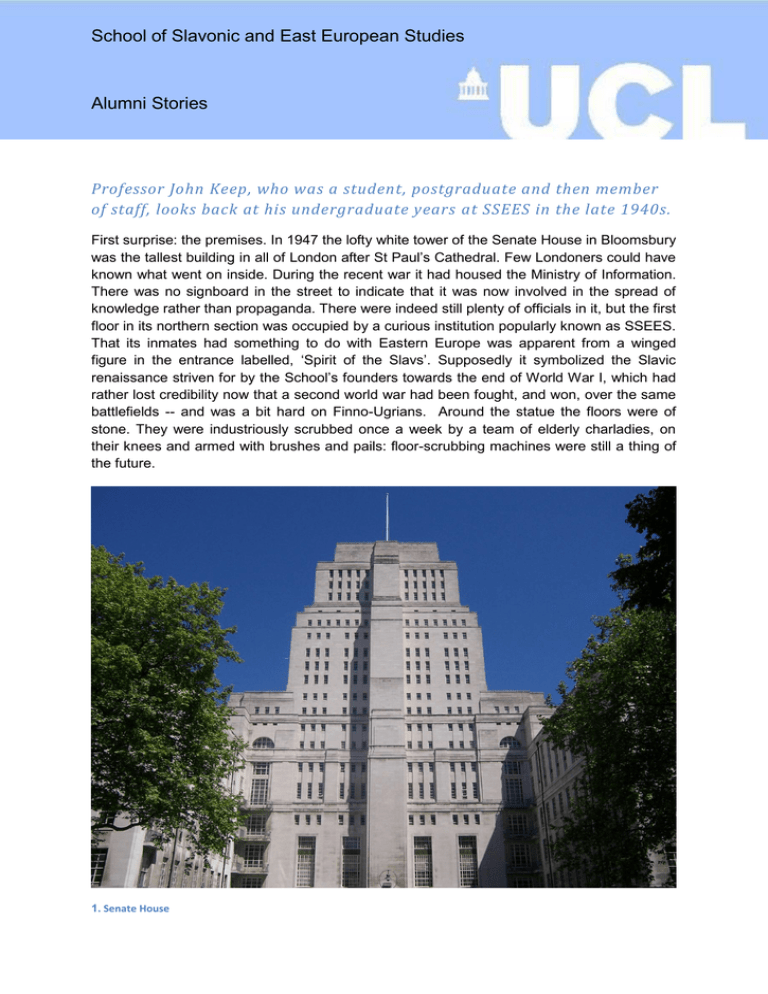

School of Slavonic and East European Studies Alumni Stories Professor John Keep, who was a student, postgraduate and then member of staff, looks back at his undergraduate years at SSEES in the late 1940s. First surprise: the premises. In 1947 the lofty white tower of the Senate House in Bloomsbury was the tallest building in all of London after St Paul’s Cathedral. Few Londoners could have known what went on inside. During the recent war it had housed the Ministry of Information. There was no signboard in the street to indicate that it was now involved in the spread of knowledge rather than propaganda. There were indeed still plenty of officials in it, but the first floor in its northern section was occupied by a curious institution popularly known as SSEES. That its inmates had something to do with Eastern Europe was apparent from a winged figure in the entrance labelled, ‘Spirit of the Slavs’. Supposedly it symbolized the Slavic renaissance striven for by the School’s founders towards the end of World War I, which had rather lost credibility now that a second world war had been fought, and won, over the same battlefields -- and was a bit hard on Finno-Ugrians. Around the statue the floors were of stone. They were industriously scrubbed once a week by a team of elderly charladies, on their knees and armed with brushes and pails: floor-scrubbing machines were still a thing of the future. 1. Senate House But who had really won the war? The grim figure of Joseph Stalin loomed over the region and the ‘cult of personality’ was in full flower. The leading light among the historians was the idealistic Reginald Betts, an acclaimed authority on Jan Hus and the medieval Czechs. Czechoslovakia, he thought, might with luck still form a bridge over the rapidly forming gulf between East and West. But the latest defenestration of Prague (Jan Masaryk, from a window of the Czernin Palace) made it clear that this was an illusory hope, and thereafter disappointment was written all over the humane teacher‘s features. He continued to queue up for morning coffee (served inappropriately in the Masaryk Hall) with the students learning Hungarian. R. R. Betts was an exception in socializing with undergraduates. The rest of the staff were distant figures. The formidable Dorothy Galton slotted one into the approved notch in the academic structure. She was actually an expert on bees, as it turned out, a skill no doubt suited to her dealings with students. The School was still young and there were as yet no departments, yet departmentalism was writ large. Most students did ‘the language and literature’ of one or other of the east European peoples, under the supervision of the redoubtable Professor Matthews, who hailed from the Baltic and was reputed to speak no less than 23 languages. Russian was acknowledged by His Majesty’s Treasury, no less, as an ‘exotic’ language that entitled some of its devotees to modest financial support: enough to keep one alive (lunch in the Senate House cafeteria cost 2 shillings), but not to patronize London Transport (one could buy a bike and so save sixpence on the fare to Golders Green), let alone restaurants, the theatre, or other cultural delights. Sporting facilities were indeed provided, but in inaccessible Fulham. A room could be rented for £2.10s (that is, two and a half pounds) a month, and Dorothy Galton kept a list of landladies, whose doings would doubtless deserve separate treatment. Aficionados of history (for that was what the Russian Regional Studies course turned out to be about) first encountered the memorable Bertha Malnick, whose colourful style of dress and coiffure was a healthy antidote to the unfathomable doings of the Kievan Rus‘ princes. Unfathomable because there was as yet no suitable textbook of Russian history in English: (Sir) Bernard Pares did not get one very far, and the vast literature in Russian was inaccessible due to our ignorance. True, Anna Pankratova’s work had indeed been translated, but more valuable was the work of the Soviet economic historian Peter Liashchenko, since the emphasis in teaching was heavily on the economic and social aspects, viewed as more ‘progressive’. This suited us fine since we were all politically on the left, many even far left (except for the lone Conservative, who went off to take over his Papa’s wine business, leaving us to cope as best we could with the plight of various categories of serf). One or two colleagues were actually competent in the refinements of Marxism. They relished the informal (and probably illegal) seminar on the topic offered to volunteers after regular teaching hours by the amiable Doreen Warriner, who was actually no dogmatist but a valued expert on social matters who later worked for the UN. A few of us dared to put socialist principles into practice, for instance by backing striking workers at the Savoy Hotel. The man who knew all about the class struggle was the formidable Andrew Rothstein, whose father had once been close to leading Bolsheviks. He was well liked and an excellent teacher, but these gifts did not help him when political storm clouds began to gather over his head; fortunately for him, after the celebrated ‘Rothstein Affair’ (which brought the School a good deal of adverse publicity), he returned to left-wing journalism and so his sufferings were not too severe. Over all these shenanigans presided the somewhat mysterious George Bolsover. Why the place needed a Director was (and perhaps still is) a puzzle. George was in reality a stalwart, good-natured and even tolerant, generous man, but he was not prodigal with public funds (one of his maxims was that a librarian should not be paid a salary running into four figures) and at the time he was feared and privately mocked - treatment that in retrospect one feels he did not deserve. As for the library, whose riches one could scarcely skim, access was governed by the lively and somewhat eccentric Arthur Helliwell. In summer he would go cycling through northern France. This was about as far as anyone then thought of venturing - certainly not behind the Iron Curtain, still opaque. In any case foreign travel was difficult: there was an official allowance, sometimes as low as £25 per annum, and its issue was firmly marked in one’s passport. But who were we to question the doings of our wise, paternalistic Labour government? Was it not dedicated to the task of making Britain the best country in the world to live in, marked by social equality, free health provision, and other noble virtues? Food ration cards were honoured, and occasionally items such as cheese would come off it. Anyway, we were certainly better off than those wretched Russian serfs one heard so much about. 2. Professor John Keep By Professor John Keep