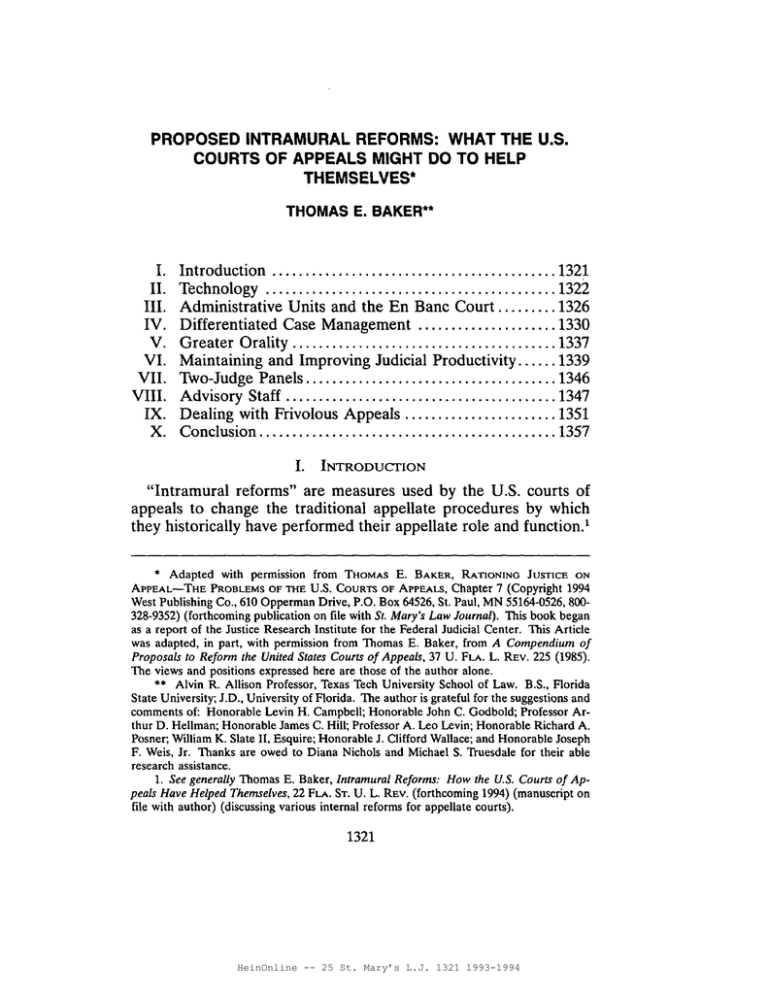

I. Introduction 1321 II. Technology 1322

advertisement