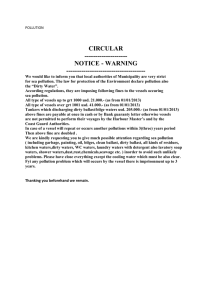

FEDERAL WATER POLLUTION CONTROL ACT

advertisement

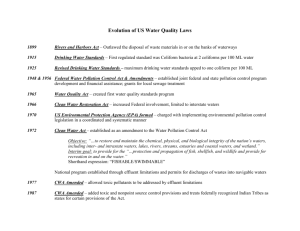

FEDERAL WATER POLLUTION CONTROL ACT AMENDMENTS OF 1972 CECIL C. KUHNE Table of Contents Introduction I. Water Pollution: An Overview A. Economic Considerations B. Water Quality Standards and Effluent Standards C . Biological .Considerations D. Enforcing Standards II. Legislative Approaches A. Prior to 1972 Amendments B. 1972 Amendments III. Effluent Standards A. Technological Availability and Economic Capability 1. Technological Availability 2. Economic Capability B. Conflict Between Effluent and Water Quality Standards C. No D~scharge Policy IV. Permit System A. Defining "Navigability" B. Navigability and the Commerce Clause C. Enforcement D. Federal-State V. Recommendations Conclusion ~elations Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 Introduction Water pollution is one aspect of environmental degradation which is of particular concern to society because it has resulted in rivers and lakes that can no longer support fish and plant life, unsafe drinking water, and destruction of other natural resources. Meanwhile, the demands for water resources from a growing population and industry have increased at unanticipated levels, and yet water purification technology has not received adequate funding from the private and public sectors. Congress, in the 1972 Amendments of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act,l has made some sweeping declarations of policy which indicate that its perception of the water pollution problem has broadened considerably from earlier , legislative acts. The Act specifically recognizes the danger of toxic pollutants 2 and establishes the regulatory machinery to prevent discharges to the nation's waters. 3 And for the first time, the Act addresses the non-point source problem. 4 The 1972 legislation reflects both a desire for rapid improvement in the quality of the nation's waters and growing concern over the high cost of achieving such improvement. Prior federal water pollution laws had not done much to reduce water pollution; provided such an overhaul. ~Vhile the 1972 Amendments earlier federal legislation -2- followed the approach that certain waters could remain severely degraded to permit industrial and other uses, the 1972 Amendments rejected this concept and adopted instead the view, well stated in the Senate Report, that "no one has the right to pollute - that pollution continues because of technological limits, not because of any inherent right to use the nation's waterways for the purpose of disposing of wastes. liS The new law left behind the idea of relying upon the assimilative capacity of waterways and made it clear that streams and lakes are no longer to be considered part of the waste treatment process. In implementing these new principles, however, the Act recognized and dealt with economic and technological constraints. The regulatory program that resulted was strong but practical. I. water Pollution: An Overview A. Economic Nature of the ~roblem As society grows, the volume of wastes to be assimilated increases, and the quality of water diminishes as a result. Until recently, these water resources have been regarded as free goods and have thus been used carelessly. Water pollution arises in large part because industry is not charged with the costs which its wastes impose on society. Rather, these costs are passed on to the downstream users of the river in the form of lower quality water, higher treatment costs, or beneficial uses foregone. The ability of an industry to pass the costs of its actions to others results in an external -3- " 6 d lseconomy. Aside from the pressures of public opinion, industry has no economic incentive to minimize the costs of pollution, while it must attempt to minimize its costs of production. Furthermore, investment in pollution abatement methods does not generate any corresponding revenue; it only entails costs. Consequently, in order for pollution control to be accomplished, " 7 the missing economic, or other incentives, must be provided. Since industry has, until recently, managed to escape the costs of pollution abatement, the prices of industrial products have been lower because these prices did not include the costs of reducing or modifying the waste products generated. As a result, our standards of living have improved in terms of relatively cheap and mass-produced goods but have deteriorated through an increasingly polluted environment. Consumers will ultimately have to pay the costs of improved water quality, which necessarily requires that industrial output and community services will become more expensive as they are held accountable for costs of water pollution. 8 B. water Quality Standards and Effluent Standards There are basically two administrative approaches to water quality control -- the water quality standards approach and the effluent standards approach. Water quality standards specify the maximum amounts and concentration of various pollutants which can be present in a waterbody at any given time so that the waterbody may remain compatible with its designated use. These standard"s are concerned with the resulting quality of the water and not upon >the - level of -4- pollutants being discharged by ' an individual firm. Effluent standards, however, limit the absolute quantity of particular pollutants which may be discharged by individual sources into the water and are not dependent upon the resulting quality of the waterway. Historically, the implicit legal definition of water pollution has been "any condition which interferes with the desired use of a waterway." A body of water was regarded as polluted if society could not use it for a desired purpose. In keeping with the "desired use" concept, federal water pollution control law prior to 1972 was based upon stream-use classifications and water quality standards. States were first urged and later required to classify interstate and then navigable waters in categories extending from class A (swimming) down to class D (agricultural and industrial use) . Once stream-use classifications had been established, a state was to apply water quality standards to each waterway according to its'designated use. In theory at least, states were then to convert water quality standards into effluent limitations, utilizing water quality standards, water quality modeling, and wasteload allocations. 9 The liabilities of the "desired use" concept, along with stream-use classifications , and water quality standards, soon became apparent. State agencies, often influenced by industry, set classifications and standards at low levels in some cases even lower than current conditions and in others at levels which would have significantly degraded relatively pure waters. If stricter laws were passed, -5- industry simply threatened to move to another iocality or state where laws were more lenient towards the disposal of industrial wastes. lO Furthermore, in most cases water quality standards are unenforceable, and unless the water quality standards are directly associated to effluent limitations, these standards cannot be converted into effluent limitations for specific dischargers without sophisticated load allocations; These load allocations require a consideration of hydrological, biological, and other factors which determine the assimilative capacity of a waterway.ll As a result, prior to 1972 most states did not even attempt to set effluent limitations, and state enforcement procedures were only initiated in cases where discharges , lowere d t h e qua I lty of water below the water qua l'lty standar d s. 12 C. Biological Considerations Some programs of water quality control are also dependent upon a:knowledge of the biological characteristics of pollution. The capacity of a stream to assimilate a waste is determined by the properties of both :. the stream and the waste. The degree of dilution of waste discharge is generally related to the volume of water in the stream and the capabilities of the waste to dilute. This dilution, in turn, is dependent on the chemistry of both the pollutant and the stream. Specifically, the more dissolved oxygen there is in the stream, the greater will be its assimilative capacities. 13 In order to convert water quality standards into effluent standards, wasteload allocations must be determined. -6- Wasteload allocations must then - be developed from water quality models which reflect the condition of the waterway, its assimilative characteristics, and the potential effects of discharges on it. But water quality modeling is still an inexact procedure, especially with regard to discharged - substances other than biological oxygen demand (BOD) or un suspended solids. Furthermore, assimilative capacities of even individual waterways are variable, depending on factors - -. h d 14 suc as vo ume,I temperature, an tur b 1- d lty. D. Enforcing Standards Once effluent limitations are set, the enforcement of those standards is relatively simple. Monitoring devices installed by the company measure the amount of pollutants emitted into the waterbody. water quality standards, however, are less susceptibie _ to accurate enforcement. These standards are based upon the desired use , concept and the reSUlting condition of the water, not the exact amount of pollutants discharged by any particular industry. Thus, the standards, by their nature of measurement, are inexact. The discharger then is unable to know at any specific time whether his level of discharge will violate water quality standards. And, in the situation where there are a number of industries discharging into a body of water, it may be impc~sible to determine which industry reduced the quality of the water below a specified standard. Water quality may also be influenced by a company's location on a stream, with lower water quality accumulating downstream; the downstream users are then required to meet stricter standardE -7- for their emissions in order to meet the same water quality standards. It is clear, then, that water quality standards without effluent limitations are valueless for enforcement purposes except in unusual cases of gross violations, such as Spl'II s. 15 II. Legislative Approaches A. Prior to the 1972 Amendments Governmental regulation of environmental conditions for the public good has been accepted as a proper exercise of governmental regulatory authority. The beginning of governmental efforts to control water pollution commenced with the formation of the Committee on Public Works of the House of Representatives under the Reorganization Act of 1946. 16 Prior to 1946, legislation for clean water was included in the Oil Pollution Act of 1924,17 the Public Health Service Act -" of 1912,18 and the Refuse Act of 1899. 19 The Federal Water Pollution Control Act was initially 20 -21 enacted in 1948 on a temporary basis and extended in 1952. The 1948 Act recognized the primary rights and responsibilities of the state to control water pollution, a congressional policy which is still reflected in the present law. The initial act provided for comprehensive water pollution control programs, research, and financial assistance to states, municipalities, and interstate agencies for waste treatment f aCl'1"ltles. 22 Also included was a program for construction loans and preliminary planning grants that were never implemented because funds ~~ never appropriated. 23 The -8- pollution of interstate waters ·which endangered the health or welfare of persons in a state other than that in which the discharge originated was declared to be a public . nuisance, subject to abatement. 24 Abatement procedures provided for federal court suits after two notifications were given to the discharger and the state in which the discharge occurred. 25 If no remedial action was taken.by the discharger or the state, the Act required that a public hearing be held. Only after the discharger was given a "reasonable" opportunity to comply with the recommendations resulting from the hearing could suit be filed. In addition, the Act required that the state in which the discharge originated consent to the suit. Amendments passed in 1956 26 auth9rized federal grants for construction of waste treatment works, as well as for establishment and maintenance of state water pollution . control programs. 27 These firnendments also established a three-step enforcement procedure applicable to interstate pollution of interstate waters endangering the health or welfare of persons. 28 The first step involved a federal-state enforcement conference, with participation by local officials and other interested persons; to discuss the pollution problem. If the conference was not successful, a public hearing followed. The conference would be called either at state request where interstate or intrastate pollution was involved, or initiated by the federal government where interstate pollution was concerned. The conferees convened to review the existing situation and any progress made, to -9- lay a basis for future action, .and to give states, local governments, and industries an opportunity to take any appropriate remedial action pursuant to state or local law. In 1961 enforcement authority was extended to navigable waters, as well as interstate waters, and was applied in cases of intrastate pollution on request of the governor of a state. 29 The term "interstate waters" was redefined to include coastal waters. These changes greatly expanded the subject matter jurisdiction of the law. In addition, the authorization for grants, both for construction of waste treatment works and for state water pollution control programs, was increased and extended. The 1965 law provided for the establishment, revision, and enforcement of water quality standards for the nation's waters. 30 This legislation represented ·a new approach to water pollution control. The public nuisance concept of "'-, prior legislation was abandoned. The standards consisting of water quality . criteria were designed to provide water of proper quality for a range of designated uses. A plan for implementation and enforcement was to be prepared in conjunction with the standards. The states were given the first opportunity to adopt standards subject to federal approval, and if a state failed to do so, the federal government set the standards. Any discharge which reduced the quality of the receiving water below the criteria or in violation of any implementation plan was subject to enforcement action. Federal enforcement consisted . of bripgirug -10- suit for abatement after at least ISO violation to the discharger. dax~tice of During the ISO-day period, informal hearings were held to attempt to correct the violation. , Because of the inefficient nature of the ISO-day notice procedure, the 1965 Amendments became deficient as an enforcement act. Enforcement proceedings usually consisted of endless negotiations, which rarely resulted in court , 31 actlon. The Act was again amended in 1966 32 and 1970. 33 The Water Quality . Improvement Act of 1970 provided for the abatement of pollution by oil in the navigable waters of the United States, adjoining shorelines, or contiguous zones. 34 ' d 'ln severa 1 lnstances. ' 35 Fe d era 1 en f orcement was aut h orlze B. 1972 Amendments The Federal Water Pollution Control Act, as amended in 1972, is . divided into five major parts: related works, prog~ams, (1) research and (2) grants for construction of treatment (3) standards and enforcement, licenses 7 and (5) general provisions. (4) permits and Other sections of the amended legislation include provisions for studies of the efficiency of water pollution controls,36 the determination of national policies and goals relating to water purification,37 loans to small business concerns for water pollution control , 3S an d cltlzen ' , ,39 SUltS. f aCl'I'ltles, The primary objective of the 1972 Amendments is stated in the Act - "to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation's water~." Report confirms this objective: The House -11- The word "integrity" as used is intended to convey a concept that refers to a condition in which the natural structure and function of ecosystems is maintained.40 The "natural structure and function of an ecosystem" is, as the House Report notes, relatively well understood by ecologists. The use of this concept gives the Act the · 1 b aS1S. . 41 s t ronges t POSSl. b e l enVlronmenta The most constructive interpretation of the Act seems to regard Congress as adopting legislation which places a heavy burden of persuasion upon those who desire the use of the nation's waters for waste assimilation. 42 Essentially, the 1972 Act calls for the elimination of all pollutant discharges into navigable waters by 1985. 43 By 1983 there is to be achieved a goal of water quality which will provide for the protection and propogation of fish, shellfish, wildlife, and recreation in and on navigable waters. 44 The Act also distinguishes between discharges . ~ from industrial establishments and municipal waste treatment . 45 plants. For the industrial sector, a two-stage cleanup program is required. By July 1, 1977, industrial point source dischargers must -meet a level of effluent reduction capable of achievement by "the best practicable control technology. ,,46 The period from July, 1977, through July 1, 1983,is directed toward the achievement of even higher levels of effluent reduction. By July 1, 1983, industrial users will be obligated to use the "best available control technology" in reducing wastes discharged. 47 Although the Act does not define the terms "best practicable" and "best -12- available," it is clear from the legislative history that the distinction is intended to reflect the need to achieve even higher levels of control during the second stage. 48 For municipal waste discharges, the Act requires secondary treatment by July 1, 1977~9and the application of even more stringent controls by mid-1983. 50 Although the basic requirements of the Act are involved with the establishment of specific effluent limitations, the concep t 0 . . ' d . 51 stream s t an d ar d s '1S re ta1ne f rece1v1ng These stream standards on all navigable waters constitute a floor level of quality. If "best practicable" and "best available" treatment will not meet in-stream standards, higher levels of treatment will be required. 52 The major regulatory device for attaining these levels of control for both industry and municipalities is a national ·of discharge permits patterned after the 1899 Refuse 53 Act permit P!ogram. Permits defining the limits of syst~m discharge are to be issued by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to all water users: municipal, agricultural, and industrial. However, the Administrator of the EPA ist:'.? ~ ~ " ~ :.,'-.:. / authorized to delegate to the states the operation of this program if a state requests this delegation and can meet the 54 55 detailed approval conditions of the Act. Section 1319 is the enforcement provision of the Act; it, unlike prior federal enforcement statutes, is direct and concise. Its primary attention is directed to various effluent limitations established in Title 111. 56 For a violation of either an effluent limitation or a -13- penuit condition, the Administrator is entitled to seek / relief. In order for states to enforce their own pollution control programs, the Administrator may defer action against a polluter for 30 days after he notifies the state of the 57 However, if the state does not act promptly, 58 the Administrator is obligated to seek injunctive relief. violation. wilful or negligent violation of an effluent limitation or permit condition may result in a fine up to $25,000 per day of violation and imprisonment for up to one year. 59 The ·federal enforcement role is intended to be supplementary to the enforcement efforts of the states. However, if a state seeks to administer the permit program, it must have the same enforcement capabilities as those provided in Section 1319 before the delegation will be allowed. 60 The Act also grants financial assistance to municipalities to enable them to achieve the required effluent limitations and other requirements under the statute. 61 Unlike prior " federal legislation, which simply provided construction grant assistance to local governments, the 1972 Act recognizes the public utility aspects of sewage systems through several requirements, and as a condition to the receipt of construction grant funds requires: (1) a mandatory system for planning area-wide" waste water management, 62 (2) service charges with the municipal recovery of federal capital investments made for the treatment of industrial wastes in municipal systems, 6ri.7 and (3) pretreatment of industrial wastes discharged to municipal systems. 64 There are other very important provisions in the Act, -14- but the general framework is designed to give the states .' JII the first opportunity for eforcement. If the state fails to act promptly, federal intervention is a certainty. The Act is written so that a state which fails to adopt a comprehensive planning program will also lose its "rights" under the program granting financial assistance in the construction of municipal waste treatment facilities,66 and will not be eligible to receive delegation of permit authority.67 III. Effluent Standards The 1972 Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments are unique in that the water quality standards they establish are no longer dependent upon the quality of the body of water into which the municipal or industrial waste water is being discharged. Rather, the emphasis is placed on treatment of discharges at specific point sources by the "-. .best available technology. 68 Water quality standards were referred to as "receiving water standards" because they were based upon the resulting quality of the river or lake, and not upon the amount or quality of the waste water being discharged by the polluter. The new standards, however, are known as effluent limitation standards because they are dependent upon the quality of the waste water being discharged, irrespective of the quality of the receiving river or lake. A. Technological Availability and Economic Capability By 1977 industry must meet effluent limitations which can be achieved by application of the "best practicable -15- control technology currently availabl~." By 1983 it must achieve control levels based on the "best available technology economically achievable." Each standard contains two basic elements: a notion of technological availability ("currently available" and "available") and a notion of economic capability ("practicable" and "economically achievable") 1. Technological Availability Water quality can be improved by (l) chang~s in the manufacturing process which will allow the recovery of by-products, along with other waste reduction measures, or by (2) installing treatment devices at the end of the manufacturing process. technology," refers only If the term in the Act, "control to ',~.tr.eatrnerit.; f.a6ii.i·-E ies· at the end of the manufacturing process, effluent limitations will not reflect the maximum possible reductions in waste levels, and water quality improvement will be more expensive. The d~cision 69 by the Administrator concerning treatment technology will probably depend on whether particular: process changes can be widely adopted by an . indus~ry. 70 If manufacturing processes vary widely in an industry, it is unlikely that the Administrator can justify effluent limitations which depend on a particular process change applicable to only a portion of the firms in the industr¥. Because most treatment technology consists of "add-on" devices, it can be applied to a variety of manufacturing processes. Thus, effluent limitations based on treatment technology, as opposed to process changes, will be more uniform. Of course, in the situation where firms in an -16- industry use the same manufact~ring process, standards based / on process changes could produce a comparable degree of ' 71 unl' f ormlty. "unl f ' 72 To th e extent th at t h e Act requlres ormlty, the EPA may be forced tb sacrifice both efficiency and potential improvement in water quality. Another major question concerns the point at which technblogy qualifies as "available." Both the 1977 and 1983 standards stress this concept of availability. Much will depend upon whether technological availability is .measured (1) by the current operational capacity of an industry, (2) by new scientific and technical knowledge already available in the laboratories and design rooms, but not yet generally available in practice, (3) or by the potentialities of new research. 73 The availability is further complicated by the constant development of new water pollution control devices, so that the time fixed for determining when technology is available may be critical. Frequently there is a delay of a year or more between the time when a discharger adopts a control program and when he begins construction. Although it seems logical to determine technological availability at the time effluent limitations are adopted, the Act has been interpreted to require the determination at the time when construction begins. two choices: This would give the Administrator he can impose effluent limitations based on his prediction of what technology will be available when construction commmences, or he can rewrite the requirements should new technology become available before construction -17- starts. If he chooses the first alternative and his judgment proves inaccurate, his action could probably be litigated in court under Section 1369~ If he chooses the second course, the Administrator may have to revise effluent limitations just when the discharger is prepared to install devices designed to meet the original limitations. 74 Despite the importance of technological development, the technology-based regulatory scheme established by the Act provides no incentives for such development. In fact, industry may have a positive incentive not to develop new technology, for once a new process is perfected, it becomes eligible for adoption by the EPA as the "best practicable" or "best available.,,?5 Even though research may lead to development of a new control technology capable of attaining even higher levels of treatment at lower cost, the possibility is not sufficient to overcome -, t he disincentive. Such a control technology; even if developed, would only be applied when bbth the capital and long-term operating costs of the new process are expected to be lower than operating costs of existing control technology. Thus, regardless of how effective a new technology may be, voluntary conversion is unlikely since . . . ' 76 it wlll lncrease net 1 ong-term costs . ln most ln d us trles. 2. Economic Capability There is the fundamental problem of what is meant by the term "economically achievable" or "practicable." Whether applied to a plant or a "class or category" of industry, a standard expressed in terms of what is -18- "economically · achievable"or "practicable" provides no definite restriction to the expenditures which the EPA . f or contro 1 d eVlces. ' 77 can requlre One can imagine several possible interpretations of these two phiases; extending from a standard which allows a fair return on investment to one which leaves the firm at a zero profit level. The question then may be what percentage of the firms in a class or category must be able to afford a particular . control technology before it qualifies as "practicable" or "economically available.,,78 In other words, how many marginal firms can be driven out of business before the standard becomes unacceptable? 79 It has been sugggested that the best practicable control levels be determined on the basis of "an average of the best existing performance of plants of various sizes, ages, and unit processes within each individual category." interpretat_~on This seems to assume that since some firms have been able to afford control equipment, most of the others will be able to afford the same level of control. This assumption is unrealistic, however, since the ability to afford control equipment depends largely on the economic condition of the firm. Less profitable firms and those which are unable to obtain long-term credit may be ' unable to finance control expenditures. Determining economic capability is especially difficult when the average control level is substantially above the level achieved by the best performers in classes which have inefficient technology.80 The Act attempts to solve the economic capability problem -19- by requiring ~ cost-benefit analysis in order to determine what is meant by the term Ubest practicable." Perhaps an even more important question raised by th~ economic capability req~irement is what distinguishes effluent limitations based on the "best practicable control technology" from those based on Ubest available technology economically achievable." The most significant difference in the ueconomically achievable" standard is that only internal costs are considered in the balancing between costs and benefits. Since external costs are no longer considered, the EPA can set an effluent limitation requiring no discharge of pollutants where the requisite technology is available at a r-1~as-dna:hle ::Co-s:t and has been adequately demonstrated if not routinely applied. In other words, the ubest available" technology refers to the best performing company in a particular industrial category, while the Ubest pract-\cable" technology refers to the average of the . most efficient performers. 82 The absence of specific cost-benefit analysis in the Section 1314 (b) (2) (B) guidelines for best available technology suggests that costs should be a restricting factor only when costs are substantially out of proportion to the expected benefits. This interpretation would be consistent with the requirement that the second stage limitations provide "reasonable further progress toward the goal of eliminating the discharge of all pollutants." 83 A number of studies have demonstrated that the cost of treatment tends to rise rapidly once the 90 to 95 per cent -20- treatment level is attained. In some cases this may mean that zero discharge will cost twice as much as treating up to a 90 per cent treatment level. 84 At this level of treatment, a cost-benefit analysis tends to become unreliable. 8S After 1977 the number of firms threatened with closure by enforcement of the "best available" standard could be substantial. While undoubtedly many firms could afford additional expenditures of the magnitudenecessary¥ to eliminate the last five to ten per cent of waste discharge, there may also be a large number of firms unable to defray those expenses. Unless control technology is developed which is capable of achieving a high degree of treatment at relatively low costs, the EPA may find it difficult to enforce the post-1977 standards. 86 A -:change·:in effi.uent ~:; staridards , :.. caused· -PT either technologic~ or economic conditions, also presents problems to industry. An individual company in an industry is encouraged to delay construction ; of sophisticated treatment facilities, due to the failure of the Act to provide sanctions for these industries if the standards are subsequently upgraded. 87 Since . the best economic arrangement of any treatment facility is dependent upon many factors, a change in one of these factors, such as the statutory water quality standards, could make it necessary to improve the facility. This change in standards - would result in a treatment scheme which would not have been selected by that particular industry if their original -21- plan had been based upon the revised standards. A subsequent upgrading of standards would require greater controls before the cost of the treatment systems could be 88 recovered. Other potential problems could arise by a later easing of the 1983 requirements. A lowering of the 1983 standards would make industrial expansion a risky business because one company that builds a new plant could become burdened with the high operating and maintenance costs associated with zero discharge treatment facilities, while a competing plant may incur lower operating costs by postponing construction with the expectation that the EPA will lower the second phase effluent standards. B. 89 Conflict Between Effluent and water Quality Standards The Senate and House Committees rejected the integrated approach of water quality standards and effluent standards. Effluent st~ndards are related to available control technology and not water qualit.y stand~rds. Existing water quality standards provide a basis for enforcement only if they require a higher degree of control than that required by the new technology-based standard. There were sever.a l reasons why Congress chose not to retain water quality standards as the primary enforcement mechanism. First, many in Congress believed that the existing water quality standards were not sufficiently stringent. Second, the process of translating ambient water quality standards into meaningful effluent standards for individual point sources is both difficult and often -22- unreliable. Finally, it was believed that enforcement would be aided by a clear, uniform national standard of 90 performance. Two of the main provisions of the Act - uniform national effluent limitations based on achievable technology and enhanced water quality resulting in swimmability ("recreation in and on the water") by 1983 - are in conflict. During the first phase (ending in 1977), water quality standards assuring at least secondary contact recreation ("recreation on the water") must be converted into effluent limitations and enforced by the permit program. For this reason, such effluent limitations are referred to as "water quality derived effluent limitations." As a result of this conflict, it is thus possible that industry may be required to install something more than "best available technology economically achievable" in order to meet watezquality standards reflecting secondary contact uses. Moreover, these water quality derived effluent limitations must be achieved by 1977, regardless of economic 91 and social costs. 92 Section 1313 of the Act provides the criteria for these water quali~y derived effluent limitations. This section requires completion of standards for interstate waters, waters, 93 94 extends water quality standards to intrastate establishes procedures for the periodic review and revision of standards, 95 and requires a continuing water quality planning process in each state. 96 water quality standards developed pursuant to Section 1313 "shall be such as to protect the public health or welfare, enhance the -23- quality of water, and serve the. purpos~s of this Act. Such standards shall be established taking into consideration their use and value for public water supplies, propogation of fish and wildlife, recreational purposes, and also taking into consideration their use and value for navigation. ,,97 One of the most confusing aspects of the Act is the relationship of the water quality standards, which appear to adopt the "desired use" concept, to the swimmability goal and the uniform effluent limitations. 98 It is necessary to recognize that economic, social, and technological factors are irrelevant to the Section 1313 process. Under Section 1312, however, the imposition of water quality related effluent limitations must be preceded by a consideration of economic, social, and ' 1 conSl'd eratlons. ' 99 tec h no 1 oglca The requirement that water quality derived effluent limitations must be achieved by 1977 regardless of economic and social costs could resul·t in: several undesirable effects: (1) plant closures or production cutbacks in heavily industrialized areas, (2) the relocation of industry from water quality limited areas to effluent limited areas and the consequent degradation of relatively clean water, (3) the incautious use of experimental technology which may have adverse effects on the environment, and (4) an adverse public reaction to the Act. c. 100 No Discharge Policy The 1985 no discharge policy has been criticized by many. It is argued that an oversimplified solution such as -24- zero discharge can be expected to have at least two results. FIrst, it would be inefficient and divert scarce resources from other needs. 101 Second, the aspect of overpromise will cause an adverse reaction or "environmental backlash" which may be detrimental to the environmental cleanup effort when the 1985 goal is unfulfilled. l02 The National Water Commission criticizes Congress on both grounds: [T]he no discharge policy holds out a promise of clean water which it cannot redeem. Water quality regulation which loses touch with the reasons people value water is hopelessly adrift and eventually will flounder. When it does, the attendant dashing of public expectation will make it more difficult to marshall public support to reestablish a program with rational objectives. l03 A less critical view of the no discharge policy views Congress as having taken both an innovative and at the same time a protective step. first time ~ ~ongress It is innovative because for the has stated that the n~tion's waters are . 104 no 1 onger ava1'I a bl e f or waste d'1sposa 1 purposes. ' It 1S protective in that the lack of knowledge of the potentially permanent effects of pollution over a period of time requires an adequate margin of safety, which the stringent requirements of the Act provide. Over a period of time small amounts of many .pollutants may attain toxic levels. Since no one knows when that limit is reached, the most conservative approach , f urt h er 1ntro ' d uct10n ' restra1ns 0 f as many wastes as POSS1' bl e. 105 It should be noted that this no discharge policy is not itself a regulatory requirement of the Act~060ther than those relating to toxic pollutants, all of the provisions -25- establishing effluent restrictions contain provisions / which avoid undue economic hardship. However, the no discharge policy does have an important purpose in the Act. It reflects the 'strong congressional sentiment that no industry or municipality has a right to use the nation's waters to discharge its wastes, that pollution continues only because of technological limitations, and that a major research and development effort should be undertaken aimed at bringing no discharge technology within the , economlC capa b"lllty 0 f ' d ustry. 107 every ln IV. Permit System The permit system is the most useful regulatory device in any water pollution control program. Under such a system, all those who seek to discharge pollutants must obtain a permit in advance. Regular monitoring is required, and a report of the discharge strength and volume is made to the permitting agency. In the area of permit issuance, the Act attempts to utilize the state experience with water quality control activi ties ~ by _requi;t:i ng :the :-EPA:-to -- draw upon those-'- experiences . Most states for many years have had permit systems similar to the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) created by the 1972 Amendments. The Act, therefore, is actually instituting a new national permit system and not necessarily a new method of pollution control. l08 -26- A. Defining "Navigability" The NPDES is nothing more than a discharge permit system that employs the concept of navigable waters as the jurisdictional basis of its regulatory scheme. The 1972 Act defines "navigable waters" to mean "waters of the United States, including territorial seas" and limits the applicability of the permit program to the "discharge of pollutant, or combination of pollutants." "Discharge of pollutant" is defined as "the addition of any pollutant to navigable waters from any point source." NPDES is thus applicable only to those who discharge pollutants- from point sources into waters of the United States. The meaning of the term "waters of the United States" must first be established, however, before it is possible to determine the e x tent of its jurisdictional limitation. One term the [House] Committee was reluctant to define was the terril "navigable waters." The reluctance was based on the fear that any interpretation would be read narrowly. However, this is not the Committee's intent. The Committee full y intends that the term "navigable waters" be given the broadest constitutional interpretation unencumbered by agency determinations which have been made or may be made for administrative purposes.10 9 This statement of the House Committee raises several problems. The Committee desired the "broadest possible constitutional interpretation" of the term "navigable waters," yet a short review of the relevant cases would have revealed that the definition selected by the Committee was clearly restricted to waters that are -navigable in fact, historically navigable, : or those that can reasonably be made navigable. -27- The Committee report clearly indicates that past or future agency determinations should not "encumber" its definition. Yet, if Congress had intended the 1972 Act to apply to all discharges regardless of the traditional classification of the receiving water as navigable or not, they should have realized that the courts had already limited the definition of "navigable waters.,,110 The EPA interprets "navigable waters" to include not only interstate waters and the traditional navigable waters but also intrastate waters which are either used by interstate travelers for recreational purposes, from which fish are taken and sold in interstate commerce, or which are utilized by industries engaged in interstate commerce. Therefore, one looks not only to the water, but in the case of intrastate waters, one must also look to the person -who is discharging in order to determine whether the receiving water is . bl e. 111 navJ..ga B. Navigability and the Commerce Clause The question then remains whether the term "navigable waters" may be reasonably construed to be coextensive with the commerce clause. If the legislation requir.es control of pollution by those whose activities "affect interstate commerce;" a company polluting a non-navigable water could be required to meet the standards of the statute. An act prohibiting pollution which affects commerce would therefore form a broader basis for controlling discharges than a statute prohibiting only discharges into navigable waters. While the power of Congress to regulate navigable waters is not expressly granted in the Constitution, the ability to -28- control navigable waters is derived from the broad powers granted under the commerce clause. 112 However, even if the broad coverages under the 1972 Amendments are ruled to be an invalid extension of congressional powers, it has been suggested that by making the large federal water pollution grants to the states conditional upon conformity with federal standards, " " an 1n d'1rect manner. 113 Congress may ac h 1eve 1tS goals 1n If federal regulatory authority under the Act is limited to navigable waters, a major practical problem arises in the determination of whether a given water- body is a navigable water. Application of the traditional tests is difficult without a prior judicial decision, since the point at which a non-navigable water becomes navigable ' ' 114 1S no t easy to d eterm1ne~ The first case to meet the jurisdictional issue of navigabilit~~as United States v. Holland,llS which held that federaljurisdicti~n constit~tionally extends to all waters of the United States affected by interstate commerce without regard to their navigability, and therefore, the defendant's fill activity required a permit under the Act. Conc~rning the constitutional question of whether Congress can extend its control beyond navigable waters, the court held that the exercise of congressional power over water resources is constitutional regardless of the navigability ' 1 ve d . 116 o f t h e water 1nvo ' T h e court f oun d th a t expans1ve interpretations of the commerce clause require only a "reasonable relation to, or effect on, interstate commerce" . -29- through any activity regulated ' by Congress. 117 water pollution, the court stated, obviously affects interstate commerce, and therefore dredging and filling may be regulated as a polluti~n creating activity. To hold that only pollution in navigable waters could affect interstate commerce, the court declared, "would be contrary to reason." 118 Consideration of the second question, whether Congress intended to extend federal jurisduction beyond navigable waters, is complicated by the use of the term "navigable waters" in the Act. Finding "verbal acrobatics"necessary to determine . 119 the clear meaning of the statute, the court turned to an ex amination of the legislative history of the Act. The scope of the Act was originally restricted to navigable waters, but the definition "waters of the United States" was substituted with ' the expressed intention of broadening the Act's jurisdiction. This indicated to the court that , d e d to e 1"lmlnate t h e navlga ' b 1' I 'lty restrlc , t, 'lons. 120 Congress lnten '- Although the Holland court properly concluded that Congress had . the power to go beyond the navigability limitations in its control over water pollution, the fact remains that Congress did not do this. The Act is directly related to the concept of navigability. authority to base its regulatory scheme clause, but it failed to do so. Congress had the u~on the commerce Such e x press legislative , ' d e d . 121 actlon s h ou Id not b e d lsregar It is doubtful that most courts are willing to alter the e x press statutory language to bring dischargers into non-navigable waters within the Act. Although this was done -30- in Holland, the reasoning applied is suspect. Rather than attempting to read navigability out of the Act, courts should, when presented with the issue, determine the receiving water's navigability in each case. If the water is found to be non-navigable under the traditional tests, the court should not employ "verbal acrobatics" to bring the case within the Act. 122 C. Enforcement The 1972 Amendments provide prompt and effective enforcement procedures to replace enforcement conferences and ISO-day notices that were required under the Water Quality Act of 1965. 123 Under the 1972 Act a violation occurs whenever there has been a discharge of pollutants. Provisions for federal enforcement are contained in Section 1319 of the Act. Manufacturers are required to monitor discharges at point sources and to keep records of the results of . ~ollution abatement. The EPA or the state is authorized to inspect these books and records to determine ' . 1 ate d . 124 · be1ng wh et h er or not t h e Act 1S V10 It is possible that the recordkeeping requirements and inspection provisions under the 1972 Amendments will lead to results that have occurred under similar sections of other environmental legislation. The costs of fulfilling statutory bookkeeping requirements are often prohibitive. Furthermore, provisions that limit inspections to a ?earch for violations also limit the constructive assistance that might otherwise be available from the regulatory agency, since wrongdoers then attempt to conceal violations rather -31- than correct them. In order for the enforcement of the 1972 Amendments to be effective in terms of restoring the integrity of the nation's waters, the EPA and the states must be certain that the regulatory procedures are used primarily to prevent and remove water pollution rather than punish the slightest violation. 125 The self-disclosure and penalty provisions are an important mechanism in the enforcement of the Act. Section 1321(b) (5)126 of the Act requires any person in charge of a vessel, onshore facility, or offshore facility to notify the appropriate United States'.·'government agency immediately after acquiring knowledge of any harmful discharge of oil or other hazardous substances. Failure to notify may subject the offender to criminal penalties of imprisonment up to one year, a fine of up to $lD,OOO, or both. The Act further provides that: NQtification received subject to this paragraph or information obtained by the e~plo~tation of such notification shall not be used against any such person in any criminal case, except a prosecution for perjury or for giving a false statement. 127 Section 1321(b) (6)1?8 also provides that any owner or operator of a vessel or facility from which .a pollutant is discharged "shall be assesed a civil penalty" of not more than $5,000 for each offense. The civil penalty in Section (b) (6) may be compromised. In determining the amount of the penalty or the compromise, the Administrator may consider the appropriateness of the penalty to the size of the firm charged, the effect on the -32- operator's ability to continu~ gravity of the violation. provided. in business, and the No defenses, however, are Thus, even though the discharge may have been caused by an act of God, act of war, negligence on the part of the government, or an act or omission of a third party, the operator may still be liable. This provision is being contested as contrary to due process and equal protection ' h t s. 129 rlg It has also been urged that if the penalty specified in Section (b) (6) may be characterized as criminal, and if the self-disclosure mandated by Section (b) (5) furnished the basis for the imposition of the penalty, then the Act mandates a violation of the constitutional privilege against self-incrimination. In that situation, the two sections could coexist only if the immunity provided in (b) (5) were extended to the (b) (6) penalty. Hence, the proper legal characteriz~tion of that penalty is of primary importance. 130 It is difficult to perceive a :funct'ion ,of J b) :( 6") :6ther than to punish persons responsible for discharges of pollutants. There are no regulatory aspects in the section, and the provision relating the amount of the penalty to the size of the violator's business and his ability to stay in business is without logical relationship to the expenses resulting from the discharge. Thus, both the legislative history and the wording of the Act favor a determination that Section (b) (6) imposes a criminal penalty. In substance, the cases 132 131 appear to mandate the application of fifth amendment self-incrimination protection -33- to proceedings for the collection of penalties, even though such proceedings are civil in form and are civil regarding the application of other constitutional safeguards. \ However, this self-incrimination protection may not be available if the penalty assessed has purely remedial functions. It is well settled, then, that immunity must be afforded when requirements, such as statutory self-reporting provisions, could lead to the imposition of punitive . 133 sanctlons. 134 Q One court further pointed to the compulsary character of the penalty as inconsistent with a remedial purpose and indicated that no legitimate governmental purpose other than the punishment of violators could be attributed to the penalty. The connection between the mandatory self-disclosure provision and th~ penalty provision was characte~ized as a "backdoor procedure" for avoiding the statutory guarantees of 135 . . lmmunl ty, . · The opinion went on to observe that the government's position, if supported, must lead to a frustration of the statute's purpose. Offenders would be encouraged to disclose a discharge when the chances of detection were very small, while conscientious operators would incur the monetary penalty. Therefore, major spills can be detected more easily, and offenders will be more likely to report them through fear of criminal sanctions; however, the $5,000 civil penalty will, in these instances, probably have little significance by comparison with the considerable cleanup costs.1 36 -34- D. Federal-State Relations The federal government's position in controlling the nation's water resources has been consistently enlarged and rarely limited. Thus, 'when a specific problem has needed a specific answer, the federal government itself has dealt with water pollution by legislation as well as by executive order. The federal government has been somewhat ambivalent with regard to intergovernmental relationships. For example, in the Water Quality Act of 1965 the federal government, while apparently determined to relinquish water pollution control to the states, in reality created a more meaningful federal role. 137 Ev en though the federal government is authorized to solve national problems on a region-by-region basis, it is not designed to do so. While the government attempts to meet urgent regional needs on an individual program basis, it cannot operate as a scheme of concurrent regional governments fulfilling the continuing needs of citizens in particular geographic areas. Thus, the nation is now undergoing an era of the new federalism, which includes expanded federal incentives to states to solve state and . 1 pro bl ems. 138 reglona The 1972 Act gives clear direction that states with acceptable programs need not submit to an EPA-administered program, while the EPA has indicated a desire to have as many state-approved programs as possible so that routine decisions and permit issuance will largely be the responsibility of the states. 139 Since the new permit program applies only -35- to surface waters, state programs already in existence will continue to regulate discharges to land, as well as " h arges f rom non-polnt " d lSC sources. 140 The Act, furthermore, provides for both public and 141 adjudicatory hearings. The aspect of public participation is important in the whole scheme of water pollution . as expressed in the Act. 142 The states have adopted various methods in attempting " " " f actory water con d"" to a 11 eVlate preval"1 lng unsatls ltlons. 143 However, the results of state efforts have been a great deal of fragmentation and uncoordinated effort. For example, in most states more than one agency (as many as six} : are involved. This situation is primarily due to the divergence of states' administrative and legislative approaches to water pollution control. While such division of authority is not necessarily inefficient, it does indicate ad hoc development rather than the formation of agencies which are ~ 144 desig~ed to fit appropriate problems. During the past twenty years, states have attempted to correct those policies which proved ineffective. Single, special agencies were formulated to deal solely , 145 with the pollution problem in all its aspects. More recent state statutes authorize the appropriate administrative agency to develop a comprehensive program in order to deal with water pollution. Furthermore, recent state acts are generally designed to give the applicable agency broad discretion in administration of the program and to make the agency's jurisdiction complete over all state waters. 146 -36- V. Recommendations The 1972 Amendments have brought notable increases in the quality of water'throughout the country, but improvements in some of the provisions would add greatly to the effectiveness of the Act. adequately with point While the Act deals ~ources~the non-point source problem accounts for substantial c3.IDountsof discharges, so that immediate attention must focus on the development of enforcement guidelines for these wastes. 147 The Amendments also create the situation in which industry may be required to install something more than "best available technology economica"lly achievable" in order to meet water quality standards reflecting secondary contact uses. The ~better than best" problem should be resolved by amending the Act to pursue the objectives of Section 1312, , which require standards stricter than "best " available technology economically achievable" when c3. cost-benefit analysis justifies that result. Thus, "better than best" technology would be required to meet water quality derived effluent limitations only after the preparation of a cost-benefit study. 148 Furthermore, the Act should be amended to allow for limited three year postponements of the 1977 deadline in cases where density of population and industrialization or present water conditions preclude attainment. Such a proposal would allow a more realistic approach to severe problem areas. 149 -37- Provisions that limit inspections . to a search for violations negate the constructive assistance that might otherwise be available from the regulatory agency, since violators then seem inclined to conceal violations rather than correct them. The EPA and the states must be certain that regulatory procedures are utilized primarily to prevent and remove water pollution rather than punish the slightest violation. 150 On a broader basis, the framework used to analyze water pollution must be expanded. Generally, there is a need to institutionalize the relationship between water pollution and water supply. The two are undeniabl y related, especially in those areas interested in waste water reclamation and reuse. The water resource, then, must be · ·1tS ent1rety . . tl y. 151 · d1n stu d 1e 1. f 1. t ·1S t 0 b e manage d e ff·1C1en There is also a need to concentrate resources where they can have the most lasting impact. '" The first priority for pollution abatement should be the concentration towards the most severe problems. Due to the timetables in the Act, the administrative process is somewhat restricted in setting its own priorities. However, within the confines of the legislation, the strategy must be directed toward the most .. · · . 152 severe problems w1th1n areas 0 f maJor popu1 at10n concentar1on. Planning in advance is also increasingly important. In some areas where there has not been adequate planning, ~on~y is spent on new treatment facilities to' meet the legal deadlines at the same time that engineers are planning where the facilities should be located and how they should built. 153 -38- Finally~ no matter what changes are proposed, the ultimate effectiveness of any regulatory scheme is dependent upon society's consumption habits a~d how willing a society , t 1S 0 a d op t ' t er po 1"lCles regard1ng , s t r1C water use. 154 Conclusion The 1972 Amendments, providing a more thorough enforcement mechanism than previous water pollution legislation, make it clear that the nation's waters are no longer to be used for waste disposal purposes. The Act adopts a system of effluent standards as its primary regulatory' scheme, although a permit system and grants program promote the effectiveness of that scheme. are ~ The effluent standards related, not to water quality standards, but to restrictions of technological availability and economic capability. Eventually, these standards are meant to lead to a zero discharge. goal · ~f Water quality ~tandards ~--~.- have not been excluded altogether, however, and may require a "better than best" technology to meet water quality derived effluent limitations. The permit program applies to all point sources on "navigable waters," defined in the Act as "waters of the United States." Despite the holding in Holland, a navigability restriction is probably present. will then be r~quired The courts to determine, in each case, whether a particular waterbody is navigable. The enforcement of the Act, with its conflict~ng self-disclosure and penalty provisions which seem to violate self-incrimination rights, tends to promote the concealment -39- of violations. If effective enforcement is to be eventually attained, federal-state relations must be enhanced. Footnotes 133 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq. (1972). 233 U.S.C. § 1321 (1972). 333 U.S.C. § 1342 (1972). 433 U.S.C. § 1288 (1972). 5Senate Comm. on Public Works, A Legislative History of the Federal Water Pollution Control Acts of 1972, 93d : C6ng~, 1st Sess. 1460 (1973). 6 A. Kneese, The Economics of Regional Water Quality Management 40-41 (1964). 7See Crutchfield, Water and the National Welfare, 42 Wash. L. Rev. 177, 183 (1966). 8 - Schultze, Setting National Priorities 119-26 (1970). 9 Goldfarb, Better Than Best: A Crosscurrent in the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 11 Land & Water L. Rev. 1, 2-3 (1976). lO. See generally Zwick & Benstock, Water Wasteland (1971). 1111 Land 12 & 33 U.S.C. Water L. Rev. 1, 4-5 (1976). CVJI".....-:;'"\~, c..U g.~) § 1158 (1970). 13 Has k'lns, Towar d s Better Ad mlnlstratlon " , Control, 49 Ore. L. Rev. 373, 374 (1970); 0 f Wa t er Qua l 1' t y One s y stem classifies pollutants according to their instrearn assimilative properties as degradable or non-degradable. See generally A. Kneese & B. Bower, Managing Water Quality: Economics, Technology, Institutions 13-31 (1968). Most commonly used measurements of pollution are applicable only to degradable waters. Perhaps the most widespread measure of the effect of wastes on water quality is that which measures the biological oxygen demand (BOD) of the waste load. Since non-degradable wastes are not affected by biological processes, however, the BOD measurement is useless in describing certain types of wasteloads and highly inaccurate in other instances where non-degradable wastes account for a high percentage of the discharge. W. Eckenfelder, Water Quality Engineering for Practicing Engineers 10-11 (1970). 1411 Land & Water L. Rev. 1, 4-5 (1976). 16 42 u.s.c. §§ 1742 U. S . c. 538 et seq. (1946). 1 et ~ ,( 19 24) . § 1 et seq~ (1912). 18 42 u.s.c 19 33 u.s.c. § 407 et seq. 20 33 u.s.c. § 1151 et seq. (1948). 21 33 u.s.c. § 1151 et seq. (1952). 2233 u.s.c. § 1152 (1970). 24 33 u.s.c. § 1152(d) 26 u.s.c. § 1151 et seq. 33 § (1899). (1970). (1956). 27 33 u.s.c. §§ 1160 and 1151 (1970). I ':. 28 p . L . 84-660, §8, 70 Stat. 504 29 33 u.s.c. § 1171,(1970). 30 33 u.s.c. § 1158 51.:. - - - - (1956) . vJ,--'()~ U'?u ?' L. /..)c _ (1970). 31During the period of administration of the 1965 Amendments by the Department of the Interior, few 180-day notice actions were initiated for violators of water quality standards. A more vigorous enforcement program was conducted subsequent to the vesting of enforcement responsibility with the EPA in December of 1970. EPA initiated 144 actions prior to the enactment of the 1972 Amendments; however, only four of these cases resulted in actual court action by the Justice Department. u.s. Environmental Protection Agency, The First Two Years: A Review of EPA's Enforcement Program (1973). 32 . - 33 U.S ~ C. §§ 1153, 1155-1158, 1160, 1173, 1175, 431-437, and 466 (1970). 33 33 U.S.C. §§ 1151-1175 (1970). 34 33 U . ~ S.C. § 1161(b) (1) (1970). 35(1) Failure to notify of an oil spill, 33 U. S.C. §1161(b) (4) (1970), (2) Knowingly discharging oil, 33 U.S.C §1161 (b) (5) (1970), (3) Marine disaster creating a substantial pollution hazard, 33 U.S.C. § 1161(d) (1970), (4) Imminent and substantial threat to an offshore or onshore facility, 33 U.S.C. § 1161 (e) (1970), (5) Recovery of cleanup cost, 33 U.S.C. § 1161(f) (1970), and (6) Violation of removal and prevention regulations, 33 U.S,C. § 1161(j) (1970). 36 33 U.S.C. § 1254 (1972). 37 33 U.S.C. § 1251 (1972). 38 33 U.S.C. § 1256 (1972). 39 33 U.S.C. § 1365 (1972). 40Senate Comm. on Public Works, A Legislative History of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 93d Cong., 1st Sess. 1460 (1973). 41 Speth, The 1972 Federal Water Pollution Control Act: Problems and Prospects After One Year, 7 Nat. Res. L. 249, 250 (1974). 42 . McThenla, An Examination of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 30 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 195, 210 (1973). 43 . 33 U.S.C. § 1251(a) (1) (1972). 44"It is the national goal that whenever attainable, an interim goal of water quality which provides for the protection and propogation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and provides for recreation in and on the water be achieved by July 1, 1983." 33 U.S.C. § 1251(a) (2). The 1983 goal is significant in its description of two national standards of measurement. The most widely accepted measure for determining whether a stream will provide for the propogation of fish and wildlife is the amount of dissolved oxygen in the water. The recreation or "swimmable" portion of the standard is usually measured by bacteria count. 45 33 U.S.C. § 1311(b) 46 33 U.S.C. 47 48 (1972) . § 1311 (b) (1) (A) (1972) . 33 U.S.C. § 1311 (b) (2) (A) (1972) . 118 Congo Rec. 16870, 16873 (daily ed. Oct. 4, 1972) . 49 33 U.S.C. § 1311 (b) (1) (B) (1972) . 5°33 U.S.C. § 1311 (b) (2) (B) (1972) . 51 33 U.S.C. § 1313 (1972) . 5211 Congo Rec. 16873 (daily ed. Oct. 4, 1972). 53 " 33 U.S.C. § 1342 54 (1972). 33 U.S.C. § 1342(b) (1972). 55 33 U.S.C. § 1319 (1972). 56 . Sectlons 1311 (general effluent limitations), 1312 (water quality related effluent limitations), 1316 (standards of performan,ce for new sources), 1317 (toxic substances), and the permit system of Section 1342. 57 59 33 U.S.C. § 1319 (a) (1) (1972). 33 U.S.C. § 1319 (a) (3) and § 1319(b) (1972) . 6°33 U.S.C. § 1319 (c) (1) and § 1342 (b) (7) 61 62 63 64 (1972) . 33 U.S.C. § 1281 (1972) . 33 U.S.C. § 1288(a) and § 1284(a) 33 U.S.C. §1284 (b) (1) 33 U.S.C. §1317 (b) (1972) . (1972) . (1972) . 65 66 67 68 33 U.S.C. § 1319 (a) (1972) . 33 U.S.C. § 1284 (1972) . 33 U.S.C. § 1342 (b) (1972) . The Act also refers to non-point sources. issue, however, the legislation is incomplete. On this However, because the full nature of the problem is not yet known and because of the lack of knowledge concerning alternative measures, a national legislative program seems unwise at the present time. 30 Wash. & Lee 19:;, 212-213 (1973). 69A . Kneese & B. Bower, Managing Water Quality: Economics, Technology, Institutions 41 (1968). 70Section 1314(b) directs the Administrator to consider "process" changes in determining what is the "best practicable control technology currently available" and the "best available technology economically achievable." 33 U.S.C. §" 1314 (b) (1) (B), See~' (2) (B) (1972). 71Note ,10 Harv. J. Legis. 565, 574-75 (1973). 72 The House and Senate conferees both desired uniformity: The conferees agreed upon this limited cost-benefit analysis in order to maintain uniformity within a class and category of point sources subject to effluent limitations, and to avoid imposing on the Administrator any requirement to consider the location of sources within a category or to ascertain water quality impact of effluent controls, or to determine the economic impact of controls on any individual plant in a single community. 118 Congo Rec. 16873 (daily ed., Oct. 4, 1973) 73 Katz, The Function of Tort Liability in Technology Assessment, 38 Cin. L. Rev. 587, 634 (1969J. 74 10 Harv. J. Legis. 565, 576-77 (1973) .\.,J~ C"-'---:t. J5 Id . at 589. 76 Id . at 590. 77 The EPA's discretion in determining what level of control is "practicable" or "economically achievable" is substantial. Consequently, the amount of reduction actually achieved and the amount of economic dislocation accepted as tolerable are likely to be determined more by the political process and public opinion than by the wording of the <.::LA::- a:f statutory standards. 10 Harv. J. Legis. 565, 580 (1973). 78 10 Harv. J. Legis. 565, 578 (1973). 79 The EPA has conceded that although most businesses will be capable of cost recovery, older plants and those plants lacking the land required for treatment facilities will close rather than attempt to meet the standards. The EPA's conclusion was that plant closings are expected in almost all industries. 4 BNA Environ. Rep. Current Dev. 1584-85 (1974). 80· 10 Harv. J. Legis. 565, 579 (1973). 8IsEction 1314(b) (1) (B) lists seven factors relevant to the determination of "best practicable control technology currently available." These factors "shall include consideration of the total cost of application of technology in relation to the effluent reduction benefits to be achieved from such application, and shall also take into account the age of equipment and facilities involved, the process employed, the engineering aspects of the application of various types of control techniques, process changes, non-water quality environmental impact (including energy , requirements), and such other factors as the Administrator deems appropriate." 33 U.S.C. § 1314 (b) (1) (B) (1972). 82 Comment, 10 Gonzaga L. Rev. 165, 169 (1974). 83 10 Harv. J. Legis. 565, 584 (1973). 84 See Hearings on H.R. 11896, H.R. 11895 Before the House Comm. on Public Works, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 259 (1971). 85calculating accurately the marginal benefits of moving from 90 to 95 per cent reduction would require calculation of the benefits derived from present control levels (assuming this is possible) followed by a computation of the expected benefits from applying the best practicable technology (an even more uncertain task). must then b~ The difference in these two figures compared with the marginal cost of changing from present control levels to best practicable control technology. A reasonably empirical calculation of this type is beyond the scope of current cost-benefit theory. A. Kneese & B. Bower, Managing Water Quality: Economics, Technology, Institutions 129 (1968). 8~section1367(e) requires the Administrator to "conduct continuing evaluations of potential loss or shifts of employment which may result from the issuance of any effluent limitation or order under this title, including threatened plant closures or reductions in employment allegedly resulting from such limitation or order." that "nothing in this subs~~n Although the section provides shall be construed to require or authorize the Administrator to modify or withdraw any " effluent limitation or order issued under this title," the practical effects will be to pressure the Administrator to minimize economic dislocation whenever possible. § 1367 (e) 33 u.s.c. (1972). 87 The Act does provide, however, that point sources which corne ~nto existence before 1983 will not be subject to more stringent standards of performance for a ten year period beginning on the date of completion of such construction, or during the period of amortization, whichever is longer. 10 Gonzaga L. Rev. 165, 170 88 (1974). 10 Gonzaga L. Rev. 165, 174-75 (1974) 89 . ~L rd. at lilO. : 90 1 IriH arv. J. Legis. 565, 571-72 (1973).W/~ 91 11 Land & Water L. Rev. 1, 21 (1976) .UJ~ ~233 93 94 95 96 97 98 u. S';c. § 1313 (1972) . 33 U.S.C~ § 1313 (a) (1) 33 u.s.c. § 1313 (a) (2) , (3) 33 u.s.c. § 1313(c) (1972) . 33 u.s.c. §: 1313 (e) (1972) . 33 u.s.c. § 1313 (e) (2) (1972) . (1972) . (1972) . 11 Land & Water L. Rev. 1, 12 (1976) . 99rd~ at 13, 15. 100 rd . at 21. 101" Ad optlon . 0 f a no d lse . h argeI po·ley arnoun t s t 0 th e imputation of an extravagant social value to an abstract .' concept of water purity; a value the Commission is convinced the American people would not endorse if the associated costs were fully apppreciated and the policy alternatives clearly understood." Review Draft - Proposed Report of the National Water Commission 4-5 (1972). 102 30 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 195, 208-09 (1973). 103 . Review Draft- Proposed Report of the National Water Commission 4-6 (1972). 104 . Senator Muskie, the principal draftsman of the Act, emphasized the strictness of this policy: "The use of any river, lake, stream, or ocean as a waste treatment system is unacceptable." 117 Congo Rec. 17397 (daily ed., Nov. 2, 1971) . 105 30 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 195, 209 (1973). 106 Senator Mus k le,ln " d th a t comp 1 ete can d or, d ec Iare "the 1985 " deadlin~ fo~ is a policy objective. is not enforceable." achieving no-discharge of pollutants It is not locked in concrete. It 117 Congo Rec. 17397 (dailyed., Nov. 2, 1971). 107 7 Nat. Res. L. 249, 250-51 (1974). 108 · , The Federal Water Pollution Control Act and the ROle, b States: Love in Bloom or Marriage on the Rocks, 7 Nat. Res. L. 231 (1974). ~P9H.R. Rep. No. 911, 92d Cong., 2d Sess. 131 (1972). llO. Comment, 1 9 St. ' LOU1S L. J 208 ., 213 (1974) . 1117 Nat. Res. L. 231, 232-33 (1974). 112 19 St. Louis L. J. 208, 213 (1974). 113Neill, The Water P;llution Control Act of ~972: Federal Jurisdiction, 29 J. Mo. B. 402, 405 (1973). 114 19 St. Louis L. J. 208, 220 (1974). 115 373 F. Supp. 665 (M.D. Fla. 1974). 116 Id . at 673. 119 Id . at 671. 120 Id . at 672. 121 19 St. Louis L.J. 208, 219 (1974). 122 Id . at 221. 123 "House Co'mm. on Public Works, Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, H.R. Rep. No. 911, 92d Cong., 2~ Sess. 114 (1972). 124 33 U.S.C. §1318 (1972). 125stern & Mazze. Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972, 12 Am. Bus. L. J. 81, 85 (1974). 12 6 33 U. S . C. § 13 21 (b) (5) ( 19 7 2) . 128 33 U.S.C. § 1321(b) (6) (1972). 12 9Al. tk lns, . . . t 7 Nat . Re s L . 241 In d ustry Vlewpoln, . , 24 3 ( 1974 ) . 130cornment, 49 Tul. L. Rev. " 1124, 1,1 25 (1975). 131 Id . at 1129-30. 132United States v. ,United States Coin & Currency, 401 U.S. 715 (1971); Lees v. United States, 150 U.S. 476 (1893); Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616 (1886). 133 See, e.g. Leary v. United States~ 395 U.S. 6 (1969); Haynes v. United States, 390 U.S. 85 (1968); But cf. California v. Byers, 402 U.S. 424 (1971). 134United States v. LeBeouf Brothers Towing Co., 377 F. Supp. 558 (E.D. La. 1974). 135 Id . at 565. 136 Id . at 564. 137 Kl lne, " Intergovernmental Relations in the Control of water Pollution, 4 Nat. Res.L. 505, 506-507 (1971). 138Hart " ,creative Federalism: Recent Trends in Regional Water Resources Planning and Development, 39 U. Colo. L. Rev. 29 (1966). 139 7 Nat. Res. L. '231, 232 (1974). 140 Id . at 233. 141See generally Romanek, Federal Viewpoint, 7 Nat. Res. L. 225 (1974). 142 7 Nat. Res. L. 225, 227 (1974). 143 T h ede f"" " " state programs wh"lC h genera 11 y lClenCles ln required reversals were: (1) inadequate statutory authority, (2) lack of forceful administrative control, (3) inappropriatenes of public health dominion over program implementation, and / (4) lack of any centralized authority. Hines, Nor Any Drop to Drink: Public Regulation of Water Quality - Part I: State Pollution Control ' Programs, 52 Iowa L. Rev. 186, 204 (1966) . 144 . 4 Nat. Res. L. 505, 510-11 (1971). 145 . . Glndler, Water Pollution and Quality Controls §227.4 (Clark ed., Waters and Water Rights, vol. 3, 1967). l46 4 Nat. Res. L. 505, 510-11 (1971). 147] Nat. Res. L. 225 (11974). 148 11 Land & Water L. Rev. 1, 21 (1976). 149 Id . at 22. 15012 Am. Bus. L.J. 81, 85 (1974). 151 7 Nat. Res. L. 231, 237 (1974). 152 153 154 30 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 195, 219-20 (1973). 7 Nat. Res.L. 231, 238 (1974). 30 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 195, 213 (1973).